Radamisto (Handel)

Radamisto (HWV 12) is an opera seria in three acts by George Frideric Handel to an Italian libretto by Nicola Francesco Haym, based on L'amor tirannico, o Zenobia by Domenico Lalli and Zenobia by Matteo Noris. It was Handel's first opera for the Royal Academy of Music. The opera's plot is loosely based on incidents from Tacitus's Annals of Imperial Rome.

Performance history

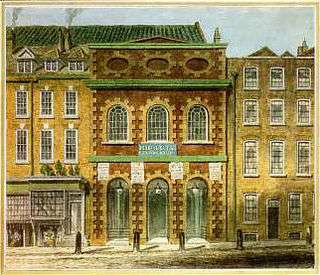

It was first performed at the King's Theatre, London on 27 April 1720, a performance attended by King George I and his son, the Prince of Wales,[1] and was judged to be a success, resulting in 10 further performances. A revised version with different singers including the internationally renowned castrato Senesino in the first of many roles he performed in Handel's works was written for a revival on 28 December 1720. More revisions followed for yet another version presented in 1721. In 1728 Radamisto was again revised for another revival featuring the two famous prima donnas Cuzzoni and Faustina as well as Senesino. The first modern performance was in Göttingen on 27 June 1927.

As with most opere serie, Radamisto went unperformed for many years, but with the revival of interest in Baroque music and historically informed musical performance since the 1960s, Radamisto, like all Handel operas, receives performances at festivals and opera houses today.[2] The first production in the US, in a semi-staged version, took place on 16 February 1980 in Washington, DC and the first fully staged presentation was given by Opera/Chicago in 1984.[3] Among other productions, Radamisto was staged by Santa Fe Opera in 2008, by English National Opera in 2010[4] and by Theater an der Wien in 2013.[5] An acclaimed production of Radamisto (first version) was directed by Sigrid T’Hooft at the Badisches Staatstheater in Karlsruhe, in 2009. Fully conceived in period style (it took its cue from an original prompt book), T'Hooft's staging was revived and now ranks among the most significant examples of historically informed performance in opera.[6]

Roles

| Role | Voice type | Premiere Cast, 27 April 1720 |

Revised version Premiere Cast, 28 December 1720 |

Revised version Premiere Cast, 1728 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radamisto, son of Farasmane |

soprano / alto castrato |

Margherita Durastanti |

Francesco Bernardi, called Senesino | Senesino |

| Zenobia, his wife |

contralto / soprano / soprano |

Anastasia Robinson |

Margherita Durastanti |

Faustina Bordoni |

| Tiridate, King of Armenia |

tenor / bass | Alexander Gordon |

Giuseppe Maria Boschi |

Giuseppe Maria Boschi |

| Polissena, his wife, daughter of Farasmane |

soprano | Ann Turner Robinson |

Maddalena Salvai | Francesca Cuzzoni |

| Farasmane, King of Thrace |

bass | John Lagarde | John Lagarde | Giovanni Battista Palmerini |

| Tigrane, Prince of Pontus |

soprano / soprano castrato / alto castrato |

Caterina Galerati |

Matteo Berselli | Antonio Baldi |

| Fraarte, brother of Tiridate |

soprano castrato / soprano |

Benedetto Baldassari |

Caterina Galerati |

(role cut) |

Synopsis

- Place: Armenia, Temple of Garni

- Time: 53 A.D.

Act 1

In the royal tent outside the city, Polissena, desperately unhappy, prays to the gods to help her in her sorrow ("Sommi Dei"). She is married to Tiridate, King of Armenia, but he has conceived a mad passion for another woman, Zenobia, who is married to Polissena's brother, Prince Radamisto, heir to the throne of the neighbouring kingdom of Thrace. Fraarte, Tiridate's brother, and Tigrane, an ally of Tiridate, come to Polissena and tell her that such is her husband's obsession with his sister-in-law Zenobia that he has declared war on the kingdom and is besieging the city, all so he can satisfy his desire for her. Fraarte and Tigrane advise Queen Polissena to forget about her husband ("Deh! fuggi un traditore") and console herself with Tigrane ("L’ingrato non amar"), who is in love with her, but Polissena is not interested. Tiridate enters and tells his wife to leave; King Farasmane of Thrace, her father, is brought to Tiridate in chains, having been captured in the battle and Tiridate warns he will be put to death unless Zenobia is given to him. Polissena pleads for mercy, but Tiridate dismisses her ("Tu vuoi ch’io parta").

