Robert Greene (dramatist)

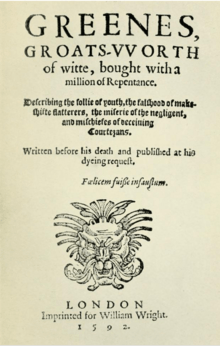

Robert Greene (1558–1592) was an English author popular in his day, and now best known for a posthumous pamphlet attributed to him, Greene's Groats-Worth of Witte, bought with a million of Repentance, widely believed to contain an attack on William Shakespeare. Robert Greene was a popular Elizabethan dramatist and pamphleteer known for his negative critiques of his colleagues. He is said to have been born in Norwich.[1] He attended Cambridge, receiving a BA in 1580, and an M.A. in 1583 before moving to London, where he arguably became the first professional author in England. Greene was prolific and published in many genres including romances, plays and autobiography.

Robert Greene | |

|---|---|

Woodcut of Greene "suted in deaths livery", from John Dickenson's Greene in conceipt (1598) | |

| Born | Tombland, Norwich |

| Baptised | 11 July 1558 St George's Church |

| Died | 3 September 1592 (aged 34) London |

| Nationality | English |

| Occupation | Writer, dramatist, playwright |

Family

According to Richardson, "The chief problem in compiling a biography of Robert Greene is the name. Robert must have been almost the most popular Elizabethan Christian name and Greene is no unusual surname".[2] Newcomb[1] states that Robert Greene

was probably the Robert Greene, son of Robert Greene, baptized on 11 July 1558 at St George's, Tombland, Norwich. Greene later described himself as from Norwich on his title-pages, and the year is appropriate for the Robert Greene who matriculated at St John's College, Cambridge, as a sizar on 26 November 1575. The author's father was probably one of two Robert Greenes found later in parish records: either a saddler who lived modestly in the parish until 1599, or a cordwainer who kept an inn in Norwich from the late 1570s until his death in 1591. The saddler appeals to biographers who attribute the writer's later low-life sympathies to a humble birth; the innkeeper, a more prosperous man possibly related to landowners, interests scholars who note the social ambitions of Greene's early works. However, in his will proved in 1591, the innkeeper did not mention a son Robert, although he may have disinherited that son (as the writer implied in one autobiographical statement).

Both the Norwich cordwainer-turned-innkeeper and the Norwich saddler left wills, proved in 1591 and 1596 respectively, but neither will mentions a son named Robert.[3]

Career

Greene is thought to have attended the Norwich Grammar School, although this cannot be confirmed as enrolment documents for the relevant years are lost.[1] Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, provided scholarships for students from the Norwich grammar school, and for this reason Greene's matriculation as a sizar at St John's College, Cambridge, has been considered "strange".[4][1][5] A reason offered for Greene's enrolment at St John's is that some of the gentry of South Yorkshire attended St John's, and among the dedicatees of, or authors of commendatory verses for Greene's books were members of the Darcy, Portington, Lee, Stapleton, and Rogers families, all centred at Snaith, Yorkshire; according to Richardson, the Robert Greene from Norwich who was an innkeeper may have been an immigrant from Yorkshire connected to 'a large family of Greenes' who lived in the parish of Snaith, and may actually have left Norwich to reside at Snaith from 1571 to 1577.[6][1]

There is no record of Greene's having taken part in the dramatic productions at Cambridge in 1579 and 1580, although 18 of his classmates and Fellows of the Cambridge colleges acted in Hymenaeus, and 46 in Richardus Tertius.[7][8] His academic performance as an undergraduate at Cambridge was mediocre; on 22 January 1580 he took his BA, graduating 38th out of 41 students in his college, and 115th out of the total university graduating class that year of 205 students.[1][9] He "apparently transferred to Clare College for his 1583 MA", where he placed 5th out of 12 students in his college, and 29th of the 129 students at the university.[1][9][10] It was "rare for a student to migrate to another college (as Greene did) after he had received the baccalaureate",[11] and no record of Greene's transfer to Clare College has been discovered, nor does his name appear in the Clare Hall Buttery Book for 1580–84.[9] Greene's claim to association with Clare College is found in the second part of Mamillia, which was not published until 1593, after Greene's death, in which the dedicatory epistle to Robert Lee and Roger Portington is signed "Robert Greene. From my Studie in Clarehall the vii. Of Julie".[1][12]

