Rajputs of Nepal

Rajputs of Nepal (Nepali: नेपालका राजपुत) or anciently Rajputras (Nepali: राजपुत्र) are Rajput community of Nepal. As per the 2011 Nepal census, the population of Rajputs is reported at 41,972.

45th Chauhan Sirdar Hardayal Singh of the Tulsipur State which was centred in Awadh region of Uttar Pradesh, India but also had territories in Nepal | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 41,972 (2011 Nepal census)[1][2] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Nepali, Maithili, Bhojpuri | |

| Religion | |

| Hinduism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Chathariya Shresthas, Thakuris, Maithils and other Indo-Aryan peoples |

There were various historical groups of Rajputs from ancient and medieval India that have immigrated to Kathmandu valley, Khas Malla Kingdom, Western hill regions and other Terai territories. The Nepalese dynasty of Indian plain origin were Lichhavis[3] who were Rajputs[4] and entitled themselves with the archaic title Rajputra.[5] The heavy Rajput immigration into Nepal began on the rise of Muslim conquests in the Indian subcontinent after the 12th century CE.[6][7][8] These Rajputs particularly settled in Kathmandu valley, as well as in the various hills of the Himalayan ranges specially the Western-Central Nepal.[9] Those Rajput groups in the Western Nepal led into disintegration of Khas Malla Kingdom and formation of large number of confederated states called Baise Rajya and Chaubisi Rajya.[9] The Rajputs of the Kathmandu Valley established marital relations with the Newar Malla rulers of the Kathmandu valley, who were of Rajput origin themselves. Notable of these Malla Rajputs was the famed ruler Jayasthiti Malla[10] who established Hindu reforms and social regulations among the Newar people of Kathmandu Valley. Rajput families from Indo-Gangetic plain were routinely invited by the Mallas of the Kathmandu valley and a new noble class of courtiers, presently called "Thakoo/Thakur" and part of the Chatharīya Srēstha caste, were developed from the descendants of the plain Rajputs in the Malla court.[11] The Shah court also heavily favored Rajputs as legal regulations in the Kingdom of Nepal were inclined to them making them one of the Hindu high caste in the Tagadhari group[12] and a faction not permitted to be enslaved in Nepal.[13]

Some writers are of the opinion that the Rajputs of Nepal, are of spurious descent and many families claimed Rajput descent for political purposes.[14]

Legends and Chronicles

According to some legendary accounts in the chronicles such as the Gopal Genealogy and Wright Genealogy, the Gopālavaṃśi/Gopal Bansa or "Cowherd Family" are said to have ruled Nepal especially the Kathmandu valley for some 491 years. They are said to have been followed by the Mahiṣapālavaṃśa or "Buffalo-Herder Dynasty", established by a Rajput from Indo-Gangetic plain named Bhul Singh.[15]

History

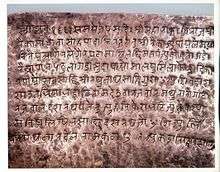

Lichchavi Rajputras

Lichhavis were the first Nepalese dynasty of Indian plain origin who began their rule in the 4th or 5th century.[3] Historian Baburam Acharya in an interview asserts that Amshuverma and the Lichhavi rulers were all Rajputs and Kshatriyas.[4] Lichchavi inscription self describes them as Rajputras (princes).[4] Rajputras who were ranked Kshatriyas, had special role in politics during the Lichchavi period. The Lichchavi inscription of Sikubahi (Shankhamul) mentions about Rajputra Vajraratha, Rajputra Babharuvarma, and Rajputra Deshavarma.[5] Rajputra Babharuvarma and Rajputra Deshavarma were Dutakas (diplomats) in the reign of King Gangadeva and Amshuvarma respectively. [5] Similarly, the Lichchavi inscription of Sanga mentions the name of Rajputra Vikramasena who was a Dandanayaka (judge).[5] The Lichchavi inscription of Deopatan mentions Rajputra Shurasena as well as the inscriptions of Adeshwar mention the names of Rajputra Nandavarma, Rajputra Jishnuvarma and Rajputra Bhimavarma.[5] Thus, historian Dhanavajra Vajracharya concludes that Rajputra of Kshatriya ranks were found abundantly in the topmost position in the Lichchavi court.[5]

Khas Rajputs

The Baleshwar Inscription of King Krachalla (or Krachalla Deva) of Khas Malla Kingdom at capital Dullu[16] self proclaimed that he belonged to a Buddhist Jina family of hill Rajput background.[17] The inscription mentions his two regional chiefs (Mandalikas) as Rawat Rajas.[17]

