Redstone Coke Oven Historic District

The Redstone Coke Oven Historic District is located at the intersection of State Highway 133 and Chair Mountain Stables Road outside Redstone, Colorado, United States. It consists of the remaining coke ovens built at the end of the 19th century by the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company. In 1990, it was recognized as a historic district and listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Redstone Coke Oven Historic District | |

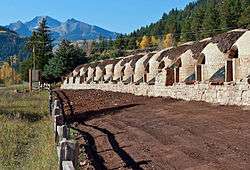

View south to Chair Mountain past remaining ovens, 2010 | |

Location within Colorado | |

| Location | Redstone, CO |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Aspen |

| Coordinates | 39°10′52″N 107°14′29″W |

| Area | 4 acres (1.6 ha) |

| Built | 1899 |

| Architect | Colorado Fuel and Iron |

| MPS | Historic Resources of Redstone |

| NRHP reference No. | 89002385 |

| Added to NRHP | February 7, 1990 |

Two hundred were built, because the coal in the surrounding mountains was ideal for refining into coke. At their peak, they were producing almost 6 million tons a year. The development was the beginning of the modern settlement of Redstone. There are very few coke ovens of their type remaining in the West;[1] the ovens are themselves the only remnant of the sizable coking operation in the area, the largest at the time in Colorado.

Within ten years of their construction the ovens fell into disuse when the mines closed. Their support steel was removed during the scrap metal drives of World War II, and later they were used as living space by hippies who moved into Redstone.[2] The possibility that some might be demolished to build a gas station eventually led Pitkin County to acquire the land in the mid-2000s,[3] and since then some have been restored.[4]

Geography

The remaining 90 coke ovens are arranged in a 600-foot–long (180 m) arc over a 4-acre (1.6 ha) area along the west side of Highway 133 south of Coal Creek just opposite where Redstone Boulevard crosses the Crystal River into downtown Redstone. There is a small parking area and interpretive plaque, the only contributing resource in the district other than the ovens.[5] In the middle is a gate leading to the current facility of Mid-Continent Coal & Coke, which now owns the property.[6]

Most of the structures are freestanding beehive ovens made of stone, their rounded tops covered with hardened brown earth. Some retain their original integrity; many have decayed visibly over the years. Four have been restored to their original appearance. A set in the middle, just north of the parking area and entrance, is within a stone retaining wall added in the mid-20th century (due to this, neither it nor the ovens it protects are considered to be contributing to the historic district[7]). Wooden guardrails and fences keep visitors from getting too close.

History

The history of the coke ovens is the history of Redstone. They went online during the town's peak period of population, and were shut down less than a decade later, never to be used again.[8] They were left to decay throughout much of the rest of the century, as Redstone itself nearly became a ghost town. A century after their construction, as the village turned around, they were restored as a historic attraction.[4]

1700s–1860: European settlement of the Crystal River Valley

The isolation of the Crystal Valley allowed the native Ute people to avoid contact with European colonists until they encountered the Spanish in the late 18th century. By the 1830s, traders and fur trappers were working in the region. The Astor family began supporting the latter during the next decade, and John C. Frémont led the first American expedition to the valley in 1843, returning two years later.[8]

Prospectors looking for gold in 1860 were disappointed, but named the 12,965-foot (3,952 m) Mount Sopris that dominates the valley after their leader. After the American Civil War, the federal government concluded treaties with the Utes and otherwise began to encourage settlement in the region, that its rich mineral resources might be exploited. The surveys of Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden in 1873 gave names to many other mountains and streams in the region and suggested the Crystal Valley might well be rich in coal.[8]

1880–1900: Early mine development

Silver and lead strikes led to the establishment of now-abandoned settlements like Crystal and Schofield further up the valley, along the river's upper forks in what is now Gunnison County. In 1880 the Ute ceded the area to European settlement, in preparation for their relocation to reservations elsewhere in Colorado and Utah the following year. Prospectors swarmed into the area, looking for all types of mineral deposits.[8]

