Ravedeath, 1972

Ravedeath, 1972 is the sixth studio album by Canadian electronic music musician Tim Hecker, released on February 14, 2011 by Kranky. The album was recorded primarily in Frikirkjan Church, Reykjavík, by Ben Frost. It makes prominent use of pipe organ, and was described by Hecker as "a hybrid of a studio and a live record."[3] It received universal acclaim from critics, with many reviewers acknowledging the album as Hecker's finest.

| Ravedeath, 1972 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | February 14, 2011[1] | |||

| Recorded | July 21, 2010 | |||

| Studio | Frikirkjan Church, Reykjavík, Iceland[2] | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 52:24 | |||

| Label | Kranky | |||

| Tim Hecker chronology | ||||

| ||||

Writing, recording and release

The album was written by Hecker during late 2010 in Montreal and Banff, Canada.[2] The majority of the album was recorded in Fríkirkjan Church, Reykjavík, Iceland; the location was discovered as a possible recording venue by Frost.[3] Hecker recorded the bulk of the album on July 21, 2010,[2] playing compositions on the pipe organ which were further complemented by guitar and piano.[4] Following this concentrated recording session, he returned to his studio in Montreal and worked for a month, undertaking the mixing and completing the record.[3] The result, as Hecker described it, is "a hybrid of a studio and a live record."[3]

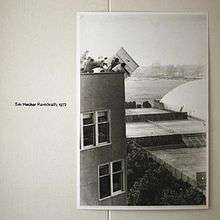

The cover depicts MIT students pushing a piano off the roof of the undergraduate dorm Baker House in 1972 – an act which began a long-running university ritual.[5] Inspired by "digital garbage – like when the Kazakhstan government cracks down on piracy and there's pictures of 10 million DVDs and CDRs being pushed by bulldozers", Hecker found the artwork and developed the cover concept himself, licensing the artwork from the MIT archives and re-photographing the image.[5]

The '1972' of the album's title is a reference to the cover artwork – the inaugural piano drop occurred in 1972 – but word 'Ravedeath' has unclear connotations, even to Hecker himself. At a rave in 2010, the word occurred to Hecker, and became "the wrongest and the most right title ever. It had a life of its own after a while."[3]

The album was released in CD and double LP format by Kranky on February 14, 2011.[6] Hecker subsequently released a companion EP, named Dropped Pianos, later in 2011. It serves as a "starker and colder" counterpoint, utilising "heavy reverb and minor-key tones, [producing] lots of negative space".[7] The EP's cover art is yet another re-photographing of the MIT image used for Ravedeath. While the image has been re-photographed in a different setting, it is unclear whether it was a negative of the image that was re-photographed, or simply a variation that has been inverted.[7]

Sound and structure

While an oft-used label, the name "ambient" was deemed a "lazy term" by No Ripcord, but serves as a "tool of recognition" for the album.[8] Beats Per Minute describes the music as "drone-based tempests with a mixture of laptop, keyboard, tape and effects-drenched guitar".[9] The album makes extensive use of pipe organ, which "sets the album's tone from the outset",[9] alongside "[l]ingering piano chords [which] slip over the droning throb of the buried pipe organ";[10] although "many may not identify an organ as the source of the music at all".[10]

A diverse range of recording artists have been used as reference points to describe the sound and tone of the album. "Studio Suicide" is likened to shoegaze artists My Bloody Valentine and Slowdive,[8] while other parts of the album have called reviewers to invoke Pink Floyd, Bach, Silver Apples and Vangelis.[9] Minimalist composer Terry Riley and guitarist John Martyn are likewise alluded to,[4] while a PopMatters review underlined the power of the album when saying that it can be "more bone-chilling than Cannibal Corpse at their most bloodthirsty."[11]

The album's unique recording context – its location and technique – was deemed a vital component of its sound,[9][12] one described as "evocative, moving and expressive".[12] Tonally, melody "tends to remain subordinate to texture",[9] meaning "Hecker's music is not easy or accessible. There are hints of melody but these are always subservient to mood, texture and feeling. There is little or no percussion and rhythm is not a prominent element."[12] This results in "a dark and often claustrophobic record",[13] as No Ripcord's Marc Higgins concludes that "the record is awash with the feeling of isolation".[8]

