Ring Line (Oslo)

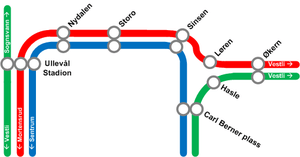

The Ring Line (Norwegian: T-baneringen or Ringbanen) is the newest rapid transit loop line of the Oslo Metro of Oslo, Norway. It connects to the Sognsvann Line in the west and the Grorud Line in the east; along with these two lines and the Common Tunnel, the Ring Line creates a loop serving both the city centre and Nordre Aker borough. The 5.0 kilometres (3.1 mi)-long line has three stations: Nydalen, Storo and Sinsen. Four-fifths of the line runs within two tunnels, with the 1.0-kilometer (0.62 mi) section between Storo and Sinsen, including both stations, being the only at-grade part. The line connects to the Grorud Line north of Carl Berners plass and with the Sognsvann Line north of Ullevål stadion.

| Ring Line | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Ring Line to the right, at Storo | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Overview | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Native name | T-baneringen | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Type | Rapid transit | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| System |  Oslo Metro | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Termini | Ullevål stadion Carl Berners plass | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stations | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operation | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | 20 August 2003 to Storo 20 August 2006 to Carl Berners plass | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owner | Sporveien | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operator(s) | Sporveien T-banen | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Technical | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Line length | 5.0 km (3.1 mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Number of tracks | Double | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrification | 750 V DC (third rail) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operating speed | 70 km/h (43 mph) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Planning for the line began in the late 1980s, and the city council approved the line 1997. Construction started in 2000; Nydalen and Storo opened on 20 August 2003, and Sinsen opened on 20 August 2006. The line cost 1,348 million kr to build and was financed through Oslo Package 2. The Ring Line is served by lines 4, 5 and 6 of the metro, operated by Sporveien T-banen on contract with the Ruter transport authority. All lines operate each fifteen minutes. Nydalen and Storo are such located that trains in either direction use the same time along the loop, effectively giving a five-minute headway to the city centre. After the opening of the line, the areas around the stations have had increased urban redevelopment. The infrastructure is owned and maintained by the municipal company Sporveien.

History

By the 1960s, Oslo had a rapid transit network that branched out north-east and north-west from the city centre. In 1987, the western and eastern network were connected, and through-trains started operating between the two networks from 1993.[1] Plans to make a second connection through the borough of Nordre Aker were launched by politicians in the 1980s. It was argued that this was cheaper than building roads, with the per-kilometre price being about a quarter of that for motorways. Some politicians also saw the Ring Line as an opportunity to close all parts of the Oslo Tramway, except the Ekeberg- and Lilleaker Line.[2] Oslo Sporveier, the contemporary operator of the metro, started planning the line during the late 1980s.[3] The plans would take advantage of the Gjøvik Line's right-of-way between Storo and Sinsen, while the section from Storo to Tåsen would have to be built in a tunnel.[4]

A projection for the line was presented in 1991 by Oslo Sporveier, where daily ridership was estimated to be 54,000 passengers. The plans included a possibility for the high-speed Gardermoen Line, that would be built to Oslo Airport, Gardermoen, to have a stop at Storo. This was later discarded when it was instead chosen to be built via Lillestrøm.[5] There were also ideas to run trains from the Hoved Line from Lillestrøm to Grefsen Station via the Alnabru–Grefsen Line, located adjacent to Storo, that would allow the central parts of Groruddalen to connect with the Ring Line and Nordre Aker.[6] When the operating company ordered new T2000 trains for the Holmenkoll Line, the design allowed future versions to have dual current systems, to handle both the 750 volts on the metro network (from a third rail and overhead wire), and the 15 kV 16.7 Hz AC system of the main railways. This would allow the Ring Line to share the physical track with the Gjøvik Line on the section from Storo to Sinsen.[7] The new T2ds were seen as a preparation for the Ring Line, and were optimised for higher speeds than the old stock, being capable of operating at 100 kilometres per hour (62 mph). At the same time, the Sognsvann Line was being upgraded to full metro standard, like the eastern part of the metro had, and would lose the overhead wires and get longer platforms.[8]