In 1882, one of them, John Cleveland Osgood, was sent by the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad (CBQRR), which bought some of its coal from his employer, the White Breast Coal Company. His visit was part of a general survey of the state's coal resources, and he found them desirable enough that he set up the Colorado Fuel Company the following year to supply the Burlington and Missouri River Railroad, a CBQRR subsidiary, with coal. He had also found the Crystal River Valley's deposits ideal for coking, and bought land there.[8]

Four years later, he and his associates at Colorado Fuel set up both a toll road company and a railroad to make the valley accessible. Some surveying was done over the next two years, but no construction began. In 1888, the rival Colorado Coal and Iron Company built the Aspen and Western Railway to Willow Park, west of Carbondale, to exploit coal deposits there. The coal was found to be of poor quality, so plans for a coking facility there were canceled and the rail line abandoned the next year. Similarly, another rail line along the Crystal was surveyed and graded, but no actual tracks were ever laid.[8]

Afterwards, another Colorado Fuel subsidiary, Elk Mountain Fuel, was formed to buy land near the present site of Redstone in the area known as Coal Basin. It eventually merged with the parent, and in 1892, Colorado Fuel and its rival Colorado Coal and Iron merged to become Colorado Fuel and Iron (CF&I), controlling two-thirds of the state's coal mining and becoming the largest coal company in the West, headed by Osgood. The combined company was finally in a position to realize the transportation plans made over the past decade.[8]

Osgood planned to build a mining town, Coalbasin, high up the Coal Creek valley, where coal desirable for coking due to its purity and low ash content was abundant. From there, a narrow gauge railway would descend 12 miles (19 km) and 2,200 feet (670 m) to Redstone on the river, where coal could be both coked and transferred to standard gauge cars bound for Carbondale and other destinations via the Denver and Rio Grande Western and Colorado Midland. The Panic of 1893 delayed those plans, due to the failure of many of the state's banks and the ensuing difficulty in finding financing, to the end of the decade.[8]

1900–1925: Peak mining years and collapse

By the end of 1899, 249 ovens, the largest coking facility in the state, had been built by contractors from Denver.[4] They were operated by a work force that accounted for 10% of all Colorado's workers at the time. Coking workers were predominantly immigrants from Eastern Europe, whom the company had recruited from the East. Another mine was opened in Placita, to the south, and by 1902, the ovens had produced almost 5.7 million tons (5.2 million tonnes) of coke. Osgood developed the village of Redstone personally, at a cost of $5 million ($148 million in modern dollars[9])[10] as a planned community so that workers would have quality housing, frequently an issue in strikes of the era. Further up the valley, he built an estate he called Cleveholm but would later be known as Osgood Castle.[8]

The large work force was often restive, and their strikes hobbled CF&I at a time when it was making major investments in its Pueblo steel plant. Osgood turned to Eastern investors for help; by 1903, interests indirectly controlled by George Gould and John D. Rockefeller had gained control of CF&I. Osgood started the Victor American Fuel Company, which soon became CF&I's biggest competitor.[8]

CF&I's Pueblo plant became the state's largest coke buyer by the end of the decade. It was unprofitable to ship the fuel there from the Crystal River Valley, and by 1909 all mining and coking operations ended. Redstone was abandoned, with only a few residents remaining.[8] Osgood, who had largely retreated to New York City, returned to his estate in 1924 to attempt to redevelop the area as a resort. He died the following year, and his wife Lucille completed transforming the estate into a hotel. However, it failed due to the onset of the Great Depression shortly afterwards.[10]

1926–present: Neglect and restoration

At the outset of World War II, the community's population was down to 14.[10] During the war, the ovens' steel supports were removed during the scrap metal drives, leaving them vulnerable to structural decay. In 1953, some of the ovens near the center of the group were stabilized with a stone retaining wall,[7] when another company, Mid-Continent, began working the coal seams in the creek valley again.[3]