In the camp of Tiridate, Radamisto and Zenobia have come to try to negotiate the release of King Farasmene, Radamisto's father. Tiridate threatens to kill Farasmene unless they surrender the city ("Con la strage de’ nemici"). Radamisto and Zenobia are anguished ("Cara sposa, amato bene"). In order to prevent further bloodshed, Zenobia offers herself to Tiridate ("Son contenta di morire"), leaving Radamisto torn ("Perfido, di a quell'empio tiranno") but Farasmene says he prefers to die rather than live by the sacrifice of his daughter-in-law's honour ("Son lievi le catene").

In front of Tiridate's palace, he is greeted as he returns victorious from the battle. Radamisto and Zenobia have escaped and King Farasmene will be held hostage until they are found. Polissena rebukes her husband Tiridate for his dishonourable behaviour and his adulterous pursuit of his sister-in-law but his only response is to tell her to keep quiet ("Segni di crudeltà"). Tigrane again presses his attentions on her, but Polissena rejects him and can only hope that happier times lie ahead ("Dopo l'orride procelle").

Act 2

In the countryside by the river Araxes, Radamisto and Zenobia are fleeing from Tiridate and his army. Zenobia is at the end of her endurance; Tiridate is waging war and shedding blood all in the attempt to satisfy his lust for her ("Vuol ch’io serva"). It seems to her the best thing would be her death and then his cruelty would cease. She asks her husband to kill her; he tries to stab her as she asks but cannot bring himself to inflict more than a slight wound whereupon she jumps into the river. Radamisto is captured by Tigrane and his men who offer to take him to his sister Polissena. Radamisto is grief-stricken by what he assumes to be his wife's death and prays for peace for her soul ("Ombra cara di mia sposa"). In fact Zenobia has been rescued from drowning by Fraarte; Zenobia is still full of fury towards Tiridate ("Già che morir non posso"), even as Fraarte tries to console her ("Lascia pur amica spene").

In the garden of Tiridate's palace, Zenobia is led in by Fraarte and presented to Tiridate, who still passionately desires her ("Sì che ti renderai"). Her only concern is trying to find out her husband's whereabouts ("Fatemi, oh Cieli, almen"). In fact, Radamisto is now in the same palace, having been brought to his sister Queen Polissena by Tigrane, who is hoping that the conflict can now be resolved ("La sorte, il Ciel amor"). Radamisto wants to assassinate Tiridate but Polissena loves her husband despite everything and refuses to take part in such a plot, leaving Radamisto furious at her faithfulness to a tyrant ("Vanne, sorella ingrata").

Inside the palace, Zenobia is still mourning her fate ("Che farà quest'alma mia") while Tiridate continues to harass her with his desires. Tigrane brings them the false news that Radamisto has died, and presents Radamisto's supposed servant,"Ismeno", really Radamisto himself in disguise, who relates Radamisto's last words. Zenobia recognises her husband's voice, and when the two of them are left alone, she and Radamisto sing of their love for each other ("Se teco vive il cor")

Act 3

Outside the palace, Tigrane and Fraarte agree that Tiridate's monstrous tyranny must be stopped ("S'adopri il braccio armato"). Tigrane, recognising the hopelessness of his love for Polissena, perseveres nonetheless ("So ch'è vana la speranza").

In a room of the palace, Zenobia is concerned that her husband's disguise will be seen through and he seeks to allay her fears ("Dolce bene di quest'alma"). He hides as Tiridate comes in and again attempts to seduce Zenobia. Radamisto emerges from hiding as Polissena and Farasmene also enter, preventing Tiridate from molesting Zenobia, but Farasmane recognises his son Radamisto and calls him by name. Tiridate orders Radamisto to be executed, leaving Radamisto ("Vile! se mi dai vita") and Zenobia outraged at his tyranny ("Barbaro! partirò, ma sdegno poi verrà"). Despite the pleas of his wife Polissena, whose love for her husband is turning to hatred, Tiridate stays firm. Radamisto and Zenobia take a tearful farewell of each other ("Deggio dunque, oh Dio, lasciarti" and "Qual nave smarrita").

