Radio broadcasting in Australia

The history of broadcasting in Australia has been shaped for over a century by the problem of communication across long distances, coupled with a strong base in a wealthy society with a deep taste for aural communications in a silent landscape.[1] Australia developed its own system, through its own engineers, manufacturers, retailers, newspapers, entertainment services, and news agencies. The government set up the first radio system, and business interests marginalized the hobbyists and amateurs. The Labor Party was especially interested in radio because it allowed them to bypass the newspapers, which were mostly controlled by the opposition. Both parties agreed on the need for a national system, and in 1932 set up the Australian Broadcasting Commission, as a government agency that was largely separate from political interference.

The first commercial broadcasters, originally known as "B" class stations were on the air as early as 1925. Many were sponsored by newspapers in Australia,[2] by theatrical interests, by amateur radio enthusiasts and radio retailers, and by retailers generally.[3] Almost all Australians were within reach of a station by the 1930s, and the number of stations remained relatively stable through the post-war era. However, in the 1970s, the Labor government under Prime Minister Gough Whitlam commenced a broadcasting renaissance so that by the 1990s there were 50 different radio services available for groups based on tastes, languages, religion, or geography.[4] The broadcasting system was largely deregulated in 1992, except that there were limits on foreign ownership and on monopolistic control. By 2000, 99 percent of Australians owned at least one television set, and averaged 20 hours a week watching it.[5]

Programming

Most Australian stations originally broadcast music interspersed with such things as talks, coverage of sporting events, church broadcasts, weather, news and time signals of various types. Virtually all stations also had programs of interest to women, and children's sessions. From the outset, A Class stations' peak-hour evening programs often consisted of live broadcasts from various theatres, including concerts dramas, operas, musicals, variety shows, and vaudeville. The first dramas especially written for radio were heard in the mid-1920s.

The standard accent used by actors and announcers was "Southern English", an upper-class British version that emulated the BBC. The actual Australian accent was acceptable only in low comedy, as in the long-running "Dad and Dave from Snake Gully" program.[6]

By the 1930s, the ABC was transmitting a number of British programs sourced from the BBC, and commercial stations were receiving a number of US programs, particularly dramas. However, in the 1940s, war-time restrictions made it difficult to access overseas programs and, therefore, the amount of Australian dramatic material increased. As well as using original ideas and scripts, there were a number of local versions of overseas programs.

Initially, much of the music broadcast in Australia was from live studio concerts. However, the amount of gramophone (and piano roll) music soon increased dramatically, particularly on commercial stations.

In the late 1930s, the number of big production variety shows multiplied significantly, particularly on the two major commercial networks, Macquarie and Major. After World War II the independent Colgate-Palmolive radio production unit was formed. It poached most major radio stars from the various stations.

Family audiences

Until the 1950s, the whole family seated around a set in the living room was the typical way of listening to radio. Stations tried to be all things to all people, and specialised programming was not really thought about at this stage (it did not come in until the late 1950s). Because of this, programming on most stations was pretty much the same.

In the immediate post-war period, commercial stations typically had a schedule that looked something like this: a breakfast session with bright music including band music, news and weather, a children's segment and, usually, an exercise segment; morning programs were aimed at women listeners, often with large blocks of soap operas or serials, and many segments of the handy hints genre; afternoon programs were also usually geared at women but with more music and, often, a request session; after school, there was inevitably a Children's Session (often hosted by an aunt or uncle or both), and usually featuring birthday greetings; this was followed by another block of serials, often geared at children, and/or dinner music; the major news bulletin was usually at 7.00 pm, often followed by a news commentary; the peak listening hours typically consisted of a mix of variety programs (including many quizzes), dramas, talent quests and the occasional musical program, often live; late night programming mainly consisted of relaxing music, usually mellow jazz or light classical. There was usually only one station in each capital city that was licensed to broadcast through the night.

Children

In children's programming, Ambrose Saunders (1895–1953) was a leading actor. A baritone, He became "Uncle George", telling bedtime stories at first. In 1926 he was joined by his foil Arthur Hahn as 'Bimbo'. In 1927 they moved to 2GB, a pioneer commercial stations. Storytelling was the main ingredient, accompanied by birthday calls, call-out greetings to listeners, songs, and things to make and do. Story-telling remained Saunders' signature role until he retired from radio in 1940.[7]

Sports

Cricket became the major Australian sport in the 1930s, and radio played its part, especially when its broadcast of the test matches with England swelled national pride.[8]

