Qixi Festival

The Qixi Festival, also known as the Qiqiao Festival, is a Chinese festival celebrating the annual meeting of the cowherd and weaver girl in mythology.[2][3][4][5] It falls on the 7th day of the 7th lunar month on the Chinese calendar.[2][3][4][5]

| Qixi Festival | |

|---|---|

| Also called | Qiqiao Festival |

| Observed by | Chinese |

| Date | 7th day of 7th month on the Chinese lunar calendar |

| 2019 date | 7 August[1] |

| 2020 date | 25 August[1] |

| Related to | Tanabata (Japan), Chilseok (Korea) |

| Qixi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 七夕[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Evening of Sevens" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Qiqiao | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 乞巧[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Beseeching Skills" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The festival originated from the romantic legend of two lovers, Zhinü and Niulang,[3][5] who were the weaver girl and the cowherd, respectively. The tale of The Cowherd and the Weaver Girl has been celebrated in the Qixi Festival since the Han dynasty.[6] The earliest-known reference to this famous myth dates back to over 2600 years ago, which was told in a poem from the Classic of Poetry.[7] The Qixi festival inspired the Tanabata festival in Japan, Chilseok festival in Korea, and Thất Tịch festival in Vietnam.

The festival has variously been called the Double Seventh Festival,[5] the Chinese Valentine's Day,[8] the Night of Sevens,[3][9] or the Magpie Festival.

Mythology

The general tale is a love story between Zhinü (the weaver girl, symbolizing Vega) and Niulang (the cowherd, symbolizing Altair).[3] Their love was not allowed, thus they were banished to opposite sides of the Silver River (symbolizing the Milky Way).[3][10] Once a year, on the 7th day of the 7th lunar month, a flock of magpies would form a bridge to reunite the lovers for one day.[3] There are many variations of the story.[3]

Traditions

During the Han dynasty, the practices were conducted in accordance to formal ceremonial state rituals.[2] Over time, the festival activities also included customs that the common people partook.[2]

Girls take part in worshiping the celestials (拜仙) during rituals.[4] They go to the local temple to pray to Zhinü for wisdom.[5] Paper items are usually burned as offerings.[11] Girls may recite traditional prayers for dexterity in needlework,[5][12] which symbolize the traditional talents of a good spouse.[5] Divination could take place to determine possible dexterity in needlework.[11] They make wishes for marrying someone who would be a good and loving husband.[3] During the festival, girls make a display of their domestic skills.[3] Traditionally, there would be contests amongst those who attempted to be the best in threading needles under low-light conditions like the glow of an ember or a half moon.[11] Today, girls sometimes gather toiletries in honor of the seven maidens.[11]

The festival also held an importance for newlywed couples.[4] Traditionally, they would worship the celestial couple for the last time and bid farewell to them (辭仙).[4] The celebration stood symbol for a happy marriage and showed that the married woman was treasured by her new family.[4]

On this day, the Chinese gaze to the sky to look for Vega and Altair shining in the Milky Way, while a third star forms a symbolic bridge between the two stars.[6] It was said that if it rains on this day that it was caused by a river sweeping away the magpie bridge or that the rain is the tears of the separated couple.[13] Based on the legend of a flock of magpies forming a bridge to reunite the couple, a pair of magpies came to symbolize conjugal happiness and faithfulness.[14]

In some places people gather together and build a four meter long bridge(花桥) with big incensticks and decorate with colorful flowers. They burn the bridge at night and wish to bring happiness in life.

Literature

Due to the romance, elegancy as well as the beautiful symbolic meaning of the festival, there has been a lot of literature pieces, such as poems, popular songs and operas, since the Zhou Dynasty from 11th century B.C., which described the atmosphere of the festival or narrated the stories happened on that day, leaving us valuable literary treasure to understand better how the ancient Chinese spent their time on the festival and what exactly was their opinion towards it.

迢迢牽牛星-佚名(東漢) Far, Far Away, the Cowherd-Anonymous(Han Dynasty)

迢迢牽牛星, Far, far away, the Cowherd,

皎皎河漢女。 Fair, fair, the Weaving Maid,

纖纖擢素手, Nimbly move her slender white finger,

札札弄機杼。 Click-clack goes her weaving-loom.

終日不成章, All day she weaves, yet her web is still not done.

泣涕零如雨。 And her tears fall like rain.

河漢清且淺, Clear and shallow the Milky Way,

相去復幾許? They are not far apart!

盈盈一水間, But the stream brims always between.

脈脈不得語。 And, gazing at each other,they cannot speak.

(翻譯:楊憲益,戴乃迭) (Translated by Yang Xianyi, Dai Naidie)

秋夕-杜牧(唐朝) An Autumn Night -Du Mu (Tang Dynasty)

銀燭秋光冷畫屏, A candle flame flickers against a dull painted screen on an cool autumn night,

輕羅小扇撲流螢。 She holds a small silk fan to flap away dashing fireflies.