Few groups of Hindus including Rajputs were entering Nepal before the fall of Chittor due to regular invasions of Muslims in India.[9] After the Fall of Chittorgarh in 1303 by the Alauddin Khilji of the Khalji dynasty, Rajputs from the region immigrated in large groups into Nepal due to heavy religious persecution. The incident is supported by both the Rajasthani and Nepalese traditions.[6][7][18][9][note 1] Indian scholar Rahul Ram asserts that the Rajput immigration into Nepal is an undoubted fact but there can be questions in purity of blood of some leading families.[21] Historian James Todd mentions that there was a one Rajasthani tradition that mentions the immigration of Rajputs from Mewar to Himalayas in the late 12th century after the battle between Chittor and Muhammad Ghori.[8] Historian John T Hitchcock and John Whelpton contends that the regular invasions by Muslims led to heavy influx of Rajputs with Brahmins from the 12th century.[22][23]

The Hindu immigrants including Rajputs were mixed into the Khas society quickly as a result of much resemblance.[9] The entry of Rajputs in the central Nepal were easily assisted by Khas Malla rulers who had developed a large feudatory state covering more than half of the greater Nepal.[9] Also, the Magar tribesmen of Western Nepal welcomed the immigrant Rajput chiefs with much cordiality.[24] After the late 13th century, the Khas Empire collapsed and was divided into Baise Rajya (22 principalities) in Karnali-Bheri region and Chaubise rajya (24 principalities) in Gandaki region. These Baise and Chaubise kingdoms were ruled by Rajputs and several decentralized tribal polities.[9] Historian and Jesuit Ludwig Stiller contends that the Rajput intervention to the political affairs of Khas Malla Kingdom was significant reason behind the disintegration of the kingdom and he further conjectures:

Though they were relatively few in number, they were of higher caste, warriors and of a temperament that quickly gained them the ascendancy in the princedoms in the Jumla Kingdom, their effect on the kingdom was centrifugal.

— Ludwig Stiller's "The Rise of House of Gorkha"[9]

Newar Rajputs / Newar Mallas, Thakurs and Chathariyas

In 1380 A.D., the last Baish Thakuri King, Arjun Dev or Arjun Malla, was ousted by his ministers and was displaced by a Rajput King Sthiti Malla.[10] Sthiti Malla self proclaimed as a Kshatriya of Sun-god descent. [25] Sthiti Malla's successor, King Jyotir Malla and his successors invited Rajput families from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, and began marital relations with them.[11] The sons of Jyotirmalla were given the Rajput surname Singh while other sons were given the surname Malla.[11] Rajput bridegrooms were procured from Bihar regions and were married to their daughters of the Malla rulers.[26] These Rajput son-in-laws were included in the gotra of the Malla rulers[26] and the son-in-law who lived with their Malla father-in-laws were given the surname Singh.[11] Thus, the Rajput families became courtiers at Nepal and created a new endogamous courtier (Bharadari=Bharo) class.[11]

Rajput influx also occurred in the 14th century with the arrival of Karnat king Hari Simha Dev (14th century CE) and the entourage that came along with him to Kathmandu Valley with the attack of the Tirhut kingdom by Ghiyath al-Din Tughluq of Tughluq dynasty in 1324 CE. These Rajputs similarly established marriage alliances with the existing Malla kings.[27] These Mallas and its courtier clans have now coalesced into a single caste group of Newar Kshatriya caste, locally called Chatharīya, which is believed to be the derivative of the word ‘Kshatriya’, the second varna of the traditional Hindu varnashrama comprising kings, warriors and administrators. The Chatharīyas consider themselves as the Raghuvamshi Kṣatriya descendants of the Karnat king Hari Simha Dev (14th century CE) and the Rajput entourage that came along with him.[28] The Rajput clans that arrived at this time, and that have been transformed as present surnames among the Chatharīyas, include Raghuvanshi, Rawal, Raithor, Chauhan, Chandel, and Hada. The presence of these notable present Chatharīya clan titles clearly non-indigenous to the Newars that are still prevalent among the present-day Rajputs of India has been suggested as evidence of the Chatharīya's claim to their ancestry.[29] Additionally, these Rajput descendants who are seen as the highest segments of the present-day Chatharīya caste; clans like Malla, Pradhan, Pradhananga, Patrabansh, Bharo, Raghubanshi, Rajbansh, Rajbhandari, Onta, Amatya, Chauhan, Raithor, etc. are given the highest "Thakur/Thakoo" status, while other Chatharīyas are lesser elevated, albeit still retaining their Chatharī/Kșatriya status. These Thakurs and Chatharīyas, are nonetheless, accorded the second highest caste-status among Newars after the Rajopadhyaya Brahmins.[30]

