Qalqilya

Qalqilya or Qalqiliya (Arabic: قلقيلية, romanized: Qalqīlyaḧ); is a Palestinian city in the West Bank. Qalqilya serves as the administrative center of the Qalqilya Governorate. In the official 2007 census the city had a population of 41,739.[1] Qalqilya is surrounded by the Israeli West Bank barrier with a narrow gap in the east controlled by the Israeli military and a tunnel to Hableh.[3][4] The city is known for growing many oranges.

Qalqilya | |

|---|---|

| Other transcription(s) | |

| • Arabic | قلقيلية |

View of Qalqilya | |

Municipal Seal of Qalqilya | |

| Coordinates: 32°11′25″N 34°58′07″E | |

| Palestine grid | 146/177 |

| State | |

| Governorate | Qalqilya |

| Government | |

| • Type | City |

| • Head of Municipality | Othman Dawoud |

| Area | |

| • Jurisdiction | 25,637 dunams (25.6 km2 or 9.9 sq mi) |

| Population (2017)[1] | |

| • Jurisdiction | 51,683 |

| Name meaning | "a type of pomegranate", or "gurgling of water"[2] |

| Website | www.qalqiliamun.ps |

Etymology

Qalqilya was known as Calecailes in the Roman period, and Calcelie in the Frankish sources from the early Medieval times.[5] The word "Qalqilya" might be derived from a Canaanite term which means "rounded stones or hills".[6]

According to E.H. Palmer, the name came from "a type of pomegranate", or "gurgling of water".[2]

History

The vicinity of Qalqilya has been populated since prehistoric times, as attested to by the discovery of prehistoric flint tools.[7]

Ottoman era

In 1596, Qalqilya appeared in Ottoman tax registers (transliterated as Qalqili) as a village in the nahiya (subdistrict) of Bani Sa'b in the Liwa of Nablus. It had a population of 13 Muslim households and paid taxes on wheat, barley, summer crops, olives, and goats or beehives; a total of 3,910 akçe.[8]

In 1838, Robinson noted Kulakilieh as a village in Beni Sa'ab district, west of Nablus.[9]

In 1870, Victor Guérin found it to be a village with 200 inhabitants.[10]

In 1882, Qalqilya was described as "A large somewhat straggling village, with cisterns to the north and a pool on the south-west. The houses are badly built."[11] In 1883 some moved to there from nearby Baqat al-Hatab, and in 1909 a municipal council to administer Qalqilya was established.[12]

British Mandate era

In the 1922 census of Palestine conducted by the British Mandate authorities, Qalqilya had a population of 2,803 (2,794 Muslims and 9 Christians),[13] increasing in the 1931 census to 3,867 (3,855 Muslims and 12 Christians), in a total of 796 houses.[14]

In the 1945 statistics the population of Qalqilya was 5,850; 5,840 Muslims and 10 Christians,[15] who owned 27,915 dunams of land according to an official land and population survey.[16] Of this, 3701 dunams were for citrus and bananas, 3,232 were plantations and irrigable land, 16,197 used for cereals,[17] while 273 dunams were built-up (urban) land.[18]

1948 War

In the wake of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, and after the 1949 Armistice Agreements, Qalqilya came under Jordanian rule. During the war, many inhabitants from nearby villages, including Kafr Saba, Abu Kishk, Miska, Biyar 'Adas and Shaykh Muwannis fled to Qalqilya as refugees.[19]

Following the battle of the nearby Arab village of Kafr Saba, the residents of Qalqilya fled and later returned with the arrival of the Jordanian Arab Legion and the Iraqi expeditionary force, although the return was partial, as some 2,000 residents did not return. Those were upper class residents who moved to Nablus. The main reason for the partial return was the difficult economic situation in the front-line town and the inability to access the crop fields.[20]

Jordanian era

The area was annexed by Jordan in 1950. On the night of 10 October 1956 the Israeli army launched a raid against Qalqilya police station in response to a Jordanian attack on Israeli bus,[21] amongst other incidents.[22] The attack was ordered by Moshe Dayan and involved several thousand soldiers. During the fighting a paratroop company was surrounded by Jordanian troops and the survivors only escaped under close air-cover from four Israeli Air Force aircraft. Eighteen Israelis and between 70 and 90 Jordanians were killed in the operation.[23]