In 1992, the tram division of Oslo Sporveier launched an alternative Ring Line that would have been built as a light rail, using in part the existing tramway. In the west, it would follow the Sinsen Line via Sinsen to Storo. A new line would have to be built from Storo to Tåsen. The line would then use the existing Sognsvann Line to Majorstuen, where it would connect to the tramway and follow the Frogner Line into the city, via a new Vika Line through Aker Brygge. This alternative would cost NOK 61 million to build, compared to NOK 470 million estimated for the rapid transit solution. Named the Light Rail Ring (Norwegian: Bybaneringen), it would have 38 stops instead of 16 stops, and a travel time of 34 minutes instead of 22 minutes. Annual operating costs for the light rail solution would be NOK 57.5 million, compared to 43.9 million for the rapid transit solution.[9]

Between 1994 and 1998, there was local political debate about how Rikshospitalet, that was moving to Gaustad, should be served by public transport. The state wanted to extend the Ullevål Hageby Line of the tramway to the new hospital, while many local politicians wanted to use the rapid transit. Since the Ring Line would increase traffic on the Songsvann Line, moving the line was considered to better serve the hospital.[10] In 1998, an agreement was reached whereby the light rail line would be built, and a new station for transfer from the metro would open at Forskningsparken.[11]

A detailed proposal was presented by Oslo Sporveier in August 1996. It became clear that Berg would not be served by the Ring Line. Many neighbours to the route of the Sognsvann Line complained about this proposal, stating that they had hoped that the section from Majorstuen to Berg would have been rebuilt as a tunnel. They also argued that it was irrational that the line was running at-grade in densely populated areas, while it would run in a tunnel through the then mostly unpopulated Nydalen. To compensate, Oslo Sporveier stated that they would build noise screens along the line.[12] Also, the Norwegian Public Roads Administration protested to the plans, and stated that funding should be allocated to upgrading Ring 3 to six lanes before public transport investments were made in the area.[13]

The city council voted in favour of building the Ring Line on 25 June 1997, against the votes of the Progress Party. However, the decision did not include how the line would be financed, and the politicians stated that they were hoping that the state would use national road funds to finance the project.[14] This was partially ensured in December, when a political agreement was reached for Oslo Package 2, a financing plan for investments in public transport in Oslo and Akershus between 2002 and 2011.[15]

In December 1999, a disagreement arose between the Ministry of Transport and Communications and the city; the city would not except the government's promise to finance part of the line. Both Minister of Transport and Communications, Dag Jostein Fjærvoll from the Christian Democratic Party and Oslo City Commissioner of Transport and the Environment, Merete Agerbak-Jensen from the Conservative Party, agreed upon the distribution of funding from the city and state, and both wanted construction to start as soon as possible.[16] The city council did not accept the guarantees from the state until March 2000. Construction started in June, with the Agency for Road and Transport of the municipality responsible for construction. The city would pay NOK 224 million, while the state would pay NOK 673 million.[17]

The first section opened from Ullevål stadion via Nydalen to Storo on 20 August 2003,[18] costing NOK 590 million.[3] With the opening, line 4 was extended from Ullevål stadion to Storo.[19] Nydalen had grown up as an urban redevelopment area after the local industry had been abandoned in the 1980s,[18] where 14,800 jobs had been located by 2004.[18] On 20 August 2006, the final section opened, from Storo via Sinsen to Carl Berners plass,[20] with the whole project costing NOK 1,348 million.[3]

A report published by the city in 2007 declared the line a success and stated that all goals for the line had been exceeded. A survey conducted by the city in 2003 and 2007 showed that the Ring Line had a significant impact on the use of public transport in the area. Total public transport usage increased from 28 to 45%; use for commuting increased from 35 to 61%. At the Norwegian School of Management (BI), 85% of the students used public transport. The Ring Line reduced the estimated number of daily car trips by 10,000, and generated 11,000 more daily public transport trips. In 2007, daily passenger numbers at the stations were 8420 for Nydalen, 3630 for Storo and 2300 at Sinsen.[18] The line allowed travel time from the Nydalen and Storo to the city centre to be halved,[19] and travel time from Nydalen to the city center is faster by metro than by taxi.[13]