Johnny Moyes, (1893–1963), a veteran newspaper journalist, by 1955 was a leading cricket broadcaster. His biographer notes that his "pithy and authoritative commentaries, delivered in a 'dryly-humourous voice', won thousands of listeners to the A.B.C. He was renowned for his summaries of the day's game which, he wrote, should be 'factual and yet not dull'". His 'infectiously hysterical' description of the last over of the tied Test between Australia and the West Indies in 1960 became an iconic statement of broadcast journalism at its most entertaining.[9]

Cyril Angles, (1906–1962), a former jockey, began broadcasting horse races in 1931 over station 2KY. He called from 30 to 60 races every week, some 30,000 during his career, as well as commenting on many other sporting events. His biographer notes that, "The accuracy of his incisive and unhurried descriptions, delivered in a flat, mechanical and slightly abrasive voice, established his reputation." He became the best-paid sportscaster in Australia.[10]

Religion

Religious programs were widely broadcast, with an emphasis on religious services, sermons, and church music. One of the most popular programs from 1931 to 1968 was "Dr. Rumble's Question Box." Rumble, a Catholic priest, gave advice by answering letters from listeners about life's problems for an hour every Sunday night. Frank Sturge Harty broadcast a similar program every afternoon from an Anglican perspective.[11]

Trouble arose in 1931 when the Jehovah's Witnesses took control of station 5KA. In 1933 the government banned its diatribes against the Catholic Church, the British Empire, and the United States. In 1941 its station was closed down as dangerous to national security, at the demand of the Army and Navy. Furthermore, the Jehovah's Witnesses were declared an illegal organization.[12]

The 1950s and 1960s

Like most of the world, Australia experienced great changes to broadcasting during the 1950s and 1960s. This was mainly caused by two things: the introduction of television and the gradual replacement of the radio valve with the transistor.

Mainstream television transmission commenced in Sydney and Melbourne just in time for the Melbourne Olympic Games in November/December 1956. It was then phased in at other capital cities, and then into rural markets. Many forms of entertainment, particularly drama and variety, proved more suited to television than radio, so the actors and producers migrated there.

The transistor radio first appeared on the market in 1954. In particular, it made portable radios even more transportable. All sets quickly became smaller, cheaper and more convenient. The aim of radio manufacturers became a radio in every room, in the car, and in the pocket.

The upshot of these two changes was that stations started to specialise and concentrate on specific markets. The first areas to see specialised stations were the news and current affairs market, and stations specialising in pop music and geared toward the younger listener who was now able to afford his/her own radio.

Talkback was to become a major radio genre by the end of the 1960s, but it was not legalised in Australia until October 1967.[14] The fears of intrusion were addressed by a beep that occurred every few seconds, so that the caller knew that his/her call was being broadcast. There was also a seven-second delay so that obscene or libelous material could be monitored.

By the end of the 1960s, specialisation by radio stations had increased dramatically and there were stations focusing on various kinds of music, talkback, news, sport, etc.

The 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s

After much procrastination on the part of various federal governments, FM broadcasting was eventually introduced in 1975. (There had been official experiments with FM broadcasting as far back as 1948.)

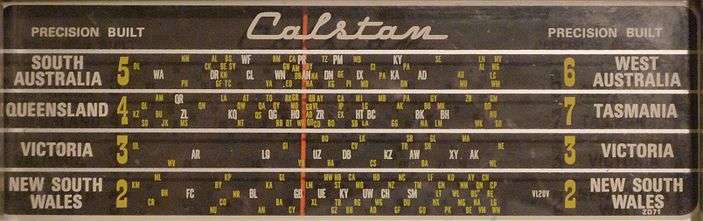

Only a handful of radio stations were given new licences during the 1940s, 1950s & 1960s but, since 1975, many hundreds of new broadcasting licences have been issued on both the FM and AM bands. In the latter case, this was made possible by having 9 kHz between stations, rather than 10 kHz breaks, as per the Geneva Frequency Plan. The installation of directional aerials also encouraged more AM stations.

.svg.png)

The types of station given FM licences reflects the policies and philosophies of the various Australian governments. Initially, only the ABC and community radio stations were granted FM licences. However, after a change of government, commercial stations were permitted on the band, as from 1980. At first, one or two brand new stations were permitted in each major market. However, in 1990, one or two existing AM stations in each major market were given FM licences; the stations being chosen by an auction system. Apart from an initial settling-in period for those few stations transferred from AM to FM, there has been no simulcasting between AM and FM stations.

In major cities, a number of brand new FM licences were issued in the 1990s and 2000s. All rural regions which traditionally had only one commercial station now have at least one AM and one FM commercial station. In many cases, the owner of the original station now has at least two outlets. The number of regional transmitters for the ABC's five networks also increased dramatically during this era.

