Red Brick Roads

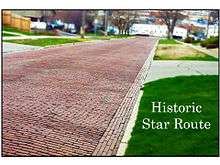

The Red Brick Roads, in Pullman, Washington, are a block of NE Maple St. and a block of NE Palouse St. and together are the last remaining brick streets in the city. The roads, paved in 1913, are important landmarks because they made transportation easier along the only of the city's Star routes, providing an essential connection between the Northern Pacific Railroad depot and the growing campus of Washington State College (now known as Washington State University). The steepest part of the route to campus (which included the block of what is today NE Maple St. and NE Palouse St.) received brick paving to provide traction for horses and automobiles—particularly during the difficult winter months.

Historic Star Route Pullman WA, 99163; NE Palouse St./NE Maple St. | |

|---|---|

| Nickname(s): Red Brick Roads |

.jpg)

Contextually Significant

Transportation context

Beginning in 1885, the railroad served as a vital communication and transportation link to the growing region. Pullman housed two railroad depots, the Northern Pacific Railway and the Oregon Railroad and Navigation Company (OR&N, most recently known as Union Pacific). The red brick street was built near the Northern Pacific Railway Depot as padding around the tracks for the pedestrians. Growing interest in the Palouse region led Northern Pacific Immigration officials to visit Pullman in the summer of 1913 and they were very impressed with the college campus and city, remarking that they were "sending immigrants to a paradise."[1] Due to the rapid growth and awareness of the region's significance, in 1917, Northern Pacific paid $40,000 for a "modern" facility, replacing the original depot. The pad was increased and laid in vitrified brick to match the adjacent "Palouse" or "Star Route" Street.[2] The railroad was the only means of travel that allowed people and students to leave and reenter the town during the late 1800s, and the Northern Pacific Railway and the OR&N ran special trains that allowed the students to leave school for breaks. Starting in the second decade of the twentieth century, automobiles began to dominate the landscape. Highways were built in the region, reducing the region's dependence on the railroad. In 1970, acquiescing to the automobiles dominance as a people-mover, Northern Pacific halted the use of passenger trains.[3]

"Historic Star Route"

Part of the Red Brick Roads was a Star route. Star routes were affiliated with the United States Postal Service and were distinguished as old mail routes that were also commonly known as Highway Contract Routes for delivering mail. From the Northern Pacific Railroad depot, the red brick paving continued up to Star Route St. (now known as Maple St.) to Montgomery St. (today known as Campus St.) then east to the center of the college. Star Route was a very dusty and muddy horse and buggy road during the early 1900s. During the winter it was very difficult to travel and in 1906 a wooden sidewalk was constructed to aid foot traffic. On February 9, 1907 the Pullman Herald wrote concerning the safety of Star Route: "[It is] the most dangerous road in the county… there is an almost perpendicular drop off of 18-20 feet with the Northern Pacific Track lying beneath. If a team should run away on coming down Star Route it would in all probability dash over the yawning precipice and death would be inevitable".[4] The city and residents of Pullman saw paving as a solution to the dangers and inefficiencies of the unpaved dirt road.

Funding the roads

Automobiles accompanied horse carriages in Pullman by 1912. The high traffic streets were used by both automobiles and horses, which required the streets to be surfaced. The Pullman Chamber of Commerce played an early role in establishing the importance of paved streets by forming the Pullman Good Roads Committee in 1911. The Pullman Good Roads Committee immediately began formation of a plan to pave a route to be determined from the preexisting streets from the city to the college. The properties adjacent to the roads paved would be responsible to pay taxes and in addition, the college and community businesses would help fund the project as well. The Good Roads Committee advocated for new roads and helped the college receive the Mill Tax (an early form of property tax), which increased revenue to the college to allow them to expand and improve the campus. The roads benefited the local economy by allowing deliverymen to reduce prices for customers because they could operate year round.[5] The route was chosen through College Hill because it was the lowest slope of the several city to campus routes.[6] The preferred paving surface was Macadam and concrete curbing; brick was used on high sloped sections of the streets to help horses get traction to climb up the hills. Due to the increasing enrollment to the college and population growth of the city, the roads had a significant amount of automobile and carriage traffic by the time they were paved. The lack of speed limits on automobiles soon became an issue after the paving was placed and on May 23, 1913, Pullman addressed the speed issue and passed an ordinance to limit the speed to 12 mph for automobiles and horses.[7]