In Jang Bahadur Rana's caste ordering in the Muluki Ain, Chatharīyas were placed among the Tagadhari dwij-jati status of upper twice-born castes.[31] The Muluki Ain refers them as tharghar ra asal sresth pointing out to the clans/houses as being of noble descent and being a real Shrestha, the archaic honorific term.[32]

Gorkhali Rajputs

After the Rajput immigration in Western Nepal, Shah dynasty and their Thakuri clans began claiming descent from Rajput refugees of Chittor whose fort was sieged twice by the Muslim invaders in 1303 and 1568.[23] The Raja Vamshavali (royal genealogy) written by Chitravilasa on the instigation of King Rama Shah of Gorkha Kingdom as well as the Goraksha Vamshavali (Goraksha genealogy) links the royal dynasty of Gorkha to the ruling Rawal Rajput family of Chittor.[33] Richard Temple asserts that the some of the ruling dynasties of Nepal valley were of patrilineal "Aryan Rajput" descent and matrilineal aboriginal descent.[34] He further contends that the royal house of Gorkha were such half-caste Rajputs.[34]

Ramakrishna Kunwar, a Gorkhali Kunwar noble claimed descent from Rana Rajput family of Mewar

Ramakrishna Kunwar, a Gorkhali Kunwar noble claimed descent from Rana Rajput family of Mewar

Kanwar, a historical Chhetri clan, self pro-claimed descent from Rana Rajputs of Chittor and received the title of Rana.[35] The older version of their genealogy states that Kunwars were descended from a Rajput prince, Ram Singh Rana, a grand-nephew of the ruler of Mewar.[36] The newer version of their origin published by Prabhakar, Gautam and Pashupati Shamsher Jang Bahadur Rana states that they were descended from Kunwar Kumbhakaran Singh, younger brother of Guhila King of Mewar, Rawal Ratnasimha. During the first siege of Chittorgarh in 1303 A.D., Kumbhakaran Singh's descendants left Mewar to north towards Himalayan foothills.[37]

Rajput, Chhetri and Thakuri

Historian Baburam Acharya referred Chhetri as Rajputs in the Pyuthan state of Chaubise rajya where the group was placed opposed to Khawas (slave) or Matwali (liquor drinkers).[38] These Rajputs spoke the Nepali language of the Aryan language family.[38] During the reign of Mukunda Sen, Rajput Chhetris particularly Thapa, Rawal, Kunwar, Khatri and Khadka came from western regions and settled in his kingdom.[39] Similarly, the Muluki Ain entitled "On Adultery and Slavery Among the Madhesiyas of the Tarai" mentions the Rajput Chhetri caste.[40] Historian John T Hitchcock mentions that in Western Nepal and Kumaon, the Rajputs were either plain origin or Khas origin.[41] He further referred Chhetris as "Khas Rajputs".[42]

Thakuris who are regarded as ruling clans of Nepal are also referred to as Rajputs.[43] Prayag Raj Sharma mentions that the Rajputs referred in the Muluki Ain (Legal Code) were Thakuris.[44]

Rajput architecture

During the period of Malla Kings, the architecture was of Mughal style.[45] However, the architecture during the period of King Prithvi Narayan Shah was a Rajput style of architecture.[45] King Prithvi Narayan Shah built the 115 feet high palace named Kailash to the south of Kathmandu palace in the Rajput style of architecture. He kept his eldest son and Crown Prince Pratap Singh Shah in the palace.[46] During the rule of King Rana Bahadur Shah, a large house was built in Deopatan based on the Rajput style. A sanatorium was built for the treatment of Queen Kantiwati based on the Rajput style.[45] As Mukhtiyar Bhimsen Thapa rose, the European architecture increased in popularity ending the period of Rajput architecture.[47]

