Qusayr 'Amra

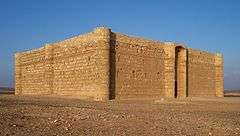

Qusayr 'Amra or Quseir Amra, lit. "small qasr of 'Amra", sometimes also named Qasr Amra (قصر عمرة / ALA-LC: Qaṣr ‘Amrah), is the best-known of the desert castles located in present-day eastern Jordan. It was built some time between 723 and 743, by Walid Ibn Yazid, the future Umayyad caliph Walid II,[1] whose dominance of the region was rising at the time. It is considered one of the most important examples of early Islamic art and architecture.

| Qusayr 'Amra, Qasr Amra | |

|---|---|

| Native name Arabic: قصر عمرة | |

East (front) elevation and portion of south profile, 2009 | |

| Location | Zarqa Governorate, Jordan |

| Coordinates | 31.801935°N 36.57663°E |

| Elevation | 520m |

| Built | 743 A.D. |

| Official name: Quseir Amra | |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, iii, iv |

| Designated | 1985 (9th session) |

| Reference no. | 327 |

| State Party | |

| Region | Arab States |

Location of Qusayr 'Amra, Qasr Amra in Jordan | |

The building is actually the remnant of a larger complex that included an actual castle, meant as a royal retreat, without any military function, of which only the foundation remains. What stands today is a small country cabin. It is most notable for the frescoes that remain mainly on the ceilings inside, which depict, among others, a group of rulers, hunting scenes, dancing scenes containing naked women, working craftsmen, the recently discovered "cycle of Jonah", and, above one bath chamber, the first known representation of heaven on a hemispherical surface, where the mirror-image of the constellations is accompanied by the figures of the zodiac. This has led to the designation of Qusayr 'Amra as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[2][3][4][1][5][6]

That status, and its location along Jordan's major east–west highway, relatively close to Amman, have made it a frequent tourist destination.

Location and access

Qasr Amra is on the north side of Jordan's Highway 40, roughly 85 kilometres (53 mi) from Amman and 21 kilometres (13 mi) southwest of Al-Azraq.[7]

It is currently within a large area fenced off in barbed wire. An unpaved parking lot is located at the southeast corner, just off the road. A small visitor's center collects admission fees. The castle is located in the west of the enclosed area, below a small rise.

Description

Traces of stone walls used to enclose the site suggest it was part of a 25-hectare (62-acre) complex; there are remains of a castle which could have temporarily housed a garrison of soldiers.[7]

Just to the southeast of the building is a well 40 metres (130 ft) deep, and traces of the animal-driven lifting mechanism and a dam have been found as well.[7]

The architecture of the reception-hall-cum-bathhouse is identical to that of Hammam al-Sarah, also in Jordan, except the latter was erected using finely-cut limestone ashlars (based on the Late Roman architectural tradition), while Amra's bath was erected using rough masonry held together by gypsum-lime mortar (based on the Sasanian architectural tradition).[8]

It is a low building made from limestone and basalt. The northern block, two stories high, features a triple-vaulted ceiling over the main entrance on the east facade. The western wings feature smaller vaults or domes.

Today, Qasr Amra is in a poorer condition than the other desert castles such as Qasr Kharana, with graffiti damaging some frescoes. However, conservation work is underway supported by World Monuments Fund, the Istituto Superiore per la Conservazione ed il Restauro, and Jordan's Department of Antiquities.[1]

History

Construction: who and when

One of the six kings depicted is King Roderick of Spain, whose short reign (710-712) was taken to indicate the date of the image, and possibly the building, to around 710. Therefore, for a long time researchers believed that sitting caliph Walid I was the builder and primary user of Qasr Amra, until doubts arose, making specialists believe that one of two princes who later became caliph themselves, Walid or Yazid, were the more likely candidates for that role.[9] The discovery of an inscription during work in 2012 has indeed allowed to date the structure to the two decades between 723 and 743, when it was commissioned by Walid Ibn Yazid,[1] crown prince under caliph Hisham and his successor for a short reign as caliph in 743-744.[6]

Both princes spent long periods of time away from Damascus, the Umayyad seat, before assuming the throne. Walid was known to indulge in the sort of sybaritic activities depicted on the frescoes, particularly sitting on the edge of pools listening to music or poetry. One time he was entertained by performers dressed as stars and constellations, suggesting a connection to the sky painting in the caldarium. Yazid's mother was a Persian princess, suggesting a familiarity with that culture, and he too was known for similar pleasure-seeking.[9]

Key considerations in placement of the desert castles centered on access and proximity to the ancient routes running north from Arabia to Syria. A major route ran from the Arabian city of Tayma via Wadi Sirhan toward the plain of Balqa in Jordan and accounts for the location of Qusayr Amra and other similar fortifications such as Qasr Al-Kharanah and Qasr al-tuba.[10]

Rediscovery in 1898

The abandoned structure was re-discovered by Alois Musil in 1898, with the frescoes made famous in drawings by the Austrian artist Alphons Leopold Mielich for Musil's book. In the late 1970s a Spanish team restored the frescoes. The castle was made a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1985 under criteria i), iii), and iv) ("masterpiece of human creative genius", "unique or at least exceptional testimony to a cultural tradition" and "an outstanding example of a type of building, architectural or technological ensemble or landscape which illustrates a significant stage in human history").

