Robert Giguère

Robert Giguère dit Despins (March 9, 1616 – August 1709) was an early pioneer in New France, one of the founders of Sainte-Anne-de-Beaupré, Quebec and the progenitor of virtually all the Giguères in North America.

Early life

Unfortunately what is known for sure about Robert Giguère's life in France is very scant. His parents were Jehan (Le Jeune) Giguère (b. abt. 1580) and Michelle Jornel. Jehan's brother, Jehan "The elder" married Michelle's sister, Marie. Jehan and Michelle had nine children of which Robert was the sixth. He was baptized in the little church in Tourouvre, in the parish of Saint Aubin on March 9, 1616. Presumably he was born either on that day or just a few days earlier.[1]

It is certain that Robert Giguère was in New France in 1651. However, according to George-Emile Giguère and others, in 1644, he was missing from French census records. Indeed, he could have arrived as early as 1642.[2]

St. Aubin de Tourouvre |

Baptismal font at St. Aubin de Tourouvre |

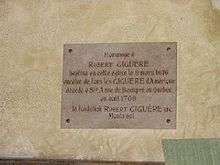

Close-up of plaque above the baptismal font |

Le Perche

Perche comes from the Latin word pertica, which means long pole and more specifically meant in old French very long trees. Hence, sylva pertica meant perche forest. It is not until the 6th century that mention is made of Perche or saltus perticus, expression denoting mountainous forest region, wild game refuge, saltus implying threshold or frontier.[3] Le Perche’ was surrounded by the following Gaulish areas and peoples: in Hyesmois country, where the Exmes people were based in Sées; in Aulerques Eburoviques country, where the Évreux people were based in Évreux; in Aulerques Cénomans country, where the Maine people were based in Le Mans; and in Carnutes country, where the Chartain people were based in Chartres.[4] Located about 100 miles (160 km) west of Paris, ancient Perche province is now located mostly in present-day Normandy région's Orne département. The County of Perche was created in 1114, when Rotrou III The Great was attributed the House of Bellême allowing control af related estates while retaining control of the Castle of Bellême.[5][4] In 1158, Bellême was conceded to Rotrou IV bringing the Rotrou dynasty to the height of its power through control of much of the old forest of Le Perche.[5] He assumed the title of Count of Perche.[4][6] Between before 1100 and 1226, three counts of Perche, Routrou III's son Rotrou IV, Geoffroy V and Thomas, consolidated the fusion of Mortagne, Bellême and Nogent lands into Perche county.[4][6] Le Perche was thereafter long granted to King of France relatives. Due to its strategic geographic and political positioning, Le Perche maintained its territorial independence to eventually be returned to the royal domain and become the ancient province bounded by Maine province to the west, Beauce/Orléanais province to the east and south, and Normandy province to the north.

In 1792, shortly after the onset of the French Revolution, France's ancient provinces were constituted into départements by the Constituent Assembly, Le Perche was carved up among four of them: Orne and Eure-et-Loir for the most part, and to a lesser extent, Sarthe and Loir-et-Cher.

As it was in the time of Robert Giguère, Le Perche has remained a beautiful pastoral area consisting mainly of gently rolling farmland, but unlike much of France, it is blessed with some beautiful forests. It also benefits from a number of rivers and streams.

Why they came

For several reasons, people left their homes in this seemingly idyllic place to begin anew in a strange place so far away. Leaving everything one has loved and known to make a very long, danger-filled journey to an unknown place so far away, could not have been easy. They were not persecuted or forced to leave, and Perche was not a poor area. The Percheron immigration movement's more than 300 people consisted of about 80 families and individuals from Perche. The King of France was offering incentives for settlers to New France including in terms of the establishment of the Company of One Hundred Associates aiming to create seigneuries in Canada's Laurentian valley, for land subdivision to qualified immigrants. Most of the Percheron immigrants settled near Quebec city. The apothecary and surgeon, Robert Giffard de Moncel, born in Perche's Autheuil hamlet near Tourouvre, was in 1634 granted Canada's first agriculture-based seigneurie situated in between Quebec city to the west and Château-Richer and L'Ange-Gardien to the east. Giffard had first come to Quebec in 1621 and had in 1634 travelled with his family as part of a first contingent of immigrants to the Giffard's Beauport seigneurie. Giffard later worked closely with the two Juchereau brothers, Jean and Noël Juchereau, who immigrated to Canada, as well as their his half brother Pierre Juchereau, all from the Tourouvre area, to recruit people to Canada. The emigrants were often hired for a period of three years, such 'engagé's being dubbed Les 36 Mois (the 36-monthers). The Percheron recruits involved a mix of skilled tradesmen and workmen consisting of both families and single individuals each engagé being paid from 40 to 120 livres per year. In addition, they were guaranteed return transportation across the ocean, subject to being granted a land concession at the end of the contract if they did not return to France.

By the time that Samuel de Champlain died in 1635, there were 132 settlers in the colony, —35 of them being Percheron. Most of the Percheron departures occurred in the three decades starting in 1634.

The Journey

Something must be said about the courage of the people who made the perilous journey from France to the New World. These poor souls were subject to all sorts of perils: weather, pirates, and illness among the crew and themselves. With so many variables, the length of the trip could vary from one month to over three. For example, it took Jean Talon 117 days to reach Quebec in 1665, but a mere 35 days for the ship, Arc-en-ciel in 1678. From a navigational perspective, it was generally better to set sail from France before May 1.

Ships of the 17th century were generally smaller than 200 tonnes (220 tons), so the accommodations on board were modest. Food would often spoil due to water seepage, and passengers had to settle for cold meals and soggy bedding. Despite all the hardships and perils, most sailors and passengers arrived safely.

