Qasr Al-Kharanah

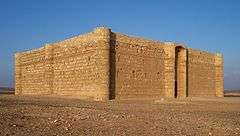

Qasr Kharana (Arabic: قصر خرّانة), sometimes Qasr al-Harrana, Qasr al-Kharanah, Kharaneh or Hraneh, is one of the best-known of the desert castles located in present-day eastern Jordan, about 60 kilometres (37 mi) east of Amman and relatively close to the border with Saudi Arabia. It is believed to have been built sometime before the early 8th century AD, based on a graffito in one of its upper rooms, despite visible Sassanid influences. A Greek or Byzantine house may have existed on the site. It is one of the earliest examples of Islamic architecture in the region.

| Qasr Kharana | |

|---|---|

قصر خرّانة | |

South and west elevations, 2009 | |

| |

| General information | |

| Type | Castle |

| Architectural style | Islamic |

| Location | Amman Governorate, Jordan |

| Coordinates | 31°43′44″N 36°27′46″E |

| Elevation | 659 metres (2,162 ft) |

| Completed | by 710 AD |

| Owner | Jordanian Ministry of Antiquities |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 2 |

| Floor area | 1,225 square metres (13,190 sq ft)[1] |

Its purpose remains unclear today. "Castle" is a misnomer as the building's internal arrangement does not suggest a military use, and slits in its wall could not have been designed for arrowslits. It could have been a caravanserai, or resting place for traders, but lacks the water source such buildings usually had close by and is not on any major trade routes.

It remains very well preserved, whatever its original use. Since it is located just off a major highway and is within a short drive of Amman, it has become one of the most visited of the desert castles. Archaeologist Stephen Urice wrote his doctoral dissertation, later published as a book, on Qasr Kharana, based on his work restoring the building in the late 1970s.

Building

The castle is just south of Highway 40, an important desert road that links Amman with Azraq, the Saudi Arabian border and remote areas of Eastern Jordan and Iraq. It sits on a slight rise just 15 metres (49 ft) above the surrounding desert. The only other structures in the area are power lines.

The area is fenced off with a visitors' center on the southeast corner, where the main entrance to the castle area is located. An unpaved driveway leads from the highway to a dirt parking lot large enough for cars and several buses located just south of the entrance.

The architectural style and the decoration of the building show influences from Syrian, Parthian, and Sasanian traditions. Some scholars argue that structure was built during the Sasanian occupation of the area in 620s.[2]

The building itself is a square 35 metres (115 ft) on each side, with small projecting corner towers and a projecting rounded entrance on the south side. It is made of rough limestone blocks set in a mud-based mortar. Decorative courses of flat stones run through the facing.[3]

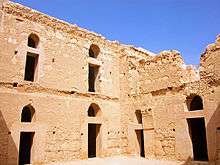

On the inside the building has 60 rooms on two levels arranged around a central courtyard, with a rainwater pool in the middle. Many of the rooms have small slits for light and ventilation. Some of the rooms are decorated with pilasters, medallions and blind niches finished in plaster.[3] A graffito in one of the upstairs rooms has allowed the building to be dated to c. 710.

Aesthetics

Qasr Kharana combines different regional traditions with the influence of the then-new religion of Islam to create a new style. Syrian building traditions influenced the design of the castle, with Sassanid building techniques applied.[4]

The layout follows Syrian houses, themselves influenced by Byzantine and Roman customs. Several rooms are arranged around a saloon, with the house and another apartment arranged around a central courtyard. Like Sassanid buildings, the castle's structural system is transverse arches supporting barrel vaults.[4]

The site made it necessary to modify those building techniques slightly. The arches are not connected to the carrying wall, instead placed on bearing arms. The overall weight of the structure keeps these elements together. Some newer building materials, such as wooden lintels, were used, allowing the building to be more flexible and resist earthquakes.[4]

Islamic concepts of public and private were satisfied through the narrow slits offering views to (and from) the outside, larger windows on the inside and the north terrace separating the two apartments. A room on the south side was set aside for prayer.[4]

The wall slits could not have been used by archers as they are the wrong height and shape. Instead they served to control dust and light and took advantage of air pressure differentials to cool the rooms, via the Venturi effect.[4]

History

The castle was built in the early Umayyad period by the Umayyad caliph Walid I whose dominance of the region was rising at the time. Qasr Kharana is an important example of early Islamic art and architecture.

Scholarship has suggested that Qasr Kharana might have served a variety of defensive, agricultural and/or commercial agendas similar to other Umayyad palaces in greater Syria. Having a limited water supply it is probable that Qasr Kharana sustained only temporary usage. There are different theories concerning the function of the castle: it may have been a fortress, a meeting place for Bedouins (between themselves or with the Umayyad governor), or used as a caravenserai. The latter is unlikely as it is not directly on a major trade route of the period and lacks the groundwater source that would have been necessary to sustain large herds of camel.

In later centuries the castle was abandoned and neglected. It suffered damage from several earthquakes. Alois Musil rediscovered it in 1901, and in the late 1970s it was restored. During the restoration some changes were made. A door in the east wall was closed, and some cement and plaster was used that was inconsistent with the existing material.[4] Stephen Urice wrote his doctoral dissertation on the castle, published as a book, Qasr Kharana in the Transjordan, in 1987 following the restoration.[5]

Qasr Kharana today

The castle is today under the jurisdiction of the Jordanian Ministry of Antiquities. The kingdom's Ministry of Tourism controls access to the site via the new visitor's center, charging an admission fee of JD 2 to the site during daylight hours. A Bedouin merchant is also allowed to sell handcrafts and drinks in the parking lot, as at many other Jordanian tourist sites.

Inside, a large interpretive plaque in Arabic and English is located just inside the main entrance. Visitors are free to explore the entire building, although some of the corridors overlooking the courtyard on the second story do not have guardrails and those who walk there must be careful.

See also

- Desert castles

References

- Ettinghausen, Richard; Grabar, Oleg; Jenkins, Marilyn (2001). Islamic Art and Architecture, 650–1250. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-300-08869-4. Retrieved May 12, 2009.

- Arce, Ignacio (1 January 2008). "Umayyad Building Techniques And The Merging Of Roman-Byzantine And Partho-Sassanian Traditions: Continuity And Change". Technology in Transition A.D. 300-650: 498–499. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- Petersen, Andrew (2002). Dictionary of Islamic Architecture. London: Routledge. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-203-20387-3. Retrieved May 13, 2009.

- Ilayan, J.S.A.; "The Development of Structural Concept and Architectural Form in Qasr Kharana" (PDF)., UNESCO.

- Urice, Stephen K. (1987), Qasr Kharana in the Transjordan, Durham, N.C.: American Schools of Oriental Research, ISBN 0-89757-207-6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Qasr_Kharana. |