The 2000s

From August 2009, digital radio was phased in by geographical region. Today, the ABC, SBS, commercial and community radio stations operate on the AM and FM bands. Most stations are available on the internet and most also have digital outlets. By 2007, there were 261 commercial stations in Australia.[14] The ABC currently has five AM/FM networks and is in the process of establishing a series of supplementary music stations that are only available on digital radios and digital television sets. SBS provides non-English language programs over its two networks, as do a number of community radio stations.

Political issues

Dual system

Australia faced the choice between the American system of privately owned radio stations with minimal government control, favoured by the Liberal Party, or a government run system as exemplified by the British BBC, favoured by the Labor Party. The result was a compromise and Australia's dual radio broadcasting system comprises two parts.

The "Public" sector (Class A stations), operated by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC), which is modeled after the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). This sector was originally funded by listener licence fees. However, all licence fees were abolished in 1974 by the Australian Labor Party government led by Gough Whitlam on the basis that the near-universality of television and radio services meant that public funding was a fairer method of providing revenue for government-owned radio and television broadcasters. The ABC since then has been funded by government grants, plus its own commercial activities (merchandising, overseas sale of programmes, etc.)

The "Commercial" sector (Class B stations) consists of privately owned radio stations, which may operate within "Networks". The two major, early commercial networks, Macquarie and Major were modeled after the American system and funded through advertising revenue. By 2007, there were 261 commercial radio stations.[15][16]

Politics on the air

Both Labor and Liberal politicians who visited the United States were highly impressed with the rapidly growing importance of political broadcasts. The 1931 national election was the first to feature heavy use of political broadcasts. Labor Prime Minister James Scullin was in a difficult contest, and he realized that radio receivers were now widespread, and the medium was much more effective and much cheaper than stumping in person using long-distance train travel. The New South Wales Labor Party leader Jack Lang emulated President Roosevelt's "fireside chat" format. Liberals followed suit; Robert Menzies based his 1949 Liberal campaign around radio broadcasts.[17][18]

During the Second World War, Prime Minister Curtin made very heavy use of newspapers and broadcast media, especially through press conferences, speeches, and newsreels. Australians gained a sense it was a people's war in which they were full participants.[19]

After numerous short-lived experiments in the states, Parliament began radio broadcasts of its proceedings in 1946.[20] Live television broadcasts of selected parliamentary sessions started in 1990. ABC NewsRadio, a continuous news network broadcast on the Parliamentary and News Network when parliament is not sitting, was launched on 5 October 1994.[21]

In sharp contrast to print media, television broadcasts offered critical accounts of Australia's role in the war in Vietnam. In particular, the program "Four Corners favoured the viewpoint of the antiwar and anticonscription movements.[22]

Political scientists have suggested that television coverage has subtly transformed the political system, with a spotlight on leaders rather than parties, thereby making for more of an American-presidential-style system. In the 2001 Federal election, television news focused on international issues, especially terrorism and asylum seekers. The September 11 attacks three weeks earlier had dominated the news. Minor parties were largely ignored as the two main parties monopolized the camera's attention. The election was depicted as a horse race between the Coalition's John Howard, who ran ahead and was therefore given more coverage than his Labor rival Kim Beazley.[23]

International issues

Australians were not satisfied with rebroadcast BBC material; they took too much pride in their own original programming as compared to BBC's mediocre "Empire Service".[24] Furthermore, Australia had its own worldwide shortwave service called "The Voice of Australia" 1931 to 1939. When war broke out the government set up "Radio Australia" to disseminate propaganda and the Allied version of war news throughout the South Pacific.[25]

Pop Americana versus British heritage

In Australia's media world, there was a subtle cultural war underway between the pull of American popular culture on the one hand, with its widespread popularity and the risk according to its critics, of degrading the public taste. Critics favoured the supposedly superior traditional culture of the mother country, which appealed to upscale audiences that were representative of the nation's elite. Richard Boyer (1891–1961), chairman of the Australian Broadcasting Commission, fought against commercialism because he feared it would lead to American dominance. He held that the BBC model of a publicly owned and operated television would sustain Australia's British heritage.[26]

Multiculturalism

The arrival of large numbers of new immigrants after 1945, along with a radical revision of attitudes toward nonwhite groups, produced pressures on the government regarding broadcasting access. Demands led to the creation of the Special Broadcasting Service, a publicly funded broadcaster mandated to provide multicultural and multilingual programming. In Canada, by contrast, the government stood apart and multicultural or multilingual program was provided by the private sector.[27][28]

