Riđani

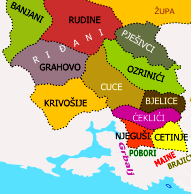

The Riđani (Serbian Cyrillic: Риђани) was a tribe in Old Herzegovina (later annexed by the Principality of Montenegro) that existed since the late medieval period, first mentioned in 1335, until the mid-18th century. The Krivošije, Grahovo and Rudine brotherhoods claim descent from the Riđani.

Pre-Ottoman history

The first mention of Riđani was in a 1335 document.[1] The territory where they lived was between the Zeta river in the Onogošt župa (county) and Ledenice near Risan[1] and Klobuk.[2]

In the first half of the 15th century, the Riđani tribe populated the territory between the mountains of Konavle, Dračevica and Vrsinje (modern day Zupci).[3] At that time, this territory belonged to the Duchy of Saint Sava. Their knez was Radivoj Sladojević.[4] According to some legends, they populated the territory of Krivošije and Cerovo Ždrijelo near Grahovo.[5]

The earliest Ragusan sources about this tribe are early 15th-century records in which they are mentioned as Vlachi Rigiani.[6] In 1429, the Ragusan senate invited them to take their livestock to Konavle mountains during the summer, for a certain fee.[7] Riđani had their own knez in 1435.[8] In a 1438 document, Đukan Milojević was mentioned as knez of Riđani.[9] Riđani frequently invaded the region of Konavle and robbed it, so Ragusans complained to Stjepan Vukčić Kosača.[10]

A 1441 document tells of their attacks and robbing of Ragusan merchant convoys.[7] One 1451 document indicate that Riđani populated the region between Risan, Kotor and Vrsinje.[11]

According to traditional belief, Riđani had been trying to migrate from their mountainous homeland to fertile lands of Grahovo (near Nikšić), facing resistance of its native people.[6] Eventually, Riđani became one of three strong tribes in the region of Onogošt, besides Drobnjaci and Lužani.[12] All three of them were governed by one ban.[12] Ugren was among the most notable bans.[12]

Ottoman era

After the Ottomans captured the region populated by Riđani it became known as the nahija of Riđani, with its seat in Grahovo.[13] An Ottoman governor administered the nahija, while the tribe was governed by its vojvoda (of Drobnjaci and Banjani) or by their knez (of Riđani).[14] In 1466 the subaşi of Riđani was Širmerd.[15] In 1469 Riđani were one of the "Vlach" tribes that participated in the kidnapping of a young male and female population of Konavle and Herzegovina. They sold them to Ottoman subaşi, vojvodas, martoloses and Muslims in Trebinje who sold them as slaves.[16] Riđani were registered in the first Ottoman defter (tax registry) of the Sanjak of Herzegovina, as part of the Novi kadiluk (modern-day Herceg Novi).[17] One of the knezes of Riđani in the Ottoman period was Sinan, who was also chieftain of Banjani, and son-in-law of Ali Paša Hercegović.[18]

In 1597, envoys of Serbian Patriarch Jovan Kantul and vojvoda Grdan, chieftain of Nikšići and Riđani tribes, reported to Pope Clement VIII about the possibilities to raise an anti-Ottoman rebellion.[19]

In 1649 the tribes of Nikšići, Riđani and Drobnjaci rebelled against the Ottomans and captured Risan, handing it over to the Republic of Venice.[20] In mid-17th century their chieftain was Radul of Riđani.[21] Riđani distinguished themselves in the struggle against the Ottomans, particularly during the late 17th-century Morean War.[22] Riđani slowly fled west to Herzegovina, especially after the Ottomans established Nikšić as their stronghold, while remnants of Riđani with newly immigrated Uskoks formed three tribal societies: Krivošije, Grahovo and Nikšićke Rudine.[22]

Montenegro and legacy

In 1749 the Montenegrin tribal assembly (zbor), which was the supreme governing body of Montenegro, decided to accept Riđani as their own.[23] After this event, the tribe ceased to exist, while its name is preserved in toponyms and folk tradition. Some modern-day Serbo-Croatian families (including the Merćep family) descends from the Riđani tribe.[24] During the 19th century, some families of the Kuči tribe believed that they descend from Riđani. The fact that Riđani and Kuči had the same slava (patron saint feast day) was used as an argument for such position. This belief is refuted by some authors who believed that this belief was result of the attempt to tie Riđani tribe to Kuči.[25] Riđani are mentioned in numerous songs of Serbian epic poetry.

Anthropology

In historical sources Riđani were referred to as "Vlachs"; Serbian scholars emphasize that they were referred to as Vlachs not because they were of Vlach (Romance-speaking) origin, but due to their occupation, as herdsmen ("Vlachs" being a derogatory term).[26] Some Serbian scholars refer to the Riđani as an "old Serbian tribe".[13] Maja Parović Pešikan hypothesized that Riđani were originally from Rhizon (originally an Illyrian settlement near Risan).[27]

The oldest brotherhood of Riđani were the noble Riđanići.[2] The larger brotherhoods of Riđani include the Krivošije.[2]

References

- Brozović 1999, p. 339.