Frescoes

Qasr Amra is most notable for the frescoes on the inside walls._Walid_bin_Yazid.jpg)

Fresco of Caliph Al Walid II

Reception hall

The main entry vault has scenes of hunting, fruit and wine consumption, and naked women. Some of the animals shown are not abundant in the region but were more commonly found in Persia, suggesting some influence from that area. One surface depicts the construction of the building. Near the base of one wall a haloed king is shown on a throne. An adjoining section, now in Berlin's Pergamon Museum, shows attendants as well as a boat in waters abundant with fish and fowl.

Throne apse

An image known as the "six kings" depicts the Umayyad caliph and the rulers of realms near and far. Based on details and inscriptions in the image, four of the depicted kings are identified as the Byzantine Emperor, the Visigothic king Roderic, the Sassanid Persian Shah, and the Negus of Ethiopia.[11] The last one was for a long time unidentified, speculated to be the Turkish, Chinese, or Indian ruler,[9][11] and now known to represent the emperor of China.[1] Its intent was unclear. The Greek word ΝΙΚΗ nike, meaning victory, were discovered nearby, suggesting that the "six kings" image was meant to suggest the caliph's supremacy over his enemies.[9] Another possible interpretation is that the six figures are depicted in supplication, presumably towards the Caliph who would be seated in the hall.[11]

Bath

The frescoes in all rooms but the caldarium reflect the advice of contemporary Arab physicians. They believed that baths drained the spirits of the bathers, and that to revive "the three vital principles in the body, the animal, the spiritual and the natural," the bath's walls should be covered with pictures of activities like hunting, of lovers, and of gardens and palm trees.[9]

Apodyterium

The apodyterium, or changing room, is decorated with scenes of animals engaging in human activities, particularly performing music. One ambiguous image has an angel gazing down on a shrouded human form. It has often been thought to be a death scene, but some other interpretations have suggested the shroud covers a pair of lovers.[9] Three blackened faces on the ceiling have been thought to represent the stages of life. Christians in the area believe the middle figure is Jesus Christ.[9]

Tepidarium

On the walls and ceiling of the tepidarium, or warm bath, are scenes of plants and trees similar to those in the mosaic at the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus. They are interspersed with naked females in various poses, some bathing a child.[9]

Caldarium

The caldarium or hot bath's hemispheric dome has a representation of the heavens in which the zodiac is depicted, among 35 separate identifiable constellations. It is believed to be the earliest image of the night sky painted on anything other than a flat surface. The radii emerge not from the dome's center but, accurately, from the north celestial pole. The angle of the zodiac is depicted accurately as well. The only error discernible in the surviving artwork is the counterclockwise order of the stars, which suggests the image was copied from one on a flat surface.[9]

See also

References

- Qusayr 'Amra, World Monuments Fund, accessed 14 December 2019

- "The Frescoes of Qusayr Amra". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 14 December 2019.

- Raied T. Shuqum, Jordan's Qusayr Amra is a bathhouse for the noble, The Arab Weekly, 28/08/2015

- Fresco in Qasr Amra showing a hunter killing an animal and a dancing woman, Nicola & Pina Giordania, Frescoes in Qasr Amra, Jordan, UNESCO World Heritage Sites, 2005

- A. P., review of The Zodiac of Quṣayr 'Amra by Fritz Saxl; The Astronomical Significance of the Zodiac of the Quṣayr 'Amra by Arthur Beer, Isis, Vol. 19, No. 3 (Sep., 1933), pp. 504-506, The University of Chicago Press on behalf of The History of Science Society

- The Colors of the Prince: Conservation and Knowledge in Qusayr 'Amra, 12 November 2014, accessed 14 December 2019

- Khouri, Rami (September–October 1990). "Qasr'Amra". Saudi Aramco World. 41 (5). Archived from the original on 2010-01-03. Retrieved 2009-05-18.

- Arce, Ignacio (2008). Umayyad Building Techniques And The Merging Of Roman-Byzantine And Partho-Sassanian Traditions: Continuity And Change. p. 498.

- Baker, Patricia (July–August 1980). "The Frescoes of Amra". Saudi Aramco World. 31 (4): 22–25. Archived from the original on 2008-08-29. Retrieved 2009-05-28.

- Robinson, Chase (2011). The New Cambridge History of Islam. Cambridge University Press. p. 669. ISBN 9781139055932.

- Williams, Betsy. "Qusayr 'Amra". The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Bibliography

- Alois Musil: Ḳuṣejr ʿAmra, Kaiserliche Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien, Wien : k.k. Hof- u. Staatsdruckerei 1907, on-line

- Martin Almagro, Luis Caballero, Juan Zozaya y Antonio Almagro, Qusayr Amra : residencia y baños omeyas en el desierto de Jordania, Ed. Instituto Hispano-Arabe de Cultura, 1975

- Martín Almagro, Luis Caballero, Juan Zozaya y Antonio Almagro, Qusayr Amra : Residencia y Baños Omeyas en el desierto de Jordania, Ed. Fundación El Legado Andalusí, 2002

- Garth Fowden, Qusayr 'Amra : Art and the Umayyad Elite In Late Antique Syria, Ed. University of California Press, 2004

- Claude Vibert-Guigue et Ghazi Bisheh, Les peintures De Qusayr 'Amra, Ed. Institut français du Proche-Orient, 200

- Hana Taragan, "Constructing a Visual Rhetoric: Images of Craftsmen and Builders in the Umayyad Palace at Qusayr ‘Amra," Al-Masaq: Islam and the Medieval Mediterranean, 20,2 (2008), 141-160.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Quseir Amra. |