Since 1968, aborigines have controlled Imparja Television, a network based in Alice Springs.[29] The Central Australian Aboriginal Media Association, founded in 1980 by Freda Glynn (b. 1939), produces radio and television programs aimed at Aboriginal communities from a base in Alice Springs.[30]

In 1976 the Green Inquiry created the Australian Broadcasting Tribunal. It opened up licence renewal hearings to the public, giving voice to those with sharp criticisms of Australian broadcasting.[31]

Television

As early as 1929, two Melbourne commercial radio stations, 3UZ and 3DB were conducting experimental mechanical television broadcasts – these were conducted in the early hours of the morning, after the stations had officially closed down. In 1934 Dr Val McDowall[32] at amateur station 4CM Brisbane[33] conducted experiments in electronic television.

Television broadcasting officially began in 1956 and has since expanded to include a broad range of public, commercial, community, subscription, narrowcast, and amateur stations across the country. Colour television in the PAL 625-line format went to a full-time basis in 1975. Subscription television, on the Galaxy platform, began in 1995. Digital terrestrial television was introduced in 2001.[34]

ABC: The national system

The Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC), established in 1929, is Australia's state-owned and funded national public broadcaster. With a total annual budget of A$1.22 billion,[35] the corporation provides television, radio, online and mobile services throughout metropolitan and regional Australia, as well as overseas through the Australia Network and Radio Australia and is well regarded for quality and reliability as well as for offering educational and cultural programming that the commercial sector would be unlikely to supply on its own.[36]

1920s–40s

The first public radio station in Australia opened in Sydney on 23 November 1923 under the call sign 2SB with other stations in Melbourne, Brisbane, Adelaide, Perth and Hobart following.[37] A licensing scheme, administered by the Postmaster-General's Department, was soon established allowing certain stations government funding, albeit with restrictions placed on their advertising content.[38]

Following a 1927 royal commission inquiry into radio licensing issues, the government established the National Broadcasting Service which subsequently took over a number of the larger funded stations. It also nationalised the Australian Broadcasting Company which had been created by entertainment interests to supply programs to various radio stations.[38] On 1 July 1932, the Australian Broadcasting Commission was established, taking over the operations of the National Broadcasting Service and eventually establishing offices in each of Australia's capital cities.[38][39]

Over the next four years the stations were reformed into a cohesive broadcasting organisation through regular program relays, coordinated by a centralised bureaucracy.[40] The Australian broadcast radio spectrum was constituted of the ABC and the commercial sector.[40]

Cater argues that reform was urgently needed in 1945:

- By the end of World War II, the ABC was a decadent, hollow institution. Its authority had been compromised by a poorly drafted charter and further undermined by timid management, poor governance and creeping wartime censorship. In April 1945, Boyer refused to accept the post of chairman until Prime Minister Curtin issued a mandate of independence which Boyer drafted himself. The ABC under Boyer and general manager Charles Moses invested as best it could in the cultural capital of the nation, establishing viable symphony orchestras and seizing on the potential of television.... [Boyer's] neutrality was never seriously questioned.[41]

1950s–70s

The ABC began television broadcasting in 1956 ABN-2 (New South Wales) Sydney was inaugurated by Prime Minister Robert Menzies on 5 November 1956.[42] ABV-2. Broadcasting big-band and other major cities 1956–1961. Television relay facilities were put in place in the early 1960s. Until then, news bulletins were sent to each TV station. Popular programs at the time included Six O'Clock Rock hosted by Johnny O'Keefe, Mr. Squiggle, as well as operas and plays. Rugby was first broadcast in 1973. Colour was introduced in 1975. ABC budget cuts began in 1976 and continued until 1985, leading to some short strikes. The budget cuts crippled the network for years."[43]

Many Australian households quickly rearranged their dining habits so the family could watch television together at tea time. The lounge typically became the TV room. Magazines published advice on preparing meals to be taken in front of the television. Stores began to carry new products such as vinyl furniture, frozen dinners, tray tables, and plastic dishes.[44]

1980s–90s

Starting with its new name in 1983, the "Australian Broadcasting Corporation" underwent significant restructuring. The ABC was split into separate television and radio divisions, with an overhaul of management, finance, property and engineering.[45] Program production was expanded in indigenous affairs, comedy, drama, social history and current affairs. Local production trebled from 1986 to 1991 with the assistance of co-production, co-financing, and pre-sales arrangements.[45]