In 1961, the population of Qalqilya was 11,401.[24]

Post 1967

Since the Six-Day War in 1967, Qalqilya has been under Israeli occupation. Later that year, dozens of its inhabitants were evicted by Israel to Jordan, and at least 850 buildings were razed.[25] In his memoirs, Moshe Dayan described the destruction as a "punishment" that was designed to chase the inhabitants away contrary to the government policy.[26] The villagers were eventually allowed to return and the reconstruction of damaged houses was financed by the military authorities.[27] In September 1967, a census found 8,922 persons, of whom 1,837 were originally from Israeli territory.[28]

As part of the 1993 Oslo Accords between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), control of Qalqilya was transferred to the Palestinian National Authority (PNA) on 17 December 1995.[29]

In 2003, the Israeli West Bank barrier was built, encircling the town and separating it from agricultural lands on the other side of the wall.[30]

In November 2015, Israel arrested what it alleged to be a network of 24 Hamas militants active in the city.[31]

On October 20, 2017, the Palestinian city of Qalqilya named a street after Saddam Hussein and erected a memorial with his likeness, according to an Israeli newspaper. The monument was unveiled at a ceremony attended by the Qalqilya District Governor Rafi Rawajba and two other Palestinian officials. It bears the slogan “Saddam Hussein – The Master of the Martyrs in Our Age,” as well as “Arab Palestine from the River to the Sea,” a slogan often used by Hussein that refers to the Palestinian liberation movement.[32]

Geography

Qalqilya is located in the northwestern West Bank, straddling the border with Israel. It is 16 kilometers southwest of the Palestinian city of Tulkarm, and the nearest localities are the Arab-Israeli city of Tira and the Palestinian hamlet of 'Arab al-Ramadin al-Shamali to the northeast, the Palestinian village of Nabi Ilyas to the east, the Palestinian hamlets 'Arab Abu Farda and 'Arab ar-Ramadin al-Janubi and the Israeli settlement of Alfei Menashe to the southwest, and the Palestinian village Habla and Arab-Israeli town of Jaljuliya to the south.[12]

Qalqilya has an average elevation of 57 meters above sea level. The average annual rainfall 587.4 millimeters and the average annual temperature is 19 degrees Celsius.[12]

Demographics

The 1997 census by the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) recorded Qalqilya's population to be 22,168. The majority of the inhabitants (69.8%) were Palestinian refugees or their descendants.[33] In the 2007 census, Qalqilya's population grew to 41,739 (50.9% male and (49.1% female).[1] The number of registered households was 7,866. Among the largest families in Qalqilya are the Nazzal, Shreim, Dawood, Zeid, Sabawi and Al Qar'an.[12] In the 2017 census, Qalqiliya's population grew to 51,683.[34]

Government

Hamas won the 2006 municipal elections in Qalqiliya and one of its members, Wajih Qawas, became mayor, although he was incarcerated by Israel for much of his term. On 12 September 2009, the PNA dismissed Qawas for allowing Qalqiliya's debt to grow unchecked, failing to attract international funding for city projects and ignoring orders by the Palestinian government. Qawas, however, viewed his dismissal as a result of the ongoing feud between Hamas, which dominates the PNA in the Gaza Strip and Fatah, which dominates the PNA in the West Bank.[35] Human rights groups criticized Qawas's dismissal, condemning the intervention by the central Palestinian authorities in the affairs of an elected official.[35] During the 2012 municipal elections, Fatah member Othman Dawood was elected mayor.[36]

Economy

Between 1967 and 1995 almost 80 percent of Qalqilya's labor force worked for Israeli companies or industries in the construction and agriculture sectors. The remaining 20% engaged in trade and commerce, marketing across the Green Line. According to a field survey taken by the Applied Research Institute-Jerusalem (ARIJ), 45% of Qalqilya's working population was employed by government, 25% worked in agriculture, 15% worked in trade and commerce, 10% worked in industry and 5% worked in Israeli labor. In 2012, the unemployment rate was 22%, with those most affected formerly employed in agriculture, trade and services. The city is particularly known for its citrus crop and 17.6% of its lands are planted with citrus trees. Other major crops are olives and vegetables.[12]