Provisions relating to Rajputs

The royal order by King Girvan Yuddha Bikram Shah dated Kartik Badi 10, 1860 V.S. (November 1803) declares that neither Brahmin and Rajput could be enslaved throughout the Kingdom of Nepal.[13][note 2] The royal order by King Girvan Yuddha Bikram Shah promises to remit homestead taxes and levies to all Rajputs residing in the Kingdom of Nepal and exempts compulsory labor obligations to the royal court with restoration of their confiscated properties except those confiscated in the conquest.[48][note 3] King Rajendra of Nepal issued royal orders with effect of enforcement from Ashadh Sudi 7, 1893 (July 1836) prohibiting sexual relations with widowed sister-in-law (i.e. wife of elder brother) among all castes and such act was made punishable by provisions as per the caste of the perpetrator.[49][note 4] The punishment for the non-royal Rajput male perpetrator on that offence was ‘’cutting of genitals’’.[49] The legal code enacted on the reign of King Surendra of Nepal shows that the Brahmins of Jaisi caste were punishable by five of NRs. 40 if the male Jaisi Brahmin committed sexual offence to a Rajput girl without establishing commensal relationship with the girl and were punishable by NRs. 60 on the same assault with establishing commensal relationship with the girl.[50]

The royal order dated Kartik Badi 6, 1920 V.S. (November 1863) by King of Nepal Surendra Bikram Shah allows Thakuris and Rajputs of Kingdom of Nepal with fiscal privileges of exemption on payment of Serma 1 levies in lieu of compulsory labor (Jhara, Khara, Beth, Begari, Hulak), Walak until 1919 V.S. as well as exemption on levies payable to Zamindars and local administrators (Amali) from the year 1920 V.S.[51] [note 5] The additions made in Muluki Ain (Legal Code) until 1922-23 Vikram Samvat (1865-66) consists two titles of provisions specially on Rajputs: [52]

114. Rajput ko Hadnata (Incest among Rajputs).

147. Ghati badi jat ma karani garnya Rajputko (Law relating to Rajputs who commit illicit sexual intercourse with women of higher or lower caste).

As per the Muluki Ain titled ‘’On Adultery and Slavery Among the Madhesiyas of the Tarai’’, the a man of the Matwali caste of Terai is punishable with imprisonment up to 3 years if he commits adultery with the female of Rajput Chhetri without commensality. If he was proven with commensality, the punishment increases to 6 years on the case.[40]

Modern (21st century)

The caste with the largest ratio of representation in the civil service in Nepal is, the Rajput, who have a presence in the civil service that is 5.6 times that of their presence in the population.[53]

Notable people

- Amshuverma, a Rajput ruler of Lichchavi Kingdom

- Jayasthiti Malla, a Rajput (Malla son-in-law) ruler of Malla Kingdom

- House of Tulsipur, Rajput rulers of Chauhan Dynasty Prithvi Raj Chauhan

See also

References

Footnotes

- Scottish scholar Francis Buchanan-Hamilton doubts the first tradition of Rajput influx to Nepal which states that Rajputs from Chittor came to Ridi Bazaar in 1495 A.D. and went on to capture the Gorkha Kingdom after staying in Bhirkot.[19] He mentions the second tradition which states that Rajputs reached Palpa through Rajpur at Gandak river.[6] The third tradition mentions that Rajputs reached Palpa through Kumaon and Jumla.[20]

- From King Girban,

Kartik Badi 10, 1860 (November 1803)

It had been the practice in the region between the Bheri River and the Mahakali river to enslave Brahmans and Rajputs. From today, no Brahman or Rajput shall be enslaved throughout our territory. Other ryots too shall be enslaved only with their consent, in the presence of the respectable persons of village, not through the use of force.

Kartik Badi 10, 1860 (November 1803)[13] - From King (Girban) to Rajputs all over the kingdom.

We hereby remit all homestead taxes and levies, as well as compulsory labor obligations, due on the Raikar lands occupied by you and your slaves, servants, tenants, etc. to the palace, and remain constantly prepared to obey our commands. We also restore to you your remaining property, slaves, etc. other than property confiscated during the conquests, or slaves freed by the Bhardars.

Monday, Magh Sudi 5, 1857 (January 1801)[48] - This provision exempted the Kirantis, Limbus, Lapches and Jumlis from punishment for the time being.[49]

- From King Surendra Bikram Shah,

To all the Rajputs and Thakurs residing in our country.