A new Concert Music Department was formed in 1985 to coordinate the corporation's six symphony orchestras, which in turn received a greater level of autonomy to better respond to local needs.[45] Open-air free concerts and tours, educational activities, and joint ventures with other music groups were undertaken at the time to expand the orchestras' audience reach.[45]

ABC Radio was restructured significantly again in 1985 – Radio One became the Metropolitan network, while Radio 2 became known as Radio National (callsigns, however, were not standardised until 1990). New programs such as The World Today, Australia All Over, and The Coodabeen Champions were introduced, while ABC-FM established an Australian Music Unit in 1989.[45] Radio Australia began to focus on the Asia-Pacific region, with coverage targeted at the south west and central Pacific, south-east Asia, and north Asia. Radio Australia also carried more news coverage, with special broadcasts during the 1987 Fijian coup, Tiananmen Square massacre, and the First Gulf War.[45]

The ABC Multimedia Unit was established in July 1995, to manage the new ABC website (launched in August). Funding was allocated later that year specifically for online content, as opposed to reliance on funding for television and radio content. The first online election coverage was put together in 1996, and included news, electorate maps, candidate information and live results. By the early 1990s, all major ABC broadcasting outlets moved to 24-hour-a-day operation, while regional radio coverage in Australia was extended with 80 new transmitters.[46]

International television service Australia Television International was established in 1993, while at the same time Radio Australia increased its international reach. Reduced funding in 1997 for Radio Australia resulted in staff and programming cuts.

Australia Television was sold to the Seven Network in 1998; however, the service continued to show ABC news and current affairs programming up until its closure in 2001.[47] The ABC's television operation joined its radio and online divisions at the corporation's Ultimo headquarters in 2000.[48]

2000s

In 2001, digital television commenced after four years of preparation.[48] In readiness, the ABC had fully digitised its production, post-production and transmission facilities. The ABC's Multimedia division was renamed "ABC New Media", becoming an output division of the ABC alongside Television and Radio.[48] Legislation allowed the ABC to provide 'multichannels' – additional, digital-only, television services managed by the New Media Division. Soon after the introduction of digital television in 2001, Fly TV and the ABC Kids channel launched, showing a mix of programming aimed at teenagers and children.

In 2002, the ABC launched ABC Asia Pacific – the replacement for the defunct Australia Television International operated previously by the Seven Network. Much like its predecessor, and companion radio network Radio Australia, the service provided a mix of programming targeted at audiences throughout the Asia-Pacific region. Funding cuts in 2003 led to the closure of Fly TV and the ABC Kids channel.

The ABC launched a digital radio service, ABC DiG, in November 2002, available through the internet and digital television, but not available through any other terrestrial broadcast until DAB+ became available in 2009.

ABC2, a second attempt at a digital-only television channel, was launched on 7 March 2005. By 2006 ABC2 carried comedy, drama, national news, sport and entertainment.[49]

2010s

ABC News 24 launched on 22 July 2010,[50] and brought with it both new programming content as well as a collaboration of existing news and current affair productions and resources. The ABC launched the 24-hour news channel to both complement its existing 24-hour ABC News Radio service and compete with commercial offerings on cable TV. It became the ABC's fifth domestic TV channel and the fourth launched within the past 10 years.

Related Wikipedia Articles

Australia

- Amalgamated Wireless (Australasia) (the ubiquitous company with major impact upon the first five decades of broadcasting in Australia)

- Call signs in Australia (comprehensive discussion of callsigns for all services, structure a little confusing)

- Australian Broadcasting Company (best known as the contractor for provision of programming to the National Broadcasting Service 1929-1932)

- Australian Broadcasting Corporation (overview of our national broadcaster, mostly current, minimal history)

- History of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (more detailed history of the ABC)

- List of Australian AM radio stations (still a work in progress but records the many frequency changes for AM services over a century)

- List of people in communications and media in Australia (former section of this article)

- List of radio stations in Australia (comprehensive, mostly current services, but some historical, includes AM, FM, Digital, Narrowcast)

- Media of Australia (brief overview only, another work in progress)

- Newspapers in Australia (brief overview only, another work in progress)

- Television broadcasting in Australia (comprehensive overview of current licensing & systems, minimal technology/history/development)

- Timeline of Australian radio (many errors and much trivia given prominence, but also much potential)

International / Technology

- History of broadcasting

- History of radio

- History of telecommunication (excellent polished discussion of all communications technology categories)

- History of television (excellent discussion of the technology, no material yet about Australia)

- Invention of radio

- Wireless telegraphy (discussion of the three types of "Telegraphy without Wires")