The other ovens suffered some decay, but were still structurally sound enough to avoid collapse. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, many of the young hippies and other countercultural youth of the time were drawn to the Colorado mountains, among other places, where they believed they could live lives closer to nature. Many came to Pitkin County to settle in its seat, Aspen, but some found the smaller and quieter Redstone more desirable instead. Some used the ovens as short- or long-term living quarters.[2]

Eventually the hippies left or settled in more traditional housing. Residents continued to pillage brick and stone from the ovens for occasional small jobs, even after they were listed on the Register. While none collapsed, a real threat emerged at the end of the 20th century, when Mid-Continent went bankrupt. As part of the division of its assets, it was proposed that a convenience store and gas station be built in the middle of the ovens, since the only one that had been on the 60-mile (100 km) stretch of Highway 133 between Carbondale and Paonia had closed.[4]

Residents, led by a member of the local historical society who called the ovens "the soul of Redstone", began working to save them. Initially, a state grant would have covered the cost, but it would have required an expansion of the historic district, which the landowner did not want, as they would not be able to further develop the site if the deal collapsed. As property values in the area increased in the early 21st century, the grant no longer would have covered the costs.[3]

The historical society needed someone to loan them the purchase price without any term or guarantee of repayment. In 2003, the Aspen Valley Land Trust was able to acquire the property under these conditions. A year later, it sold it at cost to the historical society, which then transferred the land to the county. It made up the difference between the $290,000 purchase price and the original state grant, and the 14 acres (5.7 ha)[4] including the ovens was finally protected.[3]

Later in the decade, the county began funding restoration efforts. The plan by the Aspen landscape architecture firm Bluegreen called for rebuilding part of the original wharf used to load and unload the ovens from adjacent railcars. In 2009, it won an Honor Award for Research and Communication from the Colorado chapter of the American Society of Landscape Architects.[11]

Work commenced in 2011, once the county had managed to procure the $800,000 required from a variety of state and federal sources. To stabilize the ovens, all vegetation around them will be removed and the masonry retaining wall partially rebuilt (although the ovens behind them will not be restored, as they were substantially altered when the wall was built). Four of the others will be restored to their original form, to the point that they could actually be used for coking again, save for the mortar being insufficiently heat-resistant. Another 56 will be stabilized without any reconstruction, and the remnant will be left as is to show the effects of time's passage.[4][7] Workers have found some relics of possible archeological interest inside the ovens, such as a pickaxe blade, though it is not known whether they came from the original mining era or the hippie years.[2]

References

- "Pitkin County". History Colorado. Retrieved July 27, 2011.

- Johnson, Kirk (September 24, 2011). "Giving New Life to Brick Ovens Where Hippies Once Roamed". The New York Times. Retrieved January 16, 2012.

- Frey, David (February 7, 2004). "Redstone coke ovens preserved" (PDF). Aspen Daily News. Aspen, CO. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 11, 2013. Retrieved January 16, 2012.

- Urquhart, Janet (May 30, 2011). "Redstone coke ovens return to former glory". Aspen Times. Aspen, CO. Retrieved January 16, 2012.

- Simmons, Laurie (October 1989). "National Register of Historic Places nomination, Redstone Coke Oven Historic District". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- Redstone Coke Oven Historic District (Map). ACME Mapper. Cartography by Google Maps. ACME Labs. Retrieved January 26, 2012.

- "Redstone Coke Ovens". City of Aspen/Pitkin County. 2002–2008. Retrieved January 20, 2012.

- Simmons, R. Laurie and Whitacre, Christine; "Historic Resources of Redstone Multiple Property Submission" (PDF)., History Colorado, March 1989, pp. 3–5. Retrieved January 16, 2012.

- Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- "The Redstone Story re-lives the industrialization of the West ..." Redstone Community Association. Retrieved January 20, 2012.

- "Redstone Coke Ovens". Bluegreen. Retrieved January 21, 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Redstone Coke Oven Historic District. |

- Pitkin County site on coke ovens, with updates on progress of restoration