Route

The 5.0-kilometer (3.1 mi) Ring Line branches off from the Sognsvann Line after Ullevål stadion, just before Berg. It immediately enters a tunnel that runs via Nydalen to Storo. The station at Storo is just outside the entrance to the tunnel. From Storo to Sinsen, the tracks are laid parallel to the Gjøvik Line of the mainland railway. Also the Sinsen Line of the Oslo Tramway and the Ring 3 motorway follow the same corridor between the two stations.[3][20] The section between Ullevål stadion and Storo is 3.3 kilometres (2.1 mi), while the section from Storo to Carl Berners plass is 1.7 kilometres (1.1 mi). Of these, 4.0 kilometres (2.5 mi) are in tunnels.[19]

The Nydalen district, formerly an industrial area, has since undergone urban redevelopment. The immediate vicinity of the station includes several large workplaces. In 2005, BI, with 8000 students and faculty, moved into a new campus across the street from Nydalen Station.[13] Nydalen is the only underground station on the Ring Line. The escalators leading down to the platform features The Tunnel of Light, an artistic presentation of sound and colour around the passengers as they ascend from or to descend to the station. The artwork contains 1800 lights and 44 speakers. Nydalen also serves as a bus hub.[21]

Storo opened as a tram station as part of the Grünerløkka–Torshov Line on 28 November 1902.[22] It is located about 200 meters from Grefsen Station of the Gjøvik Line. The Norwegian National Rail Administration is planning to move the station platform so there can be direct transfer between NSB Gjøvikbanen's commuter rail services, and the metro.[23] Storo functions as a bus and tram hub; it serves line 11 and 12 on the Grünerløkka–Torshov- and Kjelsås Line, and line 13 on the Sinsen Line.[24]

Sinsen opened on 20 August 2006, three years after the two other stations.[1] The station is located close to, but not adjacent, to the tram stop Sinsenkrysset on the Sinsen Line (tram no. 17). Located at the interchange between Ring 3 and Trondheimsveien, it also serves as a bus hub.[24]

Lørensvingen, built in 2016, connected the Ring and Grorud Line. It splits from the Ring Line south of Sinsen, and run part in tunnel and part at-grade until it connects to the Grorud Line west of Økern. In the tunnel section the new station, Løren, was built. The day section runs parallel to part of the mainline Alnabru–Grefsen Line. The line allows metro trains to run directly from the Grorud Line to the Ring Line, and thus pass from east to west without passing through the packed Common Tunnel. It was part of the political compromise Oslo Package 3, completed by 2016.

Service

When operating a full circle route, trains start through the Common Tunnel. If running clockwise, they pass through all the common stations (Tøyen, Grønland, Jernbanetorget, Stortinget, Nationaltheatret and Majorstuen). They head north on the Sognsvann Line, stopping at Blindern, Forskningsparken and Ullevål stadion. The Ring Line proper then splits off, and the trains serve Nydalen, Storo and Sinsen, before Carl Berners plass on the Grorud Line. After that, the trains again enter the Common Tunnel at Tøyen.[25]

Line 5 operates the entire ring with a 15-minute headway. From east to west, trains on line 5 enter the common tunnel from the Grorud Line then make a full clockwise circle around the Ring Line, including a second pass of the common tunnel, before proceeding to the end of the Sognsvann Line.

Line 4, also with a 15-minute headway, serves all the stations on the ring except Carl Berners plass. As with Line 5, trains originate on the Grorud Line in the northeast, but they branch off at Økern and enter the Ring via the Løren Line. Line 4 trains then run counter-clockwise through most of the ring, branching off at Tøyen and continuing on the Lambertseter Line.

Travel time from Nydalen and Storo stations to the city centre stations is about the same, independent of which direction on the Ring Line travellers choose. Passengers heading for the city centre can therefore take the first train that comes, independent of which direction it is heading, thus giving Nydalen and Storo a five-minute headway service to the city centre. The trains are operated by Sporveien T-banen, a subsidiary of Sporveien, on contract with the public transport authority Ruter.[25]

Transfer to the Kolsås-, Røa- and Holmenkoll Line is available at Majorstuen; transfer to the Lamberseter, Østensjø- and Furuset Line is available at Tøyen and transfer to the Grorud Line is available at Carl Berners plass. Transfer to Oslo Central Station, which serves all trains in Eastern Norway, is available at Jernbanetorget. Most west-bound trains can also be reached at Nationaltheatret, and trains along the Gjøvik line can be reached at Grefsen Station, that is close, but not adjacent, to Storo.[26] The Oslo Tramway can be reached from several stations. In the city centre, transfer to all lines is possible at Jernbanetorget; all lines but no. 12 can also be reached at either Stortinget or Nationaltheatret. Lines 11, 12 and 19 all terminate at Majorstuen; lines 17 and 18 run via Forskningsparken; lines 11, 12 and 13 can be reached at Storo; and line 17 runs past Carl Berners plass.[24]

References

- Ruter (2008). "Tidslinje" (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 20 February 2009. Retrieved 21 March 2009.

