Quokka

The quokka, also known as the short-tailed scrub wallaby (/ˈkwɒkə/) (Setonix brachyurus), the only member of the genus Setonix, is a small macropod about the size of a domestic cat.[4] Like other marsupials in the macropod family (such as kangaroos and wallabies), the quokka is herbivorous and mainly nocturnal.[5]

| Quokka | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Infraclass: | Marsupialia |

| Order: | Diprotodontia |

| Family: | Macropodidae |

| Subfamily: | Macropodinae |

| Genus: | Setonix Lesson, 1842[2] |

| Species: | S. brachyurus |

| Binomial name | |

| Setonix brachyurus | |

| |

| Geographic range | |

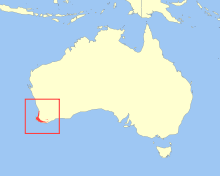

Quokkas are found on some smaller islands off the coast of Western Australia, particularly Rottnest Island, just off Perth, and also Bald Island near Albany, and in isolated, scattered populations in forest and coastal heath between Perth and Albany. A small colony exists at the eastern limit of their range in a protected area of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve, where they co-exist with the critically endangered Gilbert's potoroo.[6]

Description

A quokka weighs 2.5 to 5.0 kg (5.5 to 11.0 lb) and is 40 to 54 cm (16 to 21 in) long with a 25-to-30 cm-long (9.8-to-11.8 in) tail, which is quite short for a macropod. It has a stocky build, well developed hind legs, rounded ears, and a short, broad head. Its musculoskeletal system was originally adapted for terrestrial bipedal saltation, but over its evolution, its system has been built for arboreal locomotion.[7] Although looking rather like a very small kangaroo, it can climb small trees and shrubs up to 1.5 metres (4 ft 11 in).[8] Its coarse fur is a grizzled brown colour, fading to buff underneath. The quokka is known to live for an average of 10 years.[9]

Quokkas have a promiscuous mating system.[10] After a month of gestation, females give birth to a single baby called a joey. Females can give birth twice a year and produce about 17 joeys during their lifespan.[9] The joey lives in its mother's pouch for six months. Once it leaves the pouch, the joey relies on its mother for milk for two more months and is fully weaned around eight months after birth.[9] Females sexually mature after roughly 18 months.[11] When a female quokka with a joey in her pouch is pursued by a predator, she may drop her baby onto the ground; the joey produces noises, which may serve to attract the predator's attention, while the mother escapes.[12]

Discovery by Europeans

Dutch mariner Samuel Volckertzoon wrote of sighting "a wild cat" on Rottnest Island in 1658.[13] In 1696, Willem de Vlamingh mistook them for giant rats and named the island "Rotte nest", which comes from the Dutch word Rattenest, meaning "rat nest".[14]

The word "quokka" is derived from a Nyungar word, which was probably gwaga.[15]

Ecology

In the wild, its roaming is restricted to a very small range in the South West of Western Australia, with a number of small scattered populations. One large population exists on Rottnest Island and a smaller population is on Bald Island near Albany. The islands are free of certain predators such as red foxes and cats. On Rottnest, quokkas are common and occupy a variety of habitats, ranging from semiarid scrub to cultivated gardens.[16] Prickly Acanthocarpus plants, which are unaccommodating for humans and other relatively large animals to walk through, provide their favorite daytime shelter for sleeping.[17] Additionally, they are known for their ability to climb trees.[9]

Diet

Like most macropods, quokkas eat many types of vegetation, including grasses, sedges and leaves. A study found that Guichenotia ledifolia, a small shrub species of the family Malvaceae, is one of the quokka's favoured foods.[17] Rottnest Island visitors are urged to never feed quokkas, in part because eating "human food" can cause dehydration and malnourishment, both of which are detrimental to the quokka's health.[18] Despite the relative lack of fresh water on Rottnest Island, quokkas do have high water requirements, which they satisfy mostly through eating vegetation. On the mainland, quokkas only live in areas that have 600 mm (24 in) or more of rain per year.[19]

Population

At the time of colonial settlement, the quokka was widespread and abundant, with its distribution encompassing an area of about 41,200 km2 (15,900 sq mi) of the South West of Western Australia, including the two offshore islands, Bald and Rottnest. By 1992, following extensive population declines in the 20th century, the quokka's distribution on the mainland had been reduced by more than 50% to an area of about 17,800 km2 (6,900 sq mi).[20]

