Rebecca Parrish

Sarah Rebecca Parish (November 1, 1869 – August 22, 1952) known as Rebecca Parrish, was an American medical missionary and physician in the Philippines.[3]

Rebecca Parrish | |

|---|---|

| Born | Sarah Rebecca Parish November 1, 1869 |

| Died | August 22, 1952 (aged 82) |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | M.D. |

| Alma mater | Medical College of Indiana |

| Occupation | Medical missionary |

| Years active | 1906-1933 |

| Employer | Women's Foreign Missionary Society of the Methodist Episcopal Church |

| Known for | First female doctor to practice in the Philippines |

Notable work | Establishment of the Mary Johnston Hospital in Manila |

| Parent(s) | Jesse Mallow Parrish Mary Catherine Mitchell |

Born in Crawfordsville, Indiana, Parrish attended the Medical College of Indiana. After working as an assistant physician, she joined the Women's Foreign Missionary Society of the Methodist Episcopal Church which sent her to work in Manila, Philippines. She spent 30 years in the Philippines, becoming the first female doctor to practice in the country and greatly improving health in the area. She is widely credited for being the driving force behind the Mary Johnston Hospital, which provided maternal care and services to impoverished people and for establishing the first nurses training institute in the country.[4]

Early life: 1869-1906

Parrish was born to Jesse Mallow Parrish and Mary Catherine Mitchell in 1869, raised as the eldest of nine children. She was raised in a small frontier cabin on a farm in Logansport, Indiana. A very religious family, The Parrishes would attend the Bethel Methodist Episcopal Church. As a child she was described as "earnest, thoughtful, always solicitous and serious". She decided she wanted to be a missionary doctor at a young age after hearing stories from a missionary magazine called The Heathen Women's Friend. Her plans were interrupted when her parents died, and she moved her family to Indianapolis to care for her siblings while attending school at Clinton County Normal School.

After graduating she started teaching at grammar schools in order to support her eight siblings. After attending Chicago Training School for one year, she decided to enroll in medical school at the Medical College of Indiana. Despite suffering frequent illnesses due to stress and overwork she graduated fourth in her class of 47 students in 1901. After interning at Wesley Hospital for a year she applied to be a missionary physician but she was denied because of her ill health, so instead, she worked as an assistant physician at North Indiana Hospital for the Insane from 1902 to 1906. In 1906 when she was in the hospital recovering from another illness, she received a letter from the Woman's Foreign Missionary Society of the Methodist Episcopal Church informing her that she was appointed to work in Manila, Philippines, to which she immediately agreed.[5]

Missionary career: 1906-1933

Arrival in Manila

When Parrish arrived in Manila she encountered a country reeling from the Philippine Revolution that ended three centuries of Roman Catholic rule under Spain. She arrived immediately following the Philippine-American War, during which the United States fought from 1899-1902 to suppress the nationalist forces of Emilio Aguinaldo who sought independence rather than American occupation. During this time United States forces burned villages, tortured suspected guerrillas, and employed civilian reconstruction policies that were seen as imperialist. The conflict resulted in widespread violence, famine and disease, as well as prevalent hatred for the American government.[6] The country was suffering from a lack of sanitation, clean drinking water, and proper nutrition.[4] Because of the tropical climate of the Philippines, leprosy was widespread. She later described the health situation:

"Health is always a problem in the tropics; water is not safe, unless artesian wells are drilled. In the old days, with decaying fruits and vegetables, insects, especially mosquitoes, insufficient fresh milk for the babies, and the prevalence of cholera, smallpox, malaria, leprosy, dysentery, and tropical ulcers and eruptions, there was a serious health question."[7]

Health care in the Philippines was still in the early stages of development,[8] although was starting to improve thanks to the efforts by Taft Commission to promote development and prepare the Philippines for eventual independence. (Country Studies 29, 37) The area subsequently became a hub for religious and medical missions.[9] However, many people were distrustful of hospitals because of local religious beliefs and practices.[5] The Methodist Episcopal Church had sent several medical missionaries and teachers, but Parrish was the first female missionary physician, and became the first female doctor to practice in the Philippines.[10]

Dispensaria Betania: 1906-1908

Within two months she started seeing patients in a small free dispensary in December 1906.[11] When it first opened, the dispensary had only "a few drugs, an enameled bowl, a pitcher with most of the enamel peeled off, and chair with one leg awry." The dispensary was located inside of the Harris Memorial Training School (now known as Memorial College) in Santa Cruz, a neighborhood in the northern part of Manila.[8] The church had commissioned the school three years earlier to train young Filipina girls in Manila as deaconesses. She called her clinic the Dispensaria Betania or Bethany Dispensary and quickly acquired a small stock of drugs and medical tools. She operated under the rule that no patient was ever turned away. The clinic received so many patients that it was soon converted into a small hospital with the acquisition of ten cots. The Training School opened up a Nurses' Training School to accommodate her needs. Three students from the Harris Memorial Training School became her first student nurses, and the following year she was assisted by several American nurses as well. She made many house calls during her time at the clinic as an opportunity to follow up with her patients, as well as to tell them about Christianity. She started to develop sympathy for her patients, writing, "It is nonsense to say 'East is East and West is West and never the twain shall meet', for 'In Christ there is no East or West, in Him no North or South.'".[10] Death rates among children dropped as she provided medicine, treatment and milk to hundreds of mothers.[5] Her work increased as more and more people traveled by foot, by horse and even by boat to visit the clinic. Her work was made easier in 1911 when the first class of 6 Filipina women graduated from nurse's training. She became devoted to her role as both a physician and a missionary, even writing an article asking for donations in the Michigan Christian Advocate. In it she described her trip to a village across Manila Bay during which she witnessed a communion service in which there was no place to kneel because the dirt floors had turned to mud from a rainstorm.[10]