Reviewers found that the record did not conform to a typical structure. As a PopMatters reviewer analyzed, "The record seems to have no center, no shining single moment, no climax or vortex. Instead it hovers lightly but ominously, like the notes in the songs themselves, hanging in midair without ever dropping to the floor. Each time a track threatens to spill over and crash, it doesn’t."[11] There was, however, a divide to be found; the second half's tracks "are subtler than those in the first half and give the album a sense of balance and a natural arc".[13] In Hecker's own words, "In the beginning, it's a false start, a kind of a turn-away, like 'Don't cross. This river it's filled with blood,' or something... [But] that tension and anxiety slowly dissipates towards the end of the record and it has an almost romantic finish to it."[3]

Theme

Tim Hecker, interviewed by Vincent Pollard[3]

Reviewers roundly acknowledged the album's thematic centre, as the album "seems to be pointing at an end to music, or the endlessness of music".[8] A MusicOMH review expands on this: "[o]ne of Hecker's major concerns is decline and degradation. The album's title and a number of the individual track titles suggest that this preoccupation is still very much in his mind. Yet the titles also suggest some sort of internal, personal conflict – perhaps even a crisis of confidence."[12] Joe Colly's Pitchfork review delves deeper into this idea: "it seems that the organ sounds Hecker captured back in that Rejkjavik church represent a certain purity of sound and that the digital noise battering it throughout act as the enemy, the corrosive effect. There's an ongoing struggle between the two that's mirrored in the menacing song titles and gripping cover art. It's important, then, that the album closes with "In the Air III", a track that features almost no interference whatsoever, just the plinking organ by itself. If I'm reading it right, it feels like Hecker's point is that music, in its purest form, survives no matter what you throw at it".[13]

Reception

| Aggregate scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AnyDecentMusic? | 8.0/10[14] |

| Metacritic | 86/100[15] |

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| The A.V. Club | A−[17] |

| Drowned in Sound | 9/10[4] |

| Fact | 4.5/5[18] |

| Mojo | |

| MusicOMH | |

| NME | 7/10[20] |

| Pitchfork | 8.6/10[13] |

| Resident Advisor | 4.0/5[21] |

| Uncut | |

Ravedeath, 1972 received widespread acclaim from music critics upon release. At Metacritic, which assigns a normalized rating out of 100 to reviews from mainstream critics, the album has an average score of 86 out of 100, which indicates "universal acclaim" based on 17 reviews.[15] The album has been described as Hecker's "most claustrophobic", in the same breath as being "his most powerful",[9] and his "most successful" album.[12] Reviewers for Pitchfork and Rock Sound acclaimed it as Hecker's "finest work to date".[13][23] Set in the context of the ambient genre, Beats Per Minute's Ian Barker holds that it "quietly stand[s] a shade taller than many of its peers".[10]

Both Pitchfork and Uncut placed the album at number 30 on their respective lists of the top 50 albums of 2011,[24][25] while The Quietus named the album #3 on its rundown the top albums of 2011.[26] The album was longlisted for the Canada-based 2011 Polaris Music Prize,[27] and in March 2011 it won the Juno Award for best Canadian Electronic music album.[28] In 2019, Pitchfork ranked the album at number 136 on their list of "The 200 Best Albums of the 2010s".[29]

Track listing

All tracks are written by Tim Hecker.