Despite being numerous on the small, offshore islands, the quokka is classified as vulnerable. On the mainland, where it is threatened by introduced predatory species such as red foxes, cats, and dogs, it requires dense ground cover for refuge. Clearfell logging, agricultural development, and housing expansion have reduced their habitat, contributing to the decline of the species, as has the clearing and burning of the remaining swamplands. Moreover, quokkas usually have a litter size of one and successfully rear one young each year. Although they are constantly mating, usually one day after the young are born, the small litter size, along with the restricted space and threatening predators, contributes to the scarcity of the species on the mainland.[21]

An estimated 4,000 quokkas live on the mainland, with nearly all mainland populations being groups of fewer than 50, although one declining group of over 700 occurs in the southern forest between Nannup and Denmark.[20][22] In 2015, an extensive bushfire near Northcliffe nearly eradicated one of the local mainland populations, with an estimated 90% of the 500 quokkas dying.[23]

In 2007, the quokka population on Rottnest Island was estimated at between 8,000 and 12,000. Snakes are the quokka's only predator on the island. The population on smaller Bald Island, where the quokka has no predators, is 600–1,000. At the end of summer and into autumn, a seasonal decline of quokkas occurs on Rottnest Island, where loss of vegetation and reduction of available surface water can lead to starvation.[20][24]

Human interaction

Quokkas have little fear of humans and commonly approach people closely, particularly on Rottnest Island, where a prevalent population exists. Though quokkas have a reputation of being the happiest animal on Earth, annually, a few dozen cases of quokkas biting people, especially children, are reported.[25] There are certain restrictions regarding feeding. It is illegal for members of the public to handle the animals in any way, and feeding, particularly of "human food", is especially discouraged, as they can easily get sick. An infringement notice carrying a A$300 fine can be issued by the Rottnest Island Authority for such an offense.[26] The maximum penalty for animal cruelty is a A$50,000 fine and a five-year prison sentence.[27][28][29]

Quokkas can also be observed at several zoos and wildlife parks around Australia, including the Perth Zoo,[30] the Taronga Zoo,[31] Wild Life Sydney,[32] and the Adelaide Zoo.[33] Physical interaction is generally not permitted without explicit permission from supervising staff.

Quokka behavior in response to human interaction has been examined in zoo environments. One brief study indicated fewer animals remained visible from the visitor paths when the enclosure was an open or walk-through environment. This may have been due to the quokkas acquiring avoidance behavior of visitors, which the authors propose has implications for stress management in their exhibition to the public.[34]

Quokka selfies

In the mid-2010s, quokkas earned a reputation on the internet as "the world's happiest animals" and symbols of positivity due to their beaming smiles.[35] Many photos of smiling quokkas have since gone viral,[36] and the "quokka selfie" has become a popular social media trend, with celebrities such as Chris Hemsworth, Shawn Mendes, Margot Robbie and Roger Federer participating.[37] Tourist numbers to Rottnest Island have subsequently increased.[36]

Noting the popularity of smiling quokkas, the fact-checking website Snopes confirmed in 2020 that the animal exists, saying it had received questions from readers who thought it "was simply too cute to be real".[38]

See also

References

- de Tores, P.; Burbidge, A.; Morris, K. & Friend, T. (2008). "Setonix brachyurus". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. 2008: e.T20165A9156418. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T20165A9156418.en.

- Lesson, R.-P. (1842). "Groupe: Setonix". Nouveau Tableau du Règne Animal: Mammifères. Paris: Arthus Bertrand. p. 194.

- Quoy, [Jean René Constant]; Gaimard, [Joseph Paul] (1830). "Kangurus brachyurus". Voyage de découvertes de l'Astrolabe: Zoologie. 1. Paris: J. Tastu. pp. 114–116.

- Groves, C. P. (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 69. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- "Rottnest Island Wildlife".

- Sinclair, Elizabeth. "Australian endangered species: Gilbert's Potoroo". The Conversation. Retrieved 2017-10-20.

- Warburton, Natalie M.; Yakovleff, Maud; Malric, Auréline (2012). "Anatomical adaptations of the hind limb musculature of tree-kangaroos for arboreal locomotion (Marsupialia : Macropodinae)". Australian Journal of Zoology. 60 (4): 246–158. doi:10.1071/ZO12059.

- "Quokka videos, photos and facts - Setonix brachyurus". Arkive. Archived from the original on 2018-03-20. Retrieved 2018-03-19.

- Burrell, Sue (October 30, 2015). "Animal Species: Quokka". Retrieved March 18, 2018.