According to Newcomb, "Other events of [Greene's] youth must be derived from autobiographical remarks that may not be reliable".[1] In The Repentance of Robert Greene, written in the first person, Greene claimed to have travelled to Italy and Spain; however, no evidence of Greene's continental trip has been found, "or—unless we take merely his word for it—that he ever made the trip at all".[9] Further doubt is cast on Greene's continental journey by Norbert Bolz, who after undertaking a computer analysis of the vocabulary of The Repentance, concluded that "The Repentance of Robert Greene was in fact not written by Robert Greene".[13]

In The Repentance, Greene claimed to have married a gentleman's daughter, whom he abandoned after having had a child by her and spent her dowry, after which she went to Lincolnshire, and he to London.[1] In Four Letters (1592), Gabriel Harvey prints a letter allegedly written by Greene to his wife in which he addresses her as "Doll". However, "[E]xtensive searches of London and Norwich records by successive biographers have failed finally to locate the record of Greene's marriage".[14]

After his move to London, Greene published over twenty-five works in prose in a variety of genres, becoming "England's first celebrity author".[1]

In 1588, he was granted an MA from Oxford University, "almost certainly a courtesy degree".[1] Thereafter the title pages of some of his published works bore the phrase Utruisq. Academiae in Artibus Magister', "Master of Arts in both Universities".[1]

Greene died 3 September 1592,[15][16] (aged 34 if he was the Robert Greene baptised in 1558). His death and burial were announced by Gabriel Harvey in a letter to Christopher Bird of Saffron Walden dated 5 September, first published as a "butterfly pamphlet" about 8 September, and later expanded as Four Letters and Certain Sonnets, entered in the Stationers' Register on 4 December 1592.[17][18] Harvey attributed Greene's demise to "a surfeit of pickle herring and Rhenish wine",[19] and claimed he had been buried in "the new churchyard near Bedlam" on 4 September.[1][20] No record of Greene's burial has been found.

According to The Repentance of Robert Greene, Greene is alleged to have written Groatsworth during the month prior to his death, including in it a letter to his wife asking her to forgive him and stating that he was sending their son to her. No record of Greene's son by his wife has been found; however, in Four Letters, Gabriel Harvey claimed that Greene kept a mistress, Em, the sister of a criminal known as "Cutting Ball" hanged at Tyburn. Harvey described her as "a sorry ragged quean of whom [Greene] had his base son Infortunatus Greene". According to Newcomb, a Fortunatus Greene was buried at Shoreditch on 12 August 1593, "whose folk-tale name might lie behind Harvey's jest".[1]

Writing

According to Newcomb, '[Greene's] works evince an inexhaustible linguistic facility, grounded in wide (if not painstaking) reading in the classics, and extra-curricular reading in the modern continental languages'.[1] He wrote prolifically: From 1583 to 1592, he published more than twenty-five works in prose, becoming one of the first authors in England to support himself with his pen in an age when professional authorship was virtually unknown.

Greene's literary career began with the publication of a long romance, Mamillia, entered in the Stationers' Register on 3 October 1580.[1] Greene's romances were written in a highly wrought style which reached its highest level in Pandosto (1588) and Menaphon (1589). Short poems and songs incorporated in some of the romances attest to his ability as a lyric poet. One song from Menaphon, Weep not my wanton, smile upon my knee, (a mother's lullaby to her baby son), enjoyed immense success, and is now probably his best-known work.[21]

In his later "coney-catching" pamphlets, Greene fashioned himself into a well-known public figure, telling colourful inside stories of rakes and rascals duping young gentlemen and solid citizens out of their hard-earned money. These stories, told from the perspective of a repentant former rascal, have been considered autobiographical, and have been thought to incorporate many facts of Greene's own life thinly veiled as fiction: his early riotous living, his marriage and desertion of his wife and child for the sister of a notorious character of the London underworld, his dealings with players, and his success in the production of plays for them. However, according to Newcomb, in his later prose works "Greene himself built his persona around a myth of prodigal decline that cannot be taken at face value".[1] His plays earned himself the title as one of the "University Wits", including George Peele, Thomas Nashe, and Christopher Marlowe.

Richardson makes a similar argument, concluding that Greene's later works 'prejudice the examination of all the work before them', and that the prose works prior to the cony-catching and repentance pamphlets establish that 'initially at least Greene was respectable'. Richardson considers that Greene:[22]

claimed from the outset a moral or civilizing purpose in his writing. His tales repeatedly illustrate the disastrous disruptions caused in life by passion and laud the life of restraint. His views are basically conservative ... He equivocates and hesitates over the defence of the values of a conservative culture, virginity, true devotion, strict moral probity.