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "The Piano Drop" | 2:54 |

| 2. | "In the Fog I" | 4:52 |

| 3. | "In the Fog II" | 6:01 |

| 4. | "In the Fog III" | 5:01 |

| 5. | "No Drums" | 3:24 |

| 6. | "Hatred of Music I" | 6:11 |

| 7. | "Hatred of Music II" | 4:22 |

| 8. | "Analog Paralysis, 1978" | 3:52 |

| 9. | "Studio Suicide, 1980" | 3:25 |

| 10. | "In the Air I" | 4:12 |

| 11. | "In the Air II" | 4:08 |

| 12. | "In the Air III" | 4:02 |

| Total length: | 52:24 | |

Personnel

Writing and performing[2]

- Tim Hecker – writing and recording

Technical[2]

- Paul Corley – engineering

- Ben Frost – engineering and additional piano

- David Nakamoto – artwork layout

- James Plotkin – mastering

Release history

| Date | Label | Catalogue number | Format |

|---|---|---|---|

| 14 February 2011 | Kranky[6] | krank154 | 2×LP |

| CD |

References

- Dombal, Ryan (November 18, 2010). "Tim Hecker Announces New Album". Pitchfork. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- Ravedeath, 1972 (Digipak liner notes). Tim Hecker. Kranky. 2011. krank154.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Pollard, Vincent (February 16, 2011). "Tim Hecker Talks Ravedeath, 1972". Exclaim!. Retrieved August 4, 2011.

- Bliss, Abi (March 14, 2011). "Album Review: Tim Hecker – Ravedeath, 1972". Drowned in Sound. Retrieved August 4, 2011.

- Dombal, Ryan (January 28, 2011). "Take Cover: Tim Hecker: Ravedeath, 1972". Pitchfork. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- "Tim Hecker: Ravedeath, 1972". Kranky. Retrieved August 4, 2011.

- Masters, Marc (October 10, 2011). "Tim Hecker: Dropped Pianos". Pitchfork. Retrieved May 12, 2013.

- Higgins, Marc (April 7, 2011). "Tim Hecker: Ravedeath, 1972". No Ripcord. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- Power, Chris (February 8, 2011). "Review of Tim Hecker – Ravedeath, 1972". BBC Music. BBC. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- Barker, Ian (February 18, 2011). "Album Review: Tim Hecker – Ravedeath, 1972". Beats Per Minute. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- Newmark, Mike (May 18, 2011). "Tim Hecker: Ravedeath, 1972". PopMatters. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- Paton, Daniel (February 14, 2011). "Tim Hecker – Ravedeath, 1972". MusicOMH. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- Colly, Joe (February 18, 2011). "Tim Hecker: Ravedeath, 1972". Pitchfork. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- "Ravedeath 1972 by Tim Hecker reviews". AnyDecentMusic?. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- "Reviews for Ravedeath, 1972 by Tim Hecker". Metacritic. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- Raggett, Ned. "Ravedeath, 1972 – Tim Hecker". AllMusic. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- Williams, Christian (March 22, 2011). "Tim Hecker: Ravedeath, 1972". The A.V. Club. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- Mugwump, Jonny (February 15, 2011). "Tim Hecker: Ravedeath, 1972". Fact. Archived from the original on April 4, 2016. Retrieved May 3, 2019.

- "Tim Hecker: Ravedeath, 1972". Mojo (209): 100. April 2011.

- "Tim Hecker: Ravedeath, 1972". NME. 2011.

- Rauscher, William (February 11, 2011). "Tim Hecker – Ravedeath, 1972". Resident Advisor. Retrieved February 11, 2011.

- "Tim Hecker: Ravedeath, 1972". Uncut (167): 83. April 2011.

- Marshall, Joe (February 14, 2011). "It's hard to imagine that 2011 will see many finer releases". Rock Sound. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- "Staff Lists: The Top 50 Albums of 2011". Pitchfork. December 15, 2012. Retrieved January 8, 2012.

- Breihan, Tom (November 29, 2011). "Uncut's Top 50 Albums Of 2011". Stereogum. Retrieved May 12, 2013.

- "Here Be Monsters: Quietus Albums Of The Year 2011". The Quietus. December 16, 2011. Retrieved December 15, 2011.

- "2011 Polaris Music Prize Long List announced". aux.tv. Archived from the original on October 2, 2015. Retrieved June 16, 2011.

- "Artist Summary | The JUNO Awards". Juno Awards. CARAS. Retrieved April 28, 2013.

- "The 200 Best Albums of the 2010s". Pitchfork. 8 October 2019. Retrieved 9 October 2019.