Ralph A. Ofstie

Ralph Andrew Ofstie (16 November 1897 – 18 November 1956) was a Vice Admiral in the United States Navy, an escort carrier commander in World War II, Deputy Chief of Naval Operations (Air), and Commander of the U.S. Sixth Fleet. He was born in Eau Claire, Wisconsin[2] and his hometown was Everett, Washington.[3]

Ralph Andrew Ofstie | |

|---|---|

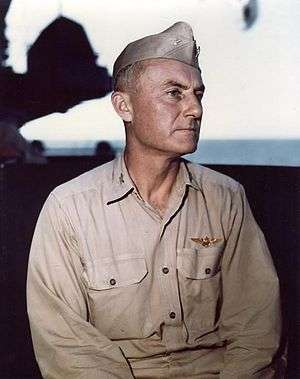

Captain Ralph A. Ofstie on the bridge of USS Essex 1944 | |

| Born | 16 November 1897 Eau Claire, Wisconsin |

| Died | 18 November 1956 (aged 59) Bethesda Naval Hospital, Maryland |

| Place of burial | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1918–1956 |

| Rank | Vice Admiral |

| Commands held |

|

| Battles/wars |

|

| Awards |

|

Naval Academy and World War I

Ofstie was born in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, in 1897 to a Norwegian father and Swedish mother who had emigrated from Stjørdal, Norway in 1896.[4] He enrolled in the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis, Maryland in 1915, graduated tenth of his class and was commissioned an Ensign in June 1918. During World War I, he served on the destroyer Whipple (DD-15) and the cruiser Chattanooga (CL-18) where he saw duty in the Eastern Atlantic and in European Waters. He was promoted to Lieutenant (junior grade) in August 1918. After the war, he was transferred to the destroyer O'Bannon (DD-177).[3]

Early career

In 1920 Ofstie reported to Naval Air Station Pensacola, Florida for Navy Pre-Flight School. Upon completion, he attended Naval Flight Training school which he completed in 1921 and was designated a Naval Flight Officer. His first air squadron was Fighter Squadron VF-1 "Wolfpack" where he served from 1922 to 1924. With other Navy pilots in the 1920s, Ofstie participated in annual flight competitions with Army pilots in the Curtiss Marine aircraft.[3]

In 1924-1925 he was assigned as Commanding Officer of Scouting Squadron VS-6. From 1927 to 1929 he served as Aviation Officer of the light cruiser Detroit (CL-8). From 1929 to 1933 Ofstie served in the Flight Test Division at Naval Air Station Anacostia.[3]

Returning to sea aboard the carrier Saratoga (CV-3) in 1933, Ofstie took command of Fighter Squadron VF-6 for the next two years. Promoted to Lieutenant Commander he was assigned as Assistant Naval Attaché in Tokyo, Japan, and upon completion of that duty he returned to sea as Navigator on the carrier Enterprise (CV-6). As an interim assignment, he served on staff duty aboard the carrier USS Saratoga in 1939 before returning to the Enterprise.[3]

Before the United States entered World War II, Ofstie served on staff duty on the carrier Yorktown (CV-5) in 1940. With the war in Europe already underway, he next served as Assistant Naval Attaché in London, England.[3]

World War II

Ofstie's first wartime assignment in the United States was as a Commander on the staff of Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander United States Pacific Fleet, at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii.[3]

Promoted to Captain, from 6 November 1943 to 7 August 1944 he commanded the large carrier Essex (CV-9). During his tenure on Essex, Ofstie was involved in several naval actions. Essex took part in her first amphibious assault at the Battle of Tarawa. Her second amphibious assault delivered in company with Task Group 58.2 was against the Marshall Islands in January to February 1944. As part Task Group 68.2 Essex participated in the attack against Truk, Operation Hailstone, in February 1944. Essex struck Marcus and Wake Islands in May 1944 and finally deployed with Task Force 58 to support the Battle of the Philippine Sea and the occupation of the Mariana Islands in June 1944.[3]

Escort Carrier Commander and Battle off Samar

In August 1944 Ofstie was promoted to Rear Admiral and was assigned as Commander Task Group 32.7/Carrier Division 26 with his flag in the escort carrier USS Kitkun Bay (CVE-71) for the invasion of Palau in September.[3]

Keeping his flag in Kitkun Bay, Carrier Division 26 moved to the Philippines to support the Battle of Leyte Gulf. Ofstie was assigned to Rear Admiral Clifton Sprague's Task Unit 77.4.3 code name "Taffy III" where his unit was heavily involved in the Battle off Samar. Pitted against a Japanese naval force consisting of 4 battleships, 6 heavy cruisers, 2 light cruisers, and 11 destroyers, led by Vice Admiral Takeo Kurita, Ofstie's COMCARDIV 26 escort carrier USS Gambier Bay (CVE-73) was sunk by Japanese naval gunfire. For this service at Samar, Ofstie was awarded the Navy Cross.[3]

Rear Admiral Ofstie's last sea command in World War II was as COMCARDIV 26 at the Invasion of Lingayen Gulf, Philippines, in January 1945. Next, he was assigned to the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey of Japan where he played a key role in interviewing many of the surviving Japanese officials.[3]

Post war service

In 1946, Ofstie was assigned to the Joint Chiefs of Staff Evaluation Group and served at the nuclear tests at Bikini Atoll.[3]

On 11 October 1949, Rear Admiral Ofstie testified before a committee and stated, "strategic air warfare, as practiced in the past and as proposed for the future, is militarily unsound and of limited effect, is morally wrong, and is decidedly harmful to the stability of a post-war world." These comments were related to the "Revolt of the Admirals".[3]

During the Korean War from 1950 to 1951 Ofstie was Commander of Task Force 77. After the Korean War he served as Deputy Chief of Naval Operations (Air).[3]

Last duties and death

Ofstie's last tour of duty was as Commander, Sixth Fleet in European waters from 1955 to 1956. After only a year, however, Ofstie fell ill and returned to Bethesda Naval Hospital where he died on November 18, 1956.[2][3]

Vice Admiral Ralph Andrew Ofstie and his wife, Captain Joy Bright Hancock (Ofstie), are buried together in Section 30, Grave 2138, at Arlington National Cemetery.[3]

References

- Notes

- "Military Times Hall of Valor : Awards for Ralph Andrew Ofstie". militarytimes.com. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

- "Vice Admiral Ralph A. Ofstie". The Bee. November 19, 1956. p. 26. Retrieved June 20, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Biography of RADM Ralph A. Ofstie, USN". bosamar.com. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

- 1956 Admiral Ralph Ofstie - Historiefortelleren (PDF) (Norwegian) historiefortelleren.no Retrieved 7 March 2019

- The Battle Off Samar - Taffy III at Leyte Gulf by Robert Jon Cox

- Bibliography

- Cox, Robert Jon (2010). The Battle Off Samar: Taffy III at Leyte Gulf (5th Edition). Agogeebic Press, LLC. ISBN 0-9822390-4-1.

- Morison, Samuel E. (1958). History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Leyte, June 1944 - January 1945, Volume XII. Edison, New Jersey: Castle Books. ISBN 0-7858-1313-6.

- Y'Blood, William T. (1987). The Little Giants: U.S. Escort Carriers Against Japan. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-275-3.