In addition to his prose works, Greene also wrote several plays, none of them published in his lifetime,[1] including The Scottish History of James IV, Alphonsus, and his greatest popular success, Friar Bacon and Friar Bungay, as well as Orlando Furioso, based on Ludovico Ariosto's Orlando Furioso.

In addition to the plays published under his name after his death, Greene has been proposed as the author of several other dramas, including a second part to Friar Bacon which may survive as John of Bordeaux, The Troublesome Reign of King John, George a Greene, Fair Em, A Knack to Know a Knave, Locrine, Selimus, and Edward III, and even Shakespeare's Titus Andronicus and Henry VI plays.[23][1]

Greene and Shakespeare

Greene is most familiar to Shakespeare scholars for his pamphlet Greene's Groats-Worth of Wit, which alludes to a line, "O tiger's heart wrapped in a woman's hide", found in Shakespeare's Henry VI, Part 3 (c. 1591–92):

... for there is an upstart Crow, beautified with our feathers, that with his Tygers hart wrapt in a Players hyde, supposes he is as well able to bombast out a blanke verse as the best of you: and being an absolute Johannes fac totum, is in his owne conceit the onely Shake-scene in a countrey.

Greene evidently complains of an actor who believes he can write as well as university-educated playwrights, alludes to the actor with a quotation that appears in both the True Tragedy quarto and Shakespeare's Folio version of Henry VI, Part 3, and uses the term "Shake-scene", a unique term never used before or after Greene's screed, to refer to the actor. The Oxford English Dictionary notes that it is "Of uncertain or vague meaning: used by Greene in his attack on Shakespeare."

Some scholars have hypothesized that all or part of Groatsworth was written shortly after Greene's death by Henry Chettle or another one of his fellow writers, hoping to capitalise on a lurid tale of death-bed repentance.[24][25] Hanspeter Born argues that Greene wrote the whole of Groatsworth, and that his deathbed attack on the "upstart Crow" was provoked by Shakespeare's interference with a play attributed to Greene, A Knack to Know a Knave.[26]

Greene's colourful and irresponsible character has led some, including Stephen Greenblatt, to speculate that Greene may have served as the model for Shakespeare's Falstaff. His quotation has also been used as the title for the 2016 sitcom Upstart Crow on Shakespeare's life, written by Ben Elton, its story commencing in 1592 (the year the quotation was written) and featuring Greene as a character (played by Mark Heap).[27]

Some Prose works

- Mamillia: A Mirror or Looking-glass for the Ladies of England (1583), dedicated to Lord Darcy of the North

- Mamillia: The Second Part of the Triumph of Pallas (1593), dedicated to Robert Lee and Roger Portington

- The Anatomy of Lovers' Flatteries (1584), dedicated to Mary Rogers, wife to Master Hugh Rogers of Everton[28]

- The Myrrour of Modestie (1584), dedicated to Margaret, Countess of Derby

- Arbasto; The Anatomy of Fortune (1584), dedicated to Lady Mary Talbot

- Gwydonius; The Card of Fancy (1584), dedicated to Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford

- The Debate Between Folly and Love (1584), no dedicatee[29]

- The Second Part of the Tritameron of Love (1587), no dedicatee

- Planetomachia (1585), dedicated to Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester

- An Oration or Funeral Sermon (1585), no dedicatee[30]

- Morando; The Tritameron of Love (1587), dedicated to Philip Howard, 20th Earl of Arundel

- Morando; The Second Part of the Tritameron of Love (1587), no dedicatee

- Euphues: His Censure to Philautus (1587), dedicated to Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex

- Greene's Farewell to Folly (1591), dedicated to Robert Carey, esquire

- Penelope's Web (1587?), dedicated to Margaret, Countess of Cumberland, and Anne, Countess of Warwick

- Alcida; Greene's Metamorphosis (1617), dedicated to Sir Charles Blount

- Greenes Orpharion (1599), dedicated to Robert Carey, esquire

- Pandosto (1588), dedicated to George Clifford, 3rd Earl of Cumberland

- Perimedes (1588), dedicated to Gervase Clifton, esquire

- Ciceronis Amor (1589), dedicated to Ferdinando Stanley, Lord Strange

- Menaphon (1589), dedicated to Lady Hales, wife to the late deceased Sir James Hales[31]

- The Spanish Masquerado (1589), dedicated to Hugh Offley, Sheriff of the City of London

- Greene's Mourning Garment (1590), dedicated to George Clifford, 3rd Earl of Cumberland