College campus context

The presence and growth of Washington State College (today known as Washington State University), inspired Pullman citizens to clamor for the paving of the city's historic star route. The first streets that were paved on College Hill began at the Northern Pacific Railroad depot across from Palouse street. The high traffic areas of Pullman required paving for horses, mail routes, and for some of the first automobiles. In 1912, to meet the growing needs on the transportation infrastructure, Pullman implemented street improvements.[8] The street was and remains a significant avenue for the campus, for it increased the efficiency and access to transportation by carriage and eventually by automobile, allowing generations of students to attend class.

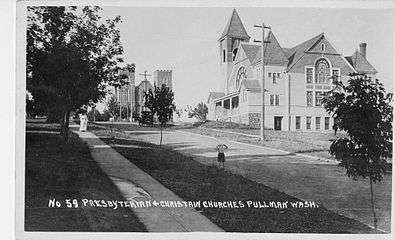

Spiritual surroundings

The Red Brick Roads have a connection to Pullman's spiritual community, for Pullman's first Presbyterian church chose to locate along them. In the late 1890s, President Enoch A. Bryan of Washington State College called for a church where students could worship. He purchased land on Star Route and led the drive to build Pullman's first Presbyterian church—completed in 1899 at a cost of $4,000. The money came partly from Dr. W. A. Spalding of the First United Presbyterian Church of Spokane, Washington, plus monies that Bryan raised in the community. Within fifteen years the rapid growth of the college and the Pullman community necessitated the construction of a larger church. In 1914, the old church was lifted, rotated, and incorporated into a new structure clad in Tenino stone. The new church was praised by the Pullman Herald as a "permanent and lasting piece of art which speaks well of the city." [9] Following a renovation and reconfiguration in the mid-2000s, the former church is now a multi-unit dwelling knowns as the Greystone Apartments, with some of the original wooden trusswork and stained glass still visible. The structure, which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, is a substantial presence at the northern edge of the Red Brick Roads.

The original Pullman Hospital

In 1912, the first hospital was built along the brick roads—specifically along what was officially called Star Route. Originally named "Campbell's Hospital" with the address of 1507 Star Route, it is currently located on the corner of Campus St. and Maple St. However, in 1912 Dr. Campbell renovated it and renamed it "The Pullman Hospital." The hospital originally operated as a private facility, but after renovation it was converted to a public hospital. Historically, the Red Brick Roads played a vital role in assisting the transportation of patients to the hospital.

References

- "Northern Pacific Immigration Officials Pleased With Pullman". Pullman Herald. August 22, 1913.

- "$40,000 Northern Pacific Depot Comes To Pullman". Pullman Herald. May 5, 1916.

- "Brief Local News". Pullman Herald. December 23, 1921. Retrieved March 3, 2013.

- "Editorial". Pullman Herald. Feb 9, 1907. Retrieved March 3, 2013.

- "Dr. Egge's Theories on Paving". Pullman Herald. December 19, 1913. Retrieved March 3, 2013.

- "Road To College Will Be Paved". Pullman Herald. February 3, 1911. Retrieved March 3, 2013.

- "Pullman, Wa". Ordinance No. 240. 1913.

- James, Lindsay (1923). An Economic History of Whitman County, Washington. Pullman, WA: Washington State University.

- Evans, Michael. "Greystone Church and Foundation Records". Washington State University Libraries Manuscripts, Archives, and Special Collections. Missing or empty

|url=(help)