Prime Minister Jung Bahadur, acknowledging the help rendered in 1911 in the war with Tibet and in 1914 in the battle of Lucknow, has uplifted the status if Khas and made them equal to Chhetris. He has permitted Magars and the Gurungs to be promoted up to the rank of Colonel, and now they are enlisted in the regular army. Other classes of subjects (Prajas) too have been enlisted as soldiers, and companies have been formed of them. He has promulgated a law which prohibits the enslavement of Newars who were traditionally enslaved. Limbus and Kiratis have also been recruited in the army and a company has been formed of them. Their enslavement has been prohibited. Thakuris, Rajputs and other castes have been exempted from payments which they had been making until 1919 of Serma 1 levies in lieu of compulsory labor (Jhara, Khara, Beth, Begari, Hulak), Walak and levies payable to Zamindars and local administrators (Amali) from the year 1920 up to 4 annas, 8 annas, 12 annas and 1 rupee respectively. You are directed to present yourself whenever required by us and to carry out the tasks assigned to you.

Dated Kartik Badi 6, 1920 (November)[51]

Notes

- http://cbs.gov.np/image/data/Population/Population%20Monograph%20of%20Nepal%202014/Population%20Monograph%20V02.pdf

- "Nepal Census 2011" (PDF).

- Pradhan 2012, p. 2.

- Regmi 1973a, p. 146.

- Vajracharya 1975, p. 239.

- Hamilton 1819, pp. 129-132.

- D.R. Regmi 1961, p. 14.

- Todd 1950, p. 209.

- Pradhan 2012, p. 3.

- Acharya 1970, p. 4.

- Acharya 1970, p. 12.

- "How discriminatory was the first Muluki Ain against Dalits?". 2015-08-21.

- Regmi 1969a, p. 44.

- Nagendra Kr Singh (1997). Nepal: Refugee to Ruler : a Militant Race of Nepal. APH Publishing. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-81-7024-847-7.

- Shaha, Rishikesh. Ancient and Medieval Nepal (1992), p. 7. Manohar Publications, New Delhi. ISBN 81-85425-69-8.

- Atkinson 1971, p. 273.

- Atkinson 1971, p. 272.

- Wright 1877, pp. 167-168.

- Hamilton 1819, pp. 240-244.

- Hamilton 1819, pp. 12-13,15-16.

- Ram 1996, p. 77.

- Hitchcock 1978, pp. 112-113.

- Whelpton 2005, p. 10.

- Pandey 1997, p. 507.

- Acharya 1970, p. 11.

- Acharya 1975b, p. 186.

- Gellner and Quigley (1995). Contested Hierarchies A Collaborative Ethnography of Caste among the Newars of the Kathmandu Valley, Nepal. Clarendon Press: Oxford Studies in Social and Cultural Anthropology. ISBN 978-0-19-827960-0.

- Rosser, Colin (1966). Social Mobility in the Newar Caste System. In Furer-Haimendorf.

- Bista, Dor Bahadur (1967). People of Nepal. Kathmandu: Ratna Pustak Bhandar.

- Gellner and Quigley (1995). Contested Hierarchies A Collaborative Ethnography of Caste among the Newars of the Kathmandu Valley, Nepal. Clarendon Press: Oxford Studies in Social and Cultural Anthropology. ISBN 978-0-19-827960-0.

- Bista, Dor Bahadur (1967). People of Nepal. Kathmandu: Ratna Pustak Bhandar.

- https://www.nepjol.info/index.php/OPSA/article/download/1133/1558 Harka Gurung; The Dalit context

- Acharya 1976a, p. 172.

- Temple 1970, p. 138.

- Regmi 1975a, p. 91.

- Wright 1877, p. 285.

- Rana, Prabhakar S. J. B.; Rana, Pashupati Shumshere Jung Bahadur; Rana, Gautam S. J. B. (2003). "THE RANAS OF NEPAL".

- Acharya 1976b, p. 225.

- Acharya 1976b, p. 226.

- Regmi 1969b, p. 49.

- Hitchcock 1978, pp. 118-119.

- Hitchcock 1978, p. 116.

- Gurung 1994, p. 21.

- Sharma 2004, p. 133.

- Acharya 1975a, p. 165.

- Acharya 1973, p. 57.

- Acharya 1975a, p. 166.

- Regmi 1975b, p. 222.

- Regmi 1971, p. 2.

- Regmi 1970b, p. 285.

- Regmi 1970a, p. 19.

- Regmi 1976a, pp. 88-90.