- Berg, Reidar (14 April 1989). "Tbanering rundt hele sentrum!". Aftenposten Aften. p. 5.

- Oslo Package 2. "T-baneringen" (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on May 1, 2011. Retrieved 21 March 2009.

- Hegtun, Halvor (1 July 1989). "Ringbane rundt Oslo". Aftenposten Aften. p. 6.

- Vatne, Paul Einar (25 March 1991). "Ringbaneplan klar i april". Aftenposten Aften. p. 21.

- Pedersen, Håvard (10 December 1992). "Kollektivttilbudet Lokaltog på Alnabanen?". Aftenposten Aften. p. 7.

- Johansson, Erik W. (1995). "T2000 - AS Oslo Sporveiers nye T-banevogner". På Sporet. 81: 44–46.

- Amlien, Geir Arne (23 September 1991). "Tbanen skal satse på fart". Aftenposten Aften. p. 5.

- Mytting, Lars (3 June 1992). "Ring rundt Oslo til 61 mill". Aftenposten Aften. p. 16.

- "Neppe trikk". Aftenposten Aften (in Norwegian). 18 June 1996. p. 4.

- Lundgaard, Hilde (6 February 1998). "Oslo betaler trikk til Rikshospitalet". Aftenposten Aften (in Norwegian). p. 17.

- Voll, Kristin (5 August 1996). "Ring klar år 2000 Akerselva må flyttes". Aftenposten Aften (in Norwegian). p. 6.

- Rathe, Per (2009). "Med klokkertro på T-bane" (PDF). Transportforum (in Norwegian) (1): 12–15. Retrieved 29 March 2009.

- Lundgaard, Hilde (26 June 1997). "T-banering vedtatt". Aftenposten Aften (in Norwegian). p. 14.

- Haakaas, Einar (12 November 1997). "Oslo-pakke 2 godt mottatt, men ... Protester mot dyrere bomring". Aftenposten Aften (in Norwegian). p. 6.

- Ertzaas, Pål (12 November 1999). "Agerbak-Jensen og Fjærvoll enige om det meste - men T-banen i det blå Stillingskrig hindrer T- baneutbygging". Aftenposten Aften (in Norwegian). p. 10.

- Haakaas, Einar (14 March 2000). "Oslo kommune og staten er blitt enige T-baneringen på vei". Aftenposten Aften (in Norwegian). p. 12.

- Municipality of Oslo (3 January 2008). "T-baneringen en miljøsuksess" (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 2 October 2011. Retrieved 21 March 2009.

- Oslo Package 2 (2001). "Fellesløft for bedre kollektivtransport Oslopakke 2" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 October 2010. Retrieved 21 March 2009.

- Mo, Helene (21 August 2006). "Nå er ringen sluttet". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 2 November 2010. Retrieved 21 March 2009.

- Ruter (11 March 2008). "The Tunnel of Light" (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on June 15, 2008. Retrieved 21 March 2009.

- Aspenberg, Nils Carl (1994). Trikker og forstadsbaner i Oslo. Oslo: Baneforlaget. p. 10. ISBN 82-91448-03-5.

- Haga, Kristin Tufte (17 March 2008). "– Ikke nødvendig med undergang". Nordre Aker Budstikke (in Norwegian). Retrieved 21 March 2008.

- Ruter (2007). "Linjekart" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Archived from the original (pdf) on 26 March 2009. Retrieved 21 March 2009.

- Ruter (18 August 2008). "Rutetider T-banen" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Retrieved 21 March 2009.

- Ruter (18 August 2008). "Linjekart T-banen" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Retrieved 21 March 2009.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to T-baneringen. |