Programs

- Argonauts Club, the ABC's iconic children's session

- Australia's Amateur Hour

- Blue Hills, radio serial

- Boyer Lectures, annual ABC series of prestige lectures

- The Castlereagh Line, radio serial

- Carols by Candlelight, annual presentation originally organised for broadcasting

- Consider Your Verdict, radio drama (later TV drama)

- Football Inquest, Melbourne-based Australian rules football program

- D24, radio drama

- Dad and Dave, radio comedy/drama serial

- Give it a Go, quiz program

- Information Please, refer to Overseas section

- It Pays to Be Funny, quiz program

- Meet the Press, political interview program

- Music for Pleasure, ABC classical music program

- One Man's Family, refer to Overseas section

- The Oxford Show, variety program

- Pick a Box, quiz program

- Quiz Kids, Australian version of a US panel show

- The Pressure Pak Show, quiz program

- Singers of Renown, ABC program featuring classical singers

- When a Girl Marries, refer to Overseas section

- Yes, What?, radio comedy series

In-line citations

- Diane Collins, "Acoustic journeys: exploration and the search for an aural history of Australia". Australian Historical Studies 37.128 (2006) pp: 1–17 online

- Denis Cryle, "The press and public service broadcasting: Neville Petersen's news not views and the case for Australian exceptionalism." (2014) Media International Australia, Incorporating Culture & Policy Issue 151 (May 2014): 56+.

- R.R. Walker, The Magic Spark – 50 Years of Radio in Australia (1973).

- John Potts, Radio in Australia (1986)

- Graeme Davison et al., eds., The Oxford Companion to Australian History (2001), pp 546–47, 637–38

- John Rickard, Australia: A Cultural History (1988) p. 141

- Jan Brazier, 'Saunders, Ambrose George Thomas (1895–1953)', Australian Dictionary of Biography (1988) v.11; accessed 14 May 2015.

- Frazer Andrewes, "'They Play in Your Home': Cricket, Media and Modernity in Pre-War Australia", International Journal of the History of Sport (2000) 17#2–3 pp: 93–110.

- Anne O'Brien, 'Moyes, Alban George (Johnny) (1893–1963)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, (2000) v 15; accessed online 14 May 2015

- John Ritchie, 'Angles, Cyril Joseph (1906–1962)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, (1993) v 13; accessed online 14 May 2015

- Bridget Griffen-Foley, "Radio Ministries: Religion on Australian Commercial Radio from the 1920s to the 1960s", Journal of Religious History (2008) 32#1 pp: 31–54. online

- Peter Strawhan, "The closure of radio 5KA, January 1941". Australian Historical Studies 21.85 (1985) pp: 550–564. online

- Diane Langmore (2007). Australian Dictionary of Biography, 1981–1990. The Miegunyah Press. pp. 56–57. ISBN 9780522853827.

- Changing Stations – The Story of Australian Commercial Radio, Bridget Griffen-Foley, Sydney, 2009

- Griffen-Foley, Bridget (2010). "Australian Commercial Radio, American Influences—and The BBC". Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television. 30 (3): 337–355. doi:10.1080/01439685.2010.505034.

- Greg Mundy, "'Free-Enterprise' or 'Public Service'? The Origins of Broadcasting in the U.S., U.K. and Australia", Australian & New Zealand Journal of Sociology (1982) 18#3 pp: 279–301

- Ian Ward, "The early use of radio for political communication in Australia and Canada: John Henry Austral, Mr Sage and the Man from Mars", Australian Journal of Politics & History (1999) 45#3 pp 311–30. online

- Richardson, Nick (2010). "The 1931 Australian Federal Election—Radio Makes History". Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television. 30 (3): 377–389. doi:10.1080/01439685.2010.505037.

- Caryn Coatney, "John Curtin's Forgotten Media Legacy: The Impact of a Wartime Prime Minister on News Management Techniques, 1941–45", Labour History (2013), Issue 105, pp 63–78. online

- Ian Ward, "Parliament on 'the Wireless' in Australia", Australian Journal of Politics & History (2014) 60$2 pp 157–176.

- Sally Young, "Political and parliamentary speech in Australia". Parliamentary Affairs (2007) 60#2 pp: 234–252.

- Gorman, Lyn (1997). "Television and War: Australia's Four Corners Programme and Vietnam, 1963–1975". War & Society. 15 (1): 119–150. doi:10.1179/war.1997.15.1.119.