Inside a temple, Tiridate is determined to marry Zenobia despite everything. Polissena brings him news that the army, led by Tigrane and Fraarte, has mutinied and the people have rebelled. Surrounded by his enemies, Tiridate now sees the error of his ways. He releases Zenobia and Radamisto, who celebrate their reunion ("Non ho più affanni"), asks forgiveness from his wife, and vows to rule for the benefit of his people for the rest of his life. All celebrate the fortunate turn of events.[7][8]

Context and analysis

The German-born Handel, after spending some of his early career composing operas and other pieces in Italy, settled in London, where in 1711 he had brought Italian opera for the first time with his opera Rinaldo. A tremendous success, Rinaldo created a craze in London for Italian opera seria, a form focused overwhelmingly on solo arias for the star virtuoso singers. In 1719, Handel was appointed music director of an organisation called the Royal Academy of Music (unconnected with the present day London conservatoire), a company under royal charter to produce Italian operas in London. Handel was not only to compose operas for the company but hire the star singers, supervise the orchestra and musicians, and adapt operas from Italy for London performance.[9][10]

Radamisto was Handel's first opera for the Royal Academy and was an enormous success with London audiences,as Handel's first biographer John Mainwaring noted;

'Many (ladies), who had forc'd their way into the house with an impetuosity ill suited to their rank and sex, actually fainted through the excessive heat and closeness of it. Several gentlemen were turned back, who had offered forty shillings for a seat in the gallery, after having despaired of getting any in the pit or boxes'.[7]

Lady Mary Cowper noted in her diary: "At night, Radamistus, a fine opera of Handel’s making. The King there with his ladies. The Prince in the stage-box. Great crowd."[11]

In the opinion of 18th century musicologist Charles Burney Radamisto was "more solid, ingenious, and full of fire than any drama which Handel had yet produced in this country."[12]

The opera is scored for strings, flute, two oboes, bassoon, two horns and continuo instruments (cello, lute, harpsichord).

Unusually for a Handel opera, the work contains a quartet, at the climax of the piece in Act Three. To Jonathan Keates, Radamisto is a work of the first stage of Handel's maturity as a composer, with its "masterly" invention and characterisation through music.[11]

Recordings

| Year | Cast: Radamisto, Zenobia, Polissena,Tigrane, Fraarte, Tiridate, Farasmane |

Conductor, orchestra |

Label |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | Ralf Popken, Juliana Gondek, Lisa Saffer, Dana Hanchard, Monika Frimmer, Michael Dean, Nicolas Cavallier |

Nicholas McGegan, Freiburger Barockorchester |

CD:Harmonia Mundi Cat:HMU 907111.13 |

| 2005 | Joyce DiDonato, Maite Beaumont, Patrizia Ciofi, Laura Cherici, Dominique Labelle, Zachary Stains, Carlo Lepore |

Alan Curtis, Il Complesso Barocco |

CD:Virgin Classics Cat:545 673–2[13] |

References

Notes

- Burrows, Donald. Handel (2nd ed.).

- "Handel:A Biographical Introduction". GF Handel.org. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- Opera/Chicago performance program

- Clements, Andrew (8 October 2010). "Radamisto". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 June 2014.

- "Man sieht nur mit den Ohren gut". Die Welt. 21 January 2013. Retrieved 20 June 2014.

- Hauff, Andreas. "Sorgsam abgezirkelt – Händels "Radamisto" historisierend inszeniert in Karlsruhe | nmz - neue musikzeitung". www.nmz.de. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- Best, Terence. "Synopsis of Radamisto". Handelhouse.org. Handel House Museum. Archived from the original on 6 February 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2014.

- "Synopsis of Radamisto". Naxos.com. Naxos. Retrieved 20 June 2014.

- Dean, W. & J.M. Knapp (1995) Handel's operas 1704–1726, p. 298.

- Strohm, Reinhard (20 June 1985). Essays on Handel and Italian opera by Reinhard Strohm. ISBN 9780521264280. Retrieved 2013-02-02 – via Google Books.

- Jonathan Keates: Handel: The Man and his Music. Fayard 1995, ISBN 2-213-59436-8.

- Charles Burney: A General History of Music: from the Earliest Ages to the Present Period. Vol. 4, London 1789,Cambridge University Press 2010, ISBN 978-1-1080-1642-1, p. 259.

- "Recordings of Radamisto". Operadis.com. Retrieved 20 June 2014.

Sources

- Burrows, Donald (2012). Handel (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199737369.

- Dean, Winton; Knapp, J. Merrill (1987). Handel's Operas, 1704–1726. Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-315219-3. The first of the two volume definitive reference on the operas of Handel

External links

- Italian libretto

- Score of Radamisto (ed. Friedrich Chrysander, Leipzig 1875)

- "Prompt Book for Radamisto". Theatre & Performance. Victoria and Albert Museum. Archived from the original on 2011-04-14. Retrieved 2011-03-24.