- Dhakal, Amit (11 June 2014). "निजामती सेवामा सबैभन्दा बढी प्रतिनिधित्व राजपूत, कायस्थ र तराई ब्राम्हण". Setopati. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

Books

- Pradhan, Kumar L. (2012), Thapa Politics in Nepal: With Special Reference to Bhim Sen Thapa, 1806–1839, New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company, ISBN 9788180698132

- Regmi, Mahesh Chandra (December 1, 1969a), "Documents On Slavery" (PDF), Regmi Research Series, 1 (2): 44–45

- Regmi, Mahesh Chandra (December 1, 1969b), "On The Madhesiyas Of The Tarai" (PDF), Regmi Research Series, 1 (2): 49–50

- Acharya, Baburam (January 1, 1970), "Nepal, Newar And The Newari Language" (PDF), Regmi Research Series, 2 (1): 1–15

- Regmi, Mahesh Chandra (January 1, 1970a), "Fiscal Privileges of Rajputs And Thakurs,1863" (PDF), Regmi Research Series, 2 (1): 19

- Temple, Sir Richard (June 1, 1970) [1887], "Remarks On A Tour Through Nepal In May, 1876" (PDF), Regmi Research Series, 2 (6): 136–144

- Regmi, Mahesh Chandra (December 1, 1970b), "The Jaisi Caste" (PDF), Regmi Research Series, 2 (12): 277–285

- Regmi, Mahesh Chandra (January 1, 1971), "Sexual Relations With Widowed Sisters-In-Law" (PDF), Regmi Research Series, 3 (1): 1–2

- Acharya, Baburam (March 1, 1973) [1966], "Annexation Of The Malla Kingdoms" (PDF), Regmi Research Series, 5 (3): 54–60

- Regmi, Mahesh Chandra (August 1, 1973a), "Interviews With Baburam Acharya" (PDF), Regmi Research Series, 5 (8): 141–147

- Regmi, Mahesh Chandra (December 1, 1973b), "Interviews With Baburam Acharya" (PDF), Regmi Research Series, 5 (12): 221–228

- Regmi, Mahesh Chandra (May 1, 1975a), "Preliminary Notes on the Nature of Rana Law and Government" (PDF), Regmi Research Series, 7 (5): 88–97

- Acharya, Baburam (September 1, 1975a), "Social Changes during the Early Shah Period" (PDF), Regmi Research Series, 7 (9): 165–172

- Acharya, Baburam (October 1, 1975b), "Social Changes during the Early Shah Period" (PDF), Regmi Research Series, 7 (9): 184–188

- Regmi, Mahesh Chandra (December 1, 1975b), "Miscellaneous Documents on the Bheri-Mahakali Region" (PDF), Regmi Research Series, 7 (12): 221–223

- Vajracharya, Dhanavajra (December 1, 1975), "Notes on the Changunarayan Inscription" (PDF), Regmi Research Series, 7 (12): 232–240

- Regmi, Mahesh Chandra (May 1, 1976), "The Muluki Ain" (PDF), Regmi Research Series, 8 (5): 81–93

- Acharya, Baburam (September 1, 1976a), "King Prithvi Narayan Shah" (PDF), Regmi Research Series, 8 (9): 172–179

- Acharya, Baburam (December 1, 1976b), "King Prithvi Narayan Shah" (PDF), Regmi Research Series, 8 (12): 225–233

- Wright, Daniel (1877), History of Nepal, Cambridge University Press

- Whelpton, John (2005). A History of Nepal. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-80470-1.

- Hitchcock, John T (1978). "An Additional Perspective on the Nepali Caste System". In James F. Fisher (ed.). Himalayan Anthropology: The Indo-Tibetan Interface. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-90-279-7700-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sharma, Prayag Raj (2004). The State and Society in Nepal: Historical Foundations and Contemporary Trends. Himal Books. ISBN 9789993343622.

- Todd, James (1950). Annals and antiquities of Rajasthan. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- D.R. Regmi (1961), Modern Nepal, Calcutta: Firma K.L. Mukhopadhyay

- Hamilton, Francis Buchanan (1819), An Account of the Kingdom of Nepal, and the Territories Annexed to this Dominion by the House of Gorkha, A Constable

- Gurung, Ganeshman (1994), Indigenous Peoples: Mobilization and Change, S. Gurung

- Rahul, Ram (1996). Royal Nepal: a political history. Vikas publishing house. ISBN 9788125900702.

- Pandey, Ram Niwas (1997). Making of Modern Nepal: A Study of History, Art, and Culture of the Principalities of Western Nepal. Nirala Publications. ISBN 9788185693378.