- David Denemark, Ian Ward, and Clive Bean, Election Campaigns and Television News Coverage: The Case of the 2001 Australian Election. Australian Journal of Political Science. (2007) 42#1 pp: 89–109 online

- Simon J. Potter, "Who listened when London called? Reactions to the BBC empire service in Canada, Australia and New Zealand, 1932–1939", Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television (2008) 28#4 pp: 475–487

- Errol Hodge, "Radio Australia in the Second World War", Australian Journal of International Affairs (1992) 46#2 pp: 93–108 online

- Simon J. Potter, "'INVASION BY THE MONSTER' Transnational influences on the establishment of ABC Television, 1945–1956". Media History (2011) 17#3 pp: 253–271.

- Patterson, Rosalind (1999). "Two Nations, Many Cultures: the Development of Multicultural Broadcasting in Australia and Canada". International Journal of Canadian Studies/ Revue Internationale d'Études Canadiennes. 19: 61–84.

- Patterson, R. (1990). "Development of Ethnic and Multicultural Media in Australia". International Migration. 28 (1): 89–103. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2435.1990.tb00137.x.

- Michael Meadows and Helen Molnar. "Bridging the gaps: Towards a history of indigenous media in Australia". Media History (2002) 8#1 pp: 9–20.

- Julie Wells, "Interview with Freda Glynn". Lilith (1986), Issue 3, pp. 26–44.

- Deborah Haskell, "The Struggle for Accountability in Australian Broadcasting 1979". International Communication Gazette (1980) 26#2 pp. 65–87.

- https://www.racp.edu.au/page/library/college-roll/college-roll-detail&id=496 Archived 4 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- https://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:212637/s00855804_1961_1962_6_4_750.pdf,

- Albert Moran and Chris Keating. The A to Z of Australian Radio and Television (Scarecrow Press, 2009)

- Retrieved 4 December 2013 Budget Paper No. 4 2012–2013

- Brian McNair and Adam Swift (18 March 2014). "What would the Australian media look like without the ABC?". The Conversation. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- "Celebrating 100 Years of Radio – History of ABC Radio". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 3 October 2007.

- Langdon, Jeff (1996). "The History of Radio in Australia". Radio 5UV. Archived from the original on 3 March 2004. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- "ABC celebrates 80 years of broadcasting". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 1 July 2012. Retrieved 1 July 2012.

- "Australian Broadcast History". Barry Mishkid. Archived from the original on 25 October 2007. Retrieved 3 October 2007.

- Nick Cater, The Lucky Culture and the Rise of an Australian Ruling Class (2013) p 201

- Australian Broadcasting Corporation, "About the ABC: History of the ABC: James Dibble". Retrieved 3 September 2008.

- Molomby, Tom, Is there a moderate on the roof? ABC Years, William Heinemann Australia, Port Melbourne, 1991, p.160

- Groves, Derham (2004). "Gob Smacked! TV Dining in Australia Between 1956 and 1966". Journal of Popular Culture. 37 (3): 409–417. doi:10.1111/j.0022-3840.2004.00076.x.

- "About the ABC – The 80s". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 8 December 2012. Retrieved 1 October 2007.

- "About the ABC – The 90s". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 6 December 2012. Retrieved 1 October 2007.

- "2UE; Australian Television International". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. March 2001. Retrieved 25 September 2007.

- "About the ABC – 2000s – A New Century". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 9 December 2012. Retrieved 1 October 2007.

- Day, Julia (18 October 2006). "Australia opens up media investment". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 31 March 2007.

- "ABC to launch 24h news channel". Australia: ABC. Retrieved 16 May 2010.

Further reading

Books, theses & major articles

- Crawford, Robert. But wait, there's more...: a history of Australian advertising, 1900–2000 (Melbourne Univ. Press, 2008)

- Cunningham, Stuart, and Graeme Turner, eds. The Media & Communications in Australia (2nd ed. 2010) online

- Elliot, Hugh. "The Three-Way Struggle of Press, Radio and TV in Australia". Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly (1960) 37#2 pp: 267–274.

- Griffen-Foley, Bridget. Changing Stations the story of Australian commercial radio

- Griffen-Foley, Bridget. "Australian Commercial Radio, American Influences—and The BBC". Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television (2010) 30#3 pp: 337–355. online

- Griffen‐Foley, Bridget. "From the Murrumbidgee to Mamma Lena: Foreign language broadcasting on Australian commercial radio, part I". Journal of Australian Studies 2006; 30(88): 51–60. part 1 online; part 2 online

- Harte, Bernard. When Radio Was The Cat's Whiskers (Rosenberg Publishing, 2002)

- Inglis, K. S. This is the ABC – the Australian Broadcasting Commission 1932–1983 (2006)