Mary Johnston Hospital: 1908-present

| Mary Johnston Hospital | |

|---|---|

Hospital Facade | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Morga Street, Tondo, Manila, Philippines |

| Coordinates | 14.609023°N 120.966288°E |

| Organization | |

| Type | Non-stock, non-profit mission hospital |

| History | |

| Opened | 1908 |

| Links | |

| Website | http://www.maryjohnston.ph/ |

| Lists | Hospitals in the Philippines |

Establishment of the hospital

In 1908[4] it became clear that the Dispensaria Betania was not sufficient to meet the needs of the community. The local Filipinos in Manila raised between $5,000 and $10,000 to expand the clinic, but the efforts were greatly aided by the assistance of Daniel B.R. Johnston, an American real estate broker. Johnston was seeking to build a memorial to his recently deceased wife Mary, who had been active in promoting missionary work. The Women's Foreign Missionary Society, hearing this, sought him out told him about Parrish's work in Manila, asked him to build a hospital there as a memorial. He donated $12,500 to build the hospital, with the request that it be named after his wife. Parrish decided to build the hospital in Tondo, an impoverished district in western Manila. In 1908 the Mary Johnston Hospital for Women in Children, a two-story building with a fifty-five patient capacity was opened.[10] The hospital included departments for medicine, surgery, obstetrics, pre-natal care, pediatrics, orthopedics and public health.[5]

Hospital practices

Parrish left the clinic to work at the new hospital, which specialized in maternity and child care and stood as the only Protestant hospital in the region. It still operated under the original principle that no patient ever be turned away, often meaning that Parrish worked 20-hour days. She maintained high medical standards for the hospital and required all workers to be involved in the hospital's evangelistic program. She held daily Bible lessons at the clinic and nightly prayer services at the hospital. Despite donations, the hospital still struggled financially. It got by on local and overseas donations, many brought in by Parrish who was frequently invited to speak about her work at gatherings and events. Some donors like the Masonic Lodge donated outright gifts, like an entire ward to house crippled children. Her work became more than a hospital, but rather a fixture in the community, so much so that new generation of children came to be known as "Dr. Parrish's children". She was known to inspire former patients to return and volunteers to devote their lives to medical missionary work.

On February 25, 1911, only three years after it was erected, the hospital burned down and was closed for four months.[10] It was able to reopen, thanks to gifts and donations.[8] The hospital always struggled financially and often benefitted from philanthropic assistance, once receiving a donation when it was down to its last 65 cents. The famed opera singer Madame Schumann-Heink once visited and was so impressed that she gave a special performance to benefit the hospital.[5] By 1941 her hospital had grown big enough to hold 120 patients, 60 nurses and in addition to student nurses, and continued to uphold the policy of never turning away a patient.[8]

World War II

After Japan declared war on the United States in 1942, they invaded the Philippines soon after, as a U.S.-controlled territory.[12] The Mary Johnston Hospital was quickly transformed from a women's and children's hospital into an emergency hospital where patients who were injured during air raids could be treated. Many other hospitals in the city were destroyed or taken over, so Mary Johnston experienced an influx of patients while simultaneously seeing a reduction in many of its sources of income. Many of the personnel worked without pay in order to keep it running.

The hospital was destroyed again in a fire on February 5, 1945, when the Japanese finally retreated from the Philippines. Five years later the hospital reopened, thanks to generous gifts from American donors, one individual donation was approximately $28,000.[8] It was rebuilt yet again, this time more extensive and spacious. As years went by the hospital added a maternity ward, a clinic and a station to provide milk to malnourished infants and toddlers.[10]

Later years: 1950-1958

The Filipino government expressed its gratitude for the services provided by the hospital on several occasions. A bill was passed by the Philippines Legislature giving the hospital financial assistance and extending the hospital's lease to allow it to continue operating.[4]

In 1950, at the age of 80 Parrish was honored with a gold medal from the Civic Assembly of Women in Manila, awarded by the President Elpidio Quirino of the Republic of the Philippines, although she was unable to be in Manila at the time due to her failing health. The medal read: The blessings of health and social welfare which the Philippines enjoy today have been inspired by the pioneering effort of this sincere and determined American missionary doctor, who came a long way across the sea, bringing Christian love, healing, and enlightenment, and a better way of life.[10]