- SNZ 1934, p. 7.

- Štamparija 1925, p. 40.

- Hrabak 1997, p. 146.

- Parovich-Peshikan 1980, p. 44.

- Knjiga 1980, p. 43.

- Vego 1957, p. 101.

- Samardžić 1892, p. 428.

- Štamparija 1934, p. 8.

- Vego 1982, p. 62.

- Knjiga 1980, p. 63.

- Delo 1971, p. 225.

- Katedra 1972, p. 146.

- Novak 1951, p. 306.

- Šabanović 1959, p. 158.

- Milić 1976, p. 14.

- Akademija 1992, p. 57.

- Naučna 1940, p. 545.

- Pejović 1981, p. 352.

- Ћоровић 1933, p. 345.

- Stanojević & Vasić 1975, p. 522.

- umetnosti 1978, p. 81.

- Banac 2015, p. 305.

- Mihić 1987, p. 309.

- Ekmečić 1995, p. 124.

- Ujević 1942, p. 119.

- Parović Pešikan 1972, p. 69.

Sources

- Knjiga (1980). Posebna izdanja. Naučna Knjiga.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Štamparija (1925). Spomenik Srpske kraljevske akademije. U Državnoj štampariji Kraljevne Srbije.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Banac, Ivo (9 June 2015). The National Question in Yugoslavia: Origins, History, Politics. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1-5017-0193-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Delo (1971). Glas. Naučno delo.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Katedra (1972). Prilozi prouc︣avanju jezika. Katedra za juz︣noslovenske jezike Filozofskog fakulteta.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ћоровић, Владимир (1933). Историја Југославије. Народно дело.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Novak, Viktor (1951). Istoriski časopis.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Samardžić, Radovan (1892). Istorija srpskog naroda: Doba borbi za očuvanje i obnovu države 1371-1537. Srpska knjiiževna zadruga.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Štamparija (1934). Letopis Matice srpske. U Srpskoj narodnoj zadružnoj štampariji.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Akademija (1992). Recueil d'études orientales. Akademija.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mihić, Ljubo (1987). Kozara: priroda, čovjek, istorija. Dnevnik.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vego, Marko (1982). Postanak srednjovjekovne bosanske države. Svjetlost.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pejović, Đoko (1981). Predmet i metod izučavanja patrijarhalnih zajednica u Jugoslaviji: radovi sa naučnog skupa, Titograd, 23. i 24. novembra 1978. godine. Crnogorska akademija nauka i umjetnosti.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Naučna (1940). Zbornik za istočnjačku istorisku i književnu gradju. Naučna knjiga.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ekmečić, Milorad (1995). Recuel de l'histoire de Bosnie et Herzegovine. SANU.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brozović, Dalibor (1999). Hrvatska enciklopedija. Leksikografski zavod "Miroslav Krleža". ISBN 978-953-6036-29-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hrabak, Bogumil (1997). Зборник за историју Босне и Херцеговине. Академија.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Milić, Danica (1976). Simpozijum Oslobodilački pokreti jugoslovenskih naroda od XVI veka do početka prvog svetskog rata. Istorijski institut.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- SNZ (1934). Letopis Matice srpske. U Srpskoj narodnoj zadružnoj štampariji.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ujević, Mate (1942). Hrvatska enciklopedija. Konzorcija Hrvatske enciklopedije.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Parovich-Peshikan, Maĭi︠a︡ (1980). Planinsko zaleće Rizinijuma: arheološke beleške iz Grahova, Krivošija i Cuca. SIZ kulture i naučnih djelatnosti--Nikšić.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Šabanović, Hazim (1959). Bosanski pašaluk: postanak i upravna podjela. Oslobodenje.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- umetnosti, Srpska akademija nauka i (1978). Posebna izdanja.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Parović Pešikan, Maja (1972). Starinar. Arheoloéski institut.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stanojević, Gligor; Vasić, Milan (1975). Istorija Crne Gore (3): od početka XVI do kraja XVIII vijeka. Titograd: Redakcija za istoriju Crne Gore. OCLC 799489791.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Јасмина Ђорћевић, ДРАЧЕВИЦА И РИЂАНИ СРЕДИНОМ XVI ВИЈЕКА, БЕОГРАД 1997

- Попис заорјенског племена Риђани с крајем-XV вијека (Зборник за оријенталне студије)

- М. ПЕШИКАН и М. ПАРОВИЋ-ПЕШИКАН, Од илирских Ризонита до заорјенских Риђана