天階夜色涼如水, Above her hang celestial bodies as frigid as deep water,

坐看牽牛織女星。 She sat there watching Altair of Aquila and Vega of Lyra pining for each other in the sky.

(翻譯:曾培慈[15]) (Translated by Betty Tseng)

鶴橋仙-秦觀(宋朝) Immortals at the Magpie Bridge-Qin Guan (Song Dynasty)

纖雲弄巧, Clouds float like works of art,

飛星傳恨, Stars shoot with grief at heart.

銀漢迢迢暗渡。 Across the Milky Way the Cowherd meets the Maid.

金風玉露一相逢, When Autumn’s Golden Wind embraces Dew of Jade,

便勝却人間無數。 All the love scenes on earth, however many, fade.

柔情似水, Their tender love flows like a stream;

佳期如夢, Their happy date seems but a dream.

忍顧鶴橋歸路。 How can they bear a separate homeward way?

兩情若是久長時, If love between both sides can last for aye,

又豈在朝朝暮暮。 Why need they stay together night and day?

(翻譯:許淵沖) (Translated by Xu Yuanchong)

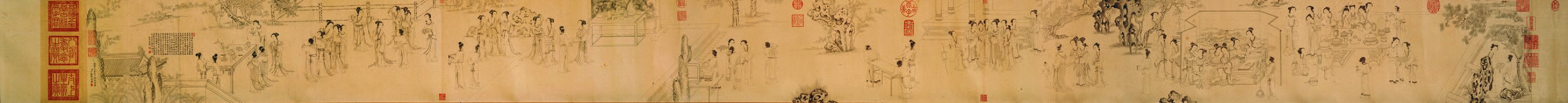

Gallery

Other

Interactive Google doodles have been launched since the 2009 Qixi Festival to mark the occasion.[16] The latest was launched for the 2019 Qixi Festival.[17]

See also

- Qixi Tribute

- Seven Sisters' Fruit

References

- Zhao 2015, 13.

- Brown & Brown 2006, 72.

- Poon 2011, 100.

- Melton & Baumann 2010, 912–913.

- Schomp 2009, 70.

- Schomp 2009, 89.

- Welch 2008, 228.

- Chester Beatty Library, online Archived 2014-10-22 at the Wayback Machine.

- Lai 1999, 191.

- Stepanchuk & Wong 1991, 83

- Kiang 1999, 132.

- Stepanchuk & Wong 1991, 82

- Welch 2008, 77.

- "English Translation of Chinese Poetry —— 中文詩詞英譯". English Translation of Chinese Poetry —— 中文詩詞英譯. Retrieved 2020-02-13.

- "QiXi Festival 2009". Archived from the original on 2019-06-13. Retrieved 2019-08-05 – via www.google.com.

- "Qixi Festival 2019". www.google.com.

Bibliography

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Qixi Festival. |

Hard copy

- Brown, Ju; Brown, John (2006). China, Japan, Korea: Culture and customs. North Charleston: BookSurge. ISBN 1-4196-4893-4.

- Kiang, Heng Chye (1999). Cities of aristocrats and bureaucrats: The development of medieval Chinese cityscapes. Singapore: Singapore University Press. ISBN 9971-69-223-6.

- Lai, Sufen Sophia (1999). "Father in Heaven, Mother in Hell: Gender politics in the creation and transformation of Mulian's mother". Presence and presentation: Women in the Chinese literati tradition. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-21054-X.

- Melton, J. Gordon; Baumann, Martin (2010). "The Double Seventh Festival". Religions of the world: A comprehensive encyclopedia of beliefs and practices (2nd ed.). Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-203-6.

- Poon, Shuk-wah (2011). Negotiating religion in modern China: State and common people in Guangzhou, 1900–1937. Hong Kong: Chinese University of Hong Kong. ISBN 978-962-996-421-4.

- Schomp, Virginia (2009). The ancient Chinese. New York: Marshall Cavendish Benchmark. ISBN 978-0-7614-4216-5.

- Stepanchuk, Carol; Wong, Charles (1991). Mooncakes and hungry ghosts: Festivals of China. San Francisco: China Books & Periodicals. ISBN 0-8351-2481-9.

- Welch, Patricia Bjaaland (2008). Chinese art: A guide to motifs and visual imagery. North Clarendon: Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8048-3864-1.

- Zhao, Rongguang (2015). A History of Food Culture in China. SCPG Publishing Corporation. ISBN 978-1-938368-16-5.

Online

- Ladies on the ‘Night of Sevens’ Pleading for Skills. Dublin: Chester Beatty Library.