The hospital reopened the following year on August 26, 1950, and was inaugurated by the President, who said in his speech "I wish there were more hospitals in the country that could render as much service as this hospital has rendered." This time the hospital remained a general hospital.[8] At the time of Parrish's death the hospital was planning to open a new maternity wing in 1958 to celebrate the upcoming 50-year anniversary of the opening of the Dispensaria Betania. Upon hearing the news of her death, all activities were halted in order to hold a Thanksgiving service in her honor. When the time of the anniversary came, the maternity ward was dedicated as the "Rebecca Parrish Pavilion" with a plaque reading

- Rebecca Parrish Pavilion

- In Appreciation of Her Years

- of Sacrificial Service for

- Mothers and Babies of

- The Philippines[10]

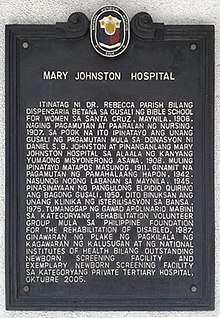

Modern day

The Mary Johnston Hospital is credited with drastically reducing infant mortality by providing advice on proper nutrition, care and sanitation. Today the hospital still stands as one of the primary hospitals in Manila and is distinguished for its commitment to Christian care and to serving primarily impoverished patients.[10] It stands as the only Methodist Hospital in the Philippines. On December 8, 2006, the National Historical Institute of the Philippines recognized it as a historical site.[4]

The poor people of Tondo goes to the Dispensary to receive free medical care.

The structure, which was once a small clinic, is now a general hospital which serves as a training center for doctors, nurses and other medical professionals. It offers free medical care for Tondo, one of Manila's poorest districts.[13]

As part of the hospital's community outreach, it adopts neighborhood communities to focus on livelihood education, health, cleanliness and Christian education. It also provides a milk-feeding program and conducts semimonthly clinics to administer immunization shots.[13]

Personal life

Beliefs

Parrish was always regarded as the leading figure guiding the Mary Johnston Hospital, combining its medical duties with her religious mission. A Born Missionary Recounts "…she saw to it that the hospital and its environs maintained a high moral standard in a district not noted for propriety. No money raised through bridge-teas, dancing, or theatricals was accepted as a contribution to the hospital. She lectured on ethics, morals and religion in local high schools and universities; taught sociology for ten years; wrote a health page and health articles for newspapers. Often she found herself being interviews by young people for advice, even marital counseling." She was also noted for her activism, campaigning against the practice of white slavery and the mistreatment of lepers.[5] She devoted herself to women's issues in Manila as well, she recounts encountering sexism upon her initial arrival "They asked me point blank, "Can a woman know enough to be a doctor?" and I, as frankly, answered "yes". All were curious. But, thro 27 years, I was to prove it…and DID a million times."[9] This determination led her to establish the Philippines' first Woman's Club, which later expanded to 800 clubs and was incorporated into the General Federation of Women's Clubs.[5]

Return to the United States

In 1933, after 27 years in the Philippines Parrish's health gave out and she was forced to return to the United States. But by the time she left, her hospital had expanded to include 500 Filipino nurses and had reduced the infant mortality rate from 66% to 8%. She continued to lecture about her mission work, as well as write articles and letters.[10] She detailed her experiences in a memoir titled Orient Seas and Lands Afar.[3] Although Parrish longed to visit the hospital once more, her anemia prevented her from traveling and in 1952 she died in her sleep before she was able to return.[10] She died on August 23, 1952, at the age of 82 in Indianapolis, Indiana.[3][7]

References

- "California, San Francisco Passenger Lists, 1893-1953 Image California, San Francisco Passenger Lists, 1893-1953; pal:/MM9.3.1/TH-1942-22242-17271-77 — FamilySearch.org". Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- Windsor (2002, p. 160)

- "Dr. Rebecca Parrish, Medical Missionary". The New York Times. 24 August 1952.

- "Mary Johnston Hospital". General Commission on Archives and History. Archived from the original on 8 January 2014. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- Devolder, Mary (1956). Rebecca Parrish: A Medical Missionary in Manila. Women's Division of Christian Service, Board of Missions, The Methodist Church Literature Headquarters.

- "MILESTONES: 1899–1913". United States Department of State. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- Windsor, Laura Lynn (2002). Women in medicine : an encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. p. 160. ISBN 978-1576073926.

- "History". Mary Johnston Hospital. Archived from the original on 7 October 2013. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- Parrish, Rebecca (1945). Through clinic doors. History of Mary Johnston hospital. Indianapolis: Tri-Art Press.

- Walls, Anne C. Kwantes ; foreword by Andrew F. (2005). She has done a beautiful thing for me : portraits of Christian women in Asia. Manila, Philippines: OMF Literature. pp. 163–172. ISBN 9789715118941.

- Ogilvie, Marilyn; Harvey, Joy (2000). The biographical dictionary of women in science. New York [u.a.]: Routledge. p. 981. ISBN 978-0415920384.

- "U.S. forces land at Leyte Island in the Philippines". A&E Television Networks, LLC. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- Gilbert, Kathy (October 18, 2007). "Struggling hospital continues to offer free health care". UMC.org. United Methodist Church. Retrieved 21 October 2014.