Qasr Burqu'

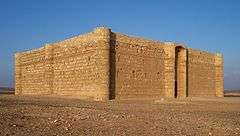

Qasr Burqu' is a set of ruins and an archaeological site in the badia of eastern Jordan and is the site of one of the earliest of the Umayyad desert castles.

Background

Under the Umayyad Caliphate, nobles and wealthy families belonging to the Umayyad dynasty erected small castles in semi-arid regions to serve as their country estates or hunting lodges. For the Ummayad aristocracy, hunting was a favoured pastime and these desert castles became important places of relaxation and entertainment.[1] In Arabic, these desert castles are known as qusur (sing: qasr). They were often built close to a water source or adjacent such as a natural oasis, and frequently sited along important trading routes, such as the ancient trade routes connecting Damascus with Medina and Kufa.[2]

The construction of a qasr typically followed a standard template; the main castle was a rectangular stone structure with an elaborate entrance and other buildings in the complex would include a hammam (bath house), a mosque, walled enclosures for animals and in some cases, dedicated buildings for processing produce such as olive oil. The complex also included a water reservoir or dam. [3] The interior rooms of the main castle were ornately decorated with floor-mosaics, frescoes or wall paintings featuring designs that exhibit both eastern and western influences. Most of the desert palaces were abandoned after the Umayyads fell from power in 750, leaving many projects incompleted and others were left to erode.[4]

The ruins of these desert castles can be found across the Middle East. While the majority of qusur are situated in modern-day Jordan, several are located in Syria, the West Bank and Israel, either in cities (Jerusalem and Ramla), in relatively green areas (al-Sinnabra, Khirbat al-Minya), or indeed in the desert (Qasr al-Hayr al-Gharbi and Qasr al-Hayr al-Sharqi, Jabal Says, Hisham's Palace). [5]

History

The region where Qasr Burqu' is located has been occupied since the Neolithic period.[6] Archaeological excavations reveal that a Roman fort was established on the site and a monastery was built there during the Byzantine period.[7] It became an Umayyad castle complex in around 700 CE when al-Walid I, who was still emir, rather than Caliph, either built it, or repaired existing structures to form a new palace complex.[8]

Qasr Burqu' is one of the earliest of the Umayyad desert castles in Jordan, and is also situated in one of the most remote regions.[9] It sits on the edge of an oasis formed on the edge of a basalt region in eastern Jordan.[10]

Description

Qasr Burqu' in the far northeast of Jordan is one of a number of Umayyad desert castles in the semi-arid region. It is situated about 100 km east of ad-Diyatheh and 70 km south-east of al-Namara, in the black basalt desert, and about 2 km from the Wadi Minqat, which holds water from the winter rains.[11] The site was important due to its natural shallow basin which collected rain waters in ponds.[12] Various water-catchment systems, of uncertain origin and unknown date, have been added to the site over time, in order to sustain larger populations that may have lived in the area at different times.[13] Carved rock inscriptions show that Bedouin tribes used the site as a seasonal encampment each spring throughout the Medieval period.[14]

The site's most significant surviving structure is a 5 metre tower, probably of Roman origin, and originally estimated to have been 13 metres in height.[15] The early Islamic palace complex was constructed around the Roman tower.[16] The enclosures are constructed of basalt, and were used to pen animals by nomadic peoples attracted to location to water their herds.[17]

It is one of the lesser desert castles in Jordan.[18] Although it is often described as one of the Umayyad desert castles, Svend Helms notes "it is neither a castle, nor is it in the desert" and most of the structures predate the Umayyad Caliphate.[19]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Qasr Burqu. |

References

- Petersen, A, Dictionary of Islamic Architecture, Routledge, 2002, p. 239; Meyers, E.M. (ed.), The Oxford Encyclopedia of Archaeology in the Near East, Volume 5, Oxford University Press, 1997, p. 241

- Khouri, R.G., The Desert Castles: A Brief Guide to the Antiquities, Al Kutba, 1988. pp 4-5

- Ettinghausen, R., Grabar, O. and Jenkins, M., Islamic Art and Architecture p 650

- Petersen, A., Dictionary of Islamic Architecture, Routledge, 2002, p. 296 ISBN 978-0-203-20387-3

- Teller, M., Jordan,Rough Guides, 2002 p. 200

- Betts, A.V. G. (ed), The Harra and the Hamad: Excavations and Explorations in Eastern Jordan, Sheffield Academic Press, Sheffield, UK, Chapter 1

- Barker, G. and Gilbertson, D., The Archaeology of Drylands: Living at the Margin, Routledge, 2003, pp 94-96; Bowersock, G.W., Roman Arabia, Harvard University Press, 1994, p. 99

- Fowden, G., Qusayr 'Amra: Art and the Umayyad Elite in Late Antique Syria, University of California Press, 2004 p. 289

- Helms, S., "A New Architectural Survey of Qaṣr Burquʽ, Eastern Jordan", Vol. 71, September 1991 , pp 191-215; Helmes, S., "A New Architectural Survey of Qasr Burqu', Eastern Jordan, The Antiquaries Journal, Volume 71, [Oxford University Press], 1991, pp 191-193

- Helmes, S., "A New Architectural Survey of Qasr Burqu', Eastern Jordan, The Antiquaries Journal, Volume 71, [Oxford University Press], 1991, pp 191-193

- Cameron, A. and King, G. R.D., "Land Use and Settlement Patterns." in Papers of the Second Workshop on Late Antiquity and Early Islam, Darwin Press, 1994, p. 54

- Kennedy, D. and Riley, D., Rome's Desert Frontiers, Routledge, 2012, p. 71

- Barker, G. and Gilbertson, D., The Archaeology of Drylands: Living at the Margin, Routledge, 2003, pp. 97-99; Kennedy, D. and Riley, D., Rome's Desert Frontiers, Routledge, 2012, p. 71

- Winnett, F.V. and Harding, G.L., Inscriptions from Fifty Safaitic Cairns, University of Toronto Press, 1978, p. 25; Jamme, A., "Inscriptions from Fifty Safaitic Cairns," in Niditch, S., Incantation Texts and Formulalc Language: A New Etymology for hwmry, p. 478

- Barker, G. and Gilbertson, D., The Archaeology of Drylands: Living at the Margin, Routledge, 2003, p. 96

- Kennedy, D. and Riley, D., Rome's Desert Frontiers, Routledge, 2012, p. 71

- Kennedy, D. and Riley, D., Rome's Desert Frontiers, Routledge, 2012, p. 72

- Kennedy, D. and Riley, D., Rome's Desert Frontiers, Routledge, 2012, pp 8-9

- Helms, Svend (1991). "A New Architectural Survey of Qaṣr Burquʽ, Eastern Jordan". The Antiquaries Journal. 71: 191–215. doi:10.1017/S000358150008687X. ISSN 1758-5309.