- McLean, Ian G.; Schmitt, Natalie T. (1999). "Copulation and associated behavior in the quokka, Setonix brachyurus". Australian Mammalogy. 21: 139–142.

- "Quokka Facts | Quokkas | Australian Marsupials". Animalfactguide.com. Retrieved 2016-08-25.

- Hayward, Matt W.; de Tores, Paul J.; Augee, Michael L.; Banks, Peter B. (2005). "Mortality and survivorship of the quokka (Setonix brachyurus)(Macropodidae: Marsupialia) in the northern jarrah forest of Western Australia" (PDF). Wildlife Research. 32 (8): 715–722. doi:10.1071/WR04111. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 March 2019.

- Flannery, Tim (2008). Chasing Kangaroos: A Continent, a Scientist, and a Search for the World's Most Extraordinary Creature. p. 30. ISBN 9781555848217.

- "Quokka". Australian Museum. Retrieved 2016-08-25.

- Dixon, R. M. W.; Moore, Bruce; Ramson, W. S.; Thomas, Mandy (2006). Australian Aboriginal Words in English: Their Origin and Meaning (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-554073-5.

- "A close encounter of the furry kind". Australian Geographic. 2010. Archived from the original on 2013-09-21. Retrieved 2010-04-22.

- Poole, H. L.; Mukaromah, L.; Kobryn, H. T.; Fleming, P. A. (2015). "Spatial analysis of limiting resources on an island: diet and shelter use reveal sites of conservation importance for the Rottnest Island quokka". Wildlife Research. 41 (6): 510–521. doi:10.1071/WR14083.

- "Quokkas and Wildlife". Rottnest Island. Retrieved 2016-08-25.

- Jones, Ann (17 October 2016). "Quokka smiles mask pain on Rottnest Island". Off Track. Radio National. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- de Tores, Paul; Williams, Richard; Podesta, Mia; Pryde, Jill (January 2013). "Quokka (Setonix brachyurus) Recovery Plan" (PDF). Bentley, WA: Department of Environment and Conservation, Government of Western Australia. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- Nocon, Wojtek. "Sentonix Brachyurus". Quokka. University of Michigan. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- Bain, Karlene (June 2015). "The ecology of the quokka (Setonix brachyurus)in the southern forests of Western Australia" (PDF). University of Western Australia. Crawley, WA: School of Animal Biology. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- Mainland quokka population decimated after 2015 bushfire near Northcliffe - ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation). Abc.net.au. Retrieved on 2016-12-24.

- "Setonix brachyurus — Quokka Glossary". Species Profile and Threats Database. Canberra: Department of the Environment. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- "Quokka". rove.me. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- Rottnest Island Regulations 1988 (WA), rr 40 & 73; sched. 4

- "Quokka cruelty: French tourists fined after pleading guilty to burning animal on Rottnest Island - ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation)". Abc.net.au. 2015-04-17. Retrieved 2016-08-25.

- Rottnest Island Regulations 2007 (WA), r 40

- Squires, Nick (12 January 2003). "Rare marsupials kicked to death in 'quokka soccer'". The Daily Telegraph (London).

- "Quokka - Perth Zoo". perthzoo.wa.gov.au.

- "Quokka". taronga.org.au. 10 July 2010. Archived from the original on 26 April 2018. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- "Our Quokkas Have Arrived (1)". www.wildlifesydney.com.au.

- "Quokka Fact Sheet - Adelaide Zoo". adelaidezoo.com.au.

- Hemsworth, Paul H.; Sherwen, Sally; Learmonth, Mark James (2018-07-01). "The effects of zoo visitors on Quokka (Setonix brachyurus) avoidance behavior in a walk‐through exhibit". Zoo Biology. 37 (4): 223–228. doi:10.1002/zoo.21433. ISSN 1098-2361. PMID 29992613.

- "Wildlife photographer Suzana Paravac’s photo of a quokka nibbling leaf into heart captivates Instagrammers" (3 November 2019), The West Australian. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- Jones, Ann (17 October 2016). "Quokka smiles mask pain on Rottnest Island", ABC. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- Rintoul, Caitlyn (20 October 2019). "Shawn Mendes becomes latest celeb to rack up Instagram likes with quokka selfie at Rottnest", The West Australian. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- Evon, Dan (6 March 2020). "Is the Quokka a Real Animal?", Snopes. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

Further reading

- Ronald M. Nowak (1999), Walker's Mammals of the World (6th ed.), Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0-8018-5789-9, LCCN 98023686

External links