- Greene's Never Too Late (1590), dedicated to Thomas Burnaby, esquire

- Francesco's Fortunes, or The Second Part of Greene's Never Too Late (1590), dedicated to Thomas Burnaby, esquire

- Greene's Vision, Written at the Instant of his Death (1590?), dedicated to Nicholas Saunder of Ewell, esquire

- The Royal Exchange* (1590), dedicated to Sir John Hart, Lord Mayor of London

- A Notable Discovery of Coosnage (1591), no dedicatee

- The Second Part of Conycatching (1591), no dedicatee

- The Black Books Messenger (1592), no dedicatee

- A Disputation Between a Hee Conny-Catcher and a Shee Conny-Catcher (1592), no dedicatee

- A Groatsworth of Wit Bought with a Million of Repentance (1592), no dedicatee

- Philomela (1592), Bridget Radcliffe, Lady Fitzwalter (wife of Robert Radclyffe, 5th Earl of Sussex)

- A Quip for an Upstart Courtier (1592), Thomas Burnaby, esquire

- The Third and Last Part of Conycatching (1592), no dedicatee

Verse

- A Maiden's Dream (1591), dedicated to Lady Elizabeth Hatton, wife to Sir William Hatton[32]

Plays

- Friar Bacon and Friar Bungay (circa 1590)

- The History of Orlando Furioso (circa 1590)

- A Looking Glass for London and England (with Thomas Lodge) (circa 1590)

- The Scottish History of James the Fourth (circa 1590)

- The Comical History of Alphonsus, King of Aragon (circa 1590)

- Selimus[33] (circa 1594)

In popular culture

In the Ben Elton-written sitcom, Upstart Crow, he is portrayed by Mark Heap as being alive following the publication of Groats-Worth and a constant obstacle to Shakespeare's success.

His most famous song Weep not my wanton, smile upon my knee is a recurring motif in the historical novel The Grove of Eagles by Winston Graham.

Notes

- Newcomb 2004.

- Richardson 1980, p. 165.

- Richardson 1980, p. 166.

- Richardson 1980, p. 170.

- Parr 1962, pp. 536–7.

- Richardson 1980, pp. 160–3, 170–1.

- Parr 1962, p. 542.

- Richardson 1980, p. 175.

- Parr 1962, p. 540.

- "Greene, Robert (GRN575R)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- Parr 1962, p. 538.

- Newcomb states that 7 July was "the very date in 1583 on which Greene graduated MA from Clare College"; however according to Parr, Pruvost "mistakenly contends that the M.A. was always awarded in July", and there is no record of the time of year at which M.A. degrees were awarded in 1583, although "those of 1577–80 were awarded in March and April" (p. 540).

- Bolz 1979, pp. 66–7.

- Richardson 1980, p. 173.

- Dyce 1874, p. 57.

- Dyce appears to be the first to give the specific date of Greene's death, but cites no source.

- McKerrow I 1958, pp. 151–153.

- McKerrow II 1958, pp. 81–82, 87.

- McKerrow II 1958, p. 82.

- Hartle 2017, pp. 40–41.

- The Oxford Companion to English Literature 7th Edition Dinah Birch ed. (2009) p.634

- Richardson 1980, pp. 178–9.

- Logan and Smith, pp. 81–85.

- Schoone-Jongen 2008, pp. 21–28.

- Carroll 1994, pp. 1–31.

- Born, Hanspeter, "Why Greene was Angry at Shakespeare", Medieval and Renaissance Drama in England 25 (2012), 133–173.

- "David Mitchell to play Shakespeare in new BBC2 sitcom". RadioTimes. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- Laoutaris 2008, p. 88.

- Fleay 1891, pp. 251–2.

- Freeman 1965, pp. 378–9.

- Alwes 2004, p. 119.

- Collier 1865, pp. 328–31.

- Charry, Brinda. Robert Greene: Selimus. The Literary Encyclopedia, 25 August 2007. Retrieved 26 March 2020