- Inglis, K. S. Whose ABC? The Australian Broadcasting Corporation 1983–2006 (2006)

- Johnson, Lesley. The Unseen Voice: a cultural study of early Australian radio (London, 1988)

- Jolly, Rhonda. Media ownership and regulation: a chronology (Canberra, 2016)

- Jones, Colin. Something in the air : a history of radio in Australia (Kenthurst, 1995)

- Kent, Jacqueline. Out of the Bakelite Box: the heyday of Australian radio (Sydney, 1983)

- Mackay, Ian K. Broadcasting in Australia (Melbourne University Press, 1957)

- Martin, Fiona (2002). "Beyond public service broadcasting? ABC online and the user/citizen". Southern Review: Communication, Politics & Culture. 35 (1): 42.

- Moran, Albert, and Chris Keating. The A to Z of Australian Radio and Television (Scarecrow Press, 2009)

- Petersen, Neville. News Not Views: The ABC, Press and Politics (1932–1947) (Sydney, 1993), Emphasizes newspaper restrictions on broadcasters

- Potter, Simon J. "‘Invasion by the Monster’ Transnational influences on the establishment of ABC Television, 1945–1956". Media History (2011) 17#3 pp: 253–271.

- Potts, John. Radio in Australia (UNSW Press, 1989)

- Semmler, Clement. The ABC: Aunt Sally and Sacred Cow (1981)

- Thomas, Alan. Broadcast and Be Damned, The ABC's First Two Decades (Melbourne University Press, 1980)

- Walker, R. R. The Magic Spark: 50 Years of Radio in Australia (Hawthorn Press, 1973)

- Ward, Ian (1999). "The early use of radio for political communication in Australia and Canada: John Henry Austral, Mr Sage and the Man from Mars". Australian Journal of Politics & History. 45 (3): 311–330. doi:10.1111/1467-8497.00067.

- Young, Sally (2003). "A century of political communication in Australia, 1901–2001". Journal of Australian Studies. 27 (78): 97–110. doi:10.1080/14443050309387874.

Regulatory

Oversight Department

- Australia, Postmaster-General's Department. "Annual Reports 1910–1975" NLA

- Australia, Department of the Media. "Annual Reports 1973–1976" NLA

- Australia, Postal and Telecommunications Department. "Annual Reports 1978–1980" NLA

- Australia, Department of Communications (1). "Annual Reports 1981–1987" NLA

- Australia, Department of Transport and Communications. "Annual Reports 1988–1993" NLA

- Australia, Department of Communications (2)

- Australia, Department of Communications and the Arts. "Annual Reports 1994–1998" NLA

- Australia, Department of Communications, Information Technology and the Arts. "Annual Reports 1999–2007" NLA

- Australia, Department of Broadband, Communications and the Digital Economy. "Annual Reports 2008–2013" NLA

- Australia, Department of Communications (3). "Annual Reports 2014–2015" NLA

- Australia, Department of Communications and the Arts (2). "Annual Reports 1999–2007" NLA

Subordinate Agencies

- Australian Broadcasting Control Board. "Annual Reports 1949–1976" NLA online

- Overseas Telecommunications Commission (Australia). "Annual Reports". 1965–1973 NLA 1974–1981 NLA 1982–1984 NLA 1985–1991 NLA

- Australian Telecommunications Commission T/as Telecom Australia. "Annual Reports". 1976–1991 NLA 1993 – present NLA

- Australian Broadcasting Tribunal. "Annual Reports 1977–1992" NLA online

- Australian Telecommunications Authority T/as AusTel. "Annual Reports 1990–1997". NLA

- Australian and Overseas Telecommunications Corporation. "Annual Reports" 1992 NLA

- Australian Broadcasting Authority. "Annual Reports 1993–2005" NLA

- Australia, National Transmission Agency. "Annual Reports 1993–1996" NLA

- Australia, Spectrum Management Agency. "Annual Reports 1994–1997" NLA

- Australia, National Transmission Authority. "Annual Reports 1997–1999"

- Australian Communications Authority. "Annual Reports 1998–2005" NLA

- Australian Communications and Media Authority. "Annual Reports 2006–present" NLA

Broadcasters

- Australian Broadcasting Commission. "Annual Reports 1933–1983" NLA

- Australian Broadcasting Corporation. "Annual Reports 1984–present" NLA

- Special Broadcasting Service. "Annual Reports 1979–1991" NLA

- Special Broadcasting Service Corporation. "Annual Reports 1992–present" NLA

Related Government

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. "Year Book Australia 1908-2012" online 1908 has material back to Federation, refer Transport & Communications