The first official mention of Robert Giguère in Canada is on February 21, 1651, when he received a grant of land from Sieur Oliver le Tardif. Located in Beaupre, the grant consisted of 5 arpents (1.7 ha) fronting on the Saint Lawrence River to a depth of 1.5 leagues (7.2 km), and, in addition to the annual rent of 20 sols and 12 deniers per arpent of frontage, it required Robert to establish a residence thereon within a year. If Giguère was in a position to accept such conditions, it may be assumed that he had been already in the country for some years and was familiar with the land, the climate, and was ready to settle down. However, a 1644 census in France found him absent from the country. Although there is no official record of his life in Canada prior to 1651, some historians feel confident that he arrived in New France as early as 1642 (Robert Giguère: Le Tourouvrain 1616–1711(??), 1979).

Marriage

On July 2, 1652, in the Notre-Dame de Québec Cathedral, Robert Giguère married Aymée Miville. He was 36, and she was 17. At that time in our history, men seldom married before the age of 30; women were typically under 20. Aymee was the daughter of Pierre Miville dit Le Suisse ("The Swiss"). He was a mercenary soldier who had served in the Swiss Guards of Cardinal Richelieu. The marriage was performed by Father Joseph Poncet, and notably the ceremony was attended by Jean de Lauzon, the Governor of New France. This was indeed a great honour and an indication of the respect commanded either by Robert Giguère himself, or by his father in law, Pierre Miville.

In 1660, Jean-Baptiste, their fifth child was born. That same year, both Robert and Aymée were confirmed at Chateau Richer by Msgr. François de Laval who would be named the first bishop of Quebec, in 1674. Some have said that Jean-Baptiste was a scout in the party of men who walked from Montreal to Schenectady in February 1690, New York and burned the town down in retaliation for the Lacine massacre which occurred in 1689.

Death and legacy

Indications are that Robert Giguère was a well-respected member of the community: he had donated some land for the Basilica in Sainte-Anne-de-Beaupré, Quebec and diligently functioned as head vestryman for some time. He is regarded as a founder of Sainte-Anne-de-Beaupré, Quebec.

No death certificate was recorded for Robert Giguère, or perhaps it was lost. However, most historians agree that he died in August 1709, at the age of 93 years and 5 months. His wife, Aymée Miville followed him in death three years later, on December 10, 1712.

Robert and Aymée had 13 children, seven girls and six boys:

- Marie-Charlotte (1653–????)

- Martin (1655–????)

- Jeanne (1657–1673)

- Marie (1659–1710)

- Jean-Baptiste (1660–1750)

- Robert (1663–1711)

- Pierre (1665–????)

- Marie-Anne (1668–1762)

- Étienne (1670–1749)

- Ange (1671–????)

- Joseph (1673–1741)

- Marie-Agnès (1675–1760)

- Marguerite (1678–1723)

Five of his children were married, but only four had children. Of the boys, Joseph, Martin and Jean-Baptiste had children. Joseph and Jean-Baptiste remained in Quebec. Joseph lived out his life in Sainte-Anne-de-Beaupré, Quebec, his descendants would later move across from Quebec City to the beautiful Île d'Orléans. Jean-Baptiste settled in what is now Laprarie, Quebec and his descendants mostly come from Montreal. Martin, ultimately became the ancestor to most all Canadians who call themselves Giguère, or any the many variations of the name.

Today there are no direct descendants of Robert Giguère in Tourouvre. One of the few signs that they had been there is a spot known as La Giguerie.

They may have disappeared from Le Perche, but thanks to Robert, thousands of people, including the famous hockey player, Jean-Sébastien Giguère, who call themselves Giguère or one of its many variants, can be found all over North America.

Jean-Baptiste Giguère

Robert Giguère's son, Jean-Baptiste, may have been involved in the burning of Schenectady in 1690. He may have functioned as a scout on the raid. According to, Monseignat, governor Louis de Buade de Frontenac's secretary in his relation of the Schenectady massacre..."A Canadian named Giguère, who had gone with nine Indians to reconnoitre, now returned to say that he had been within sight of Schenectady, and had seen nobody." In his book, Un Giguère a la guerre avec Iberville Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville, Georges-Emile Giguère presents evidence that suggests that the "Giguère" mentioned was Robert's son, Jean-Baptiste. The same Jean-Baptiste may also have been among those who built Fort Detroit.[7]

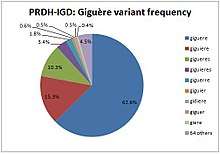

Spelling variations

There are many variations of the name "Giguère" in use today throughout North America, the most prevalent of which include, in order of importance: Giguere, Giguiere, Gigueres, Giguieres, Giguerre, Giguier, Gidiere, Giguer, Giere and 64 other variations.

According to PRDH's database for the period up to 1800, the most important dit names or nicknames associated with the Giguère name are St-Castin and Despins, with 74 and 10 instances, respectively.

Notes and references

- Our French-Canadian Ancestors, Vol. II, Thomas J. Laforest, 1984 (pp. 119–125)

- Robert Giguère : Le Tourouvrain (1616–1711??), 1979, French.

- Grégoire de Tours (6th century). Histoire ecclésiastique des Francs, cited in Centre Généalogique de l'Orne et du Perche’s (CGOP), "Le Perche existe-t-il ?"

- Centre Généalogique de l'Orne et du Perche (CGOP), Formation du Conté du Perche

- nugent.fr. A Promise of Glory - Book I France, p. 30 of 119

- Nugent.fr. Origins of the Nugent Family

- Un Giguère a la Guerre avec Iberville, Georges-Emile Giguère, 1984, French.