References

- Bolz, Norman (1979). Habicht, Werner (ed.). "A Statistical Computer-Aided Investigation of the Authenticity of 'The Repentance of Robert Greene'". English and American Studies in German; Summaries of Theses and Monographs. Tubingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag: 66–7. Retrieved 23 August 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Carroll, D. Allen, ed. (1994). Greene's Groatsworth of Wit. Binghamton, New York: Centre for Medieval and Early Renaissance Studies. pp. 1–31. OCLC 28710470.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Collier, J. Payne (1865). A Bibliographical and Critical Account of the Rarest Books in the English Language. I. London: Joseph Lilly. pp. 328–31. Retrieved 24 August 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dyce, Alexander (1874). The Dramatic and Poetical Works of Robert Greene & George Peele. I. London: George Routledge and Sons. p. 57. Retrieved 24 August 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fleay, Frederick Gard (1891). A Biographical Chronicle of the English Drama 1559–1642. I. London: Reeves and Turner. pp. 251–2. Retrieved 24 August 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Freeman, Arthur (1965). "An Unacknowledged Work of Robert Greene". Notes and Queries. 12 (10): 378–9. doi:10.1093/nq/12-10-378. Retrieved 24 August 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hartle, Robert (2017). The New Churchyard: from Moorfields marsh to Bethlem burial ground, Brokers Row and Liverpool Street. London: Crossrail. ISBN 978-1-907586-43-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- G.R. Hibbard, ed., Three Elizabethan pamphlets by Robert Greene; Thomas Nash; Thomas Dekker (Folcroft, PA: Folcroft Library Editions, 1972).

- Laoutaris, Chris (2008). Shakespeare's Maternities. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. p. 88. ISBN 9780748624362. Retrieved 24 August 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McKerrow, Ronald B. (1958). The Works of Thomas Nashe. IV. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. pp. 151–3.

- McKerrow, Ronald B. (1958). The Works of Thomas Nashe. V. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. pp. 81–2, 87.

- Newcomb, L.H. (2004). "Greene, Robert (bap. 1558, d. 1592)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/11418. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) The first edition of this text is available at Wikisource: . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- Parr, Johnstone (1962). "Robert Greene and His Classmates at Cambridge". PMLA. 77 (5): 536–43. doi:10.2307/460403. JSTOR 460403.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Richardson, Brenda (1980). Hunter, G.K. and C.J. Rawson (ed.). "Robert Greene's Yorkshire Connections: A New Hypothesis". The Yearbook of English Studies. London: Modern Humanities Research Association. 10: 160–180. doi:10.2307/3506940. JSTOR 3506940. Retrieved 23 August 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schoone-Jongen, Terence G. (2008). Shakespeare's Companies. Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate Publishing. pp. 21–8. ISBN 9781409475132. Retrieved 24 August 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Scott-Warren, Jason (2004). "Harvey, Gabriel (1552/3–1631)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/12517. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) The first edition of this text is available at Wikisource: . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- Baskervill, Charles Read, ed. Elizabethan and Stuart Plays. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1934.

- Crupi, Charles. Robert Greene (1986) ISBN 0-8057-6905-6

- Dickenson, Thomas H. "Introduction" from The Complete Plays of Robert Greene (New Mermaid Edition, 1907)

- Greenblatt, Stephen. Will in the World (2005)

- Melnikoff, Kirk, ed.. "Robert Greene" (Ashgate, 2011)

- Melnikoff, Kirk and Edward Gieskes, eds. "Writing Robert Greene: Essays on England's First Notorious Professional Writer" (Ashgate, 2008)

- Logan, Terence P., and Denzell S. Smith, eds. The Predecessors of Shakespeare: A Survey and Bibliography of Recent Studies in English Renaissance Drama. Lincoln, NE, University of Nebraska Press, 1973.

External links

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Robert Greene |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Robert Greene (dramatist) |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Greene, Robert. |

- Works by Robert Greene at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Robert Greene at Internet Archive

- The Dramatic Works of Robert Greene (1831), vol. 1 Dyce, ed., at Internet Archive.

- The Dramatic Works of Robert Greene (1831), vol. 2 Dyce, ed., at Google Books.

- The Plays and Poems of Robert Greene (1905) vol. 1 Churton Collins ed., at the Internet Archives.

- The Plays and Poems of Robert Greene (1905) vol. 2 Churton Collins ed., at the Internet Archives.

- The Honorable History of Friar Bacon and Friar Bungay 1594 text facsimile at the Internet Archives.

- The History of Orlando Furioso Malone Society Reprint, 1907, at Internet Archive.

- The Comical History of Alphonsus, King of Aragon at Elizabethan Drama.

- Greene's Groats-Worth of Wit e-text at Ex-Classics (modern spelling).

- Pandosto online.

- Hayashi, Tetsumaro, A Textual Study of Robert Greene's Orlando Furioso with an Elizabethan Text, 1973

- The Pamphleteers by James A. Oliver ISBN 978-0-9551834-4-7 (PBK) & ISBN 978-0-9551834-5-4 (HBK)

- "Archival material relating to Robert Greene". UK National Archives.