Rudaba

Rudābeh (Persian: رودابه [ruːdɒːˈbe]) is a Persian mythological female figure in Ferdowsi's epic Shahnameh. She is the princess of Kabul, daughter of Mehrab Kaboli and Sindukht, and later she becomes married to Zal, as they become lovers. They had two children, including Rostam, the main hero of the Shahnameh.[1]

Etymology

The word Rudābeh consists of two sections. "Rud" and "āb", "Rud" means child and "āb" means shining, therefore means shining child (according to Dehkhoda Dictionary).

Marriage to Zal

The Shahnama describes Rudaba with these words:

- About her silvern shoulders two musky black tresses curl, encircling them with their ends as though they were links in a chain.

- Her mouth resembles a pomegranate blossom, her lips are cherries and her silver bosom curves out into breasts like pomegranates.

- Her eyes are like the narcissus in the garden and her lashes draw their blackness from the raven's wing.

- Her eyebrows are modelled on the bows of Teraz powdered with fine bark and elegantly musk tinted.

- If you seek a brilliant moon, it is her face; if you long for the perfume of musk, it lingers in her tresses

- From top to toe she is Paradise gilded; all radiance, harmony and delectation.

- (Shahnama 1:21-3)

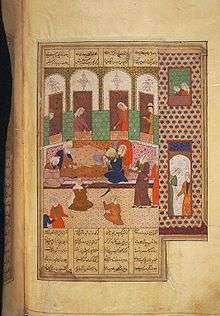

It was this description and Rudaba's physical beauty that initially attracted Zal. Rudaba also consulted her ladies-in-waiting about Zal. Zal came to the walls of Rudaba's palace where Rudaba let down her tresses to Zal as a rope and he immediately climbed from base to summit. Rudaba seated Zal on the roof and they both talked to each other for a long time. Although such actions were seen as unacceptable according to Islamic traditions, it was nevertheless the cultural norms of Iran that Ferdowsi wanted to highlight.

Zal, consulted his advisors over Rudaba. They at last advised him to write a full account of the circumstances to his father, Sam. Sam and the Mubeds, knowing that Rudaba's father, chief of Kabul, was Babylonian from the family of Zahhak, did not approve of the marriage. Zal reminded his father of the oath he had made to fulfill all his wishes.

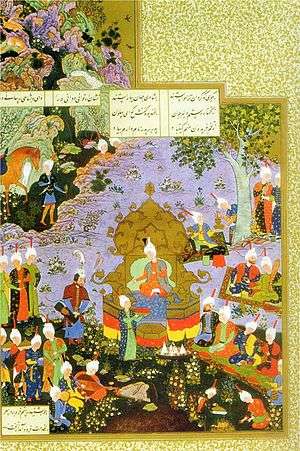

Finally, the ruler referred the question to astrologers, to discover whether the marriage between Zal and Rudaba would be prosperous or not and he was informed that a child of Zal and Rudabeh would be the conqueror of the world. When Zal arrived at the court of Manuchihr, he was received with honour, and having read the letter of Sam, the Shah approved of the marriage.

The marriage took place in Kabul, where Zal and Rudaba first met each other.

Motherhood

In Persian mythology, Rudabeh's labor of Rostam was prolonged due to the extraordinary size of her baby. Zal was certain that his wife would die in labor. Rudabeh was near death when at last Zal recollected the feather of the Simurgh, and followed the instructions which he had received, by placing it on the sacred fire. The Simurgh appeared and instructed him upon how to perform a caesarean section (rostamzad), thus saving Rudabeh and the child, who later on became one of the greatest Persian heroes.

Legacy

An English translation of the story exists in The story-book of the Shah; or, Legends of old Persia, in prose format.[2]

Scholarship points that the love story of Zal and princess Rudabah is related to an Afghan folktale tale named The Romance of Mongol Girl and Arab Boy.[3]

Notes

- Shahbazi, A. Shapur. "RUDĀBA". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- Sykes, Ella Constance. The story-book of the Shah; or, Legends of old Persia. London: J. Macqueen. 1901. pp. 73-94.

- Dorson, Richard M. Folktales told around the world. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press. 1978. pp. 209-210. ISBN 0-226-15874-8

Further reading

- Saadi-nejad, Manya. "Sūdābeh and Rūdābeh: Mythological Reflexes of Ancient Goddesses." Iran & the Caucasus 20, no. 2 (2016): 205-14. Accessed May 5, 2020. doi:10.2307/26548889.

External links

- A king's book of kings: the Shah-nameh of Shah Tahmasp, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Rudaba

.png)