As of 2012, there were 145 grocery stores, 35 produce stores, 18 bakeries, 18 butcheries, 133 service-oriented businesses, 80 various professional workshops, six hardware stores and ten stonemasons operating in Qalqilya.[12] Qalqilya Zoo, established in 1986, is the largest zoo in the West Bank and according to its owner, is the city's single-largest employer. It serves as one of Qalqilya's main attractions. The zoo houses 170 animals and works closely with zoologists from the Jerusalem Biblical Zoo and the Ramat Gan Safari.[37]

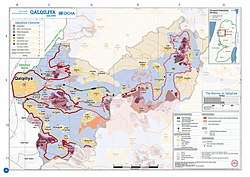

Land usage and the barrier

Of the city's total area of 10,252 dunams, 3,027 were built-up areas, 266 were used for industrial purposes, 2,894 were planted with permanent crops, 419 were used for greenhouses, 274 for livestock ranges, 2,343 were classified as arable, and 283 dunams were occupied by the West Bank barrier. Nearly all of Qalqilya's urban area is under Palestinian civil jurisdiction and Israeli military control (Area B), while 64.7% of the city's municipal territory, mostly agricultural lands and open spaces, is under Israeli civil and military control (Area C).[12]

Israel's construction of the barrier began in 2002 and isolates Qalqilya from the north, west, south, and half of its eastern side, leaving a corridor in the east connecting it with smaller Palestinian villages and hamlets.[12] Israel states its construction of the wall is for security purposes, particularly to prevent infiltration by Palestinian militants into Israel as had occurred during the Second Intifada. The Palestinians state that the barrier is meant to annex Palestinian lands (since the wall often juts deep into Palestinian territory) and control the movement of Palestinians. The barrier has negatively affected Qalqilya's economy, particularly the commercial and trade sectors, because it has separated the city from nearby Palestinian localities and bordering Arab towns in Israel, which contributed about 40% of the city's income prior to the barrier's completion. The barrier has also separated 1,836 dunams of mostly agricultural lands and open spaces within Qalqilya's jurisdiction from the city proper. Social relations between Qalqilya's inhabitants and those of other Palestinian cities have also been hindered by the barrier.[12]

Education

According to the 2007 PCBS census, 95.3% of the inhabitants over the age of 10 were literate. About 75% of the illiterate population were women. The town has 21 public schools, four private schools, three schools managed by UNRWA and 13 kindergartens. All schools are overseen by the Palestinian Ministry of Higher Education. As of 2012, there were 12,286 residents enrolled in school, with 660 teaching staff. In 2007, 10.5% of the population had graduated from an institution of higher education, while 15.7% had completed secondary education, 27.5% preparatory education, 27.4% elementary education and 13.8% had no formal education. There are two colleges in the city: the Ad Da'wa Islamic College established in 1978 and a campus of the Al-Quds Open University established in 1998.[12]

Notable residents

- Waleed Al-Husseini - Writer, Secular Humanist, Founder of Council of Ex-Muslims of France.

- Abu Ali Iyad – Fatah field commander in Jordan and Syria.

References

- "Population, Housing and Establishment Census 2007 : Census Final Results in The West Bank Summary (Population and Housing)" (PDF). Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-12-10. Retrieved 2010-06-16.

- Palmer, 1881, p. 183

- Dani Filc and Hadas Ziv (2006). "Exception as the Norm and the Fiction of Sovereignty: The Lack of the Right to Health Care in the Occupied Territories". In John Parry (ed.). Evil, Law and the State: Perspectives on State Power and Violence. Editions Rodopi B.V. p. 75. ISBN 9789042017481.

- United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs Qalqiliya Closures map for December 2011 Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- "Qalqilya: The Guava Capital" (PDF).

- "Sustainable Development in Qalqiliya, Palestine". reliefweb. 18 April 2016.

- Environmental Profile for the West Bank: Tulkarm District. Applied Research Institute of Jerusalem. p. 76.

- Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 140

- Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 3, Appendix 2, p. 127

- Guérin, 1875, p. 356-357

- Conder and Kitchener, 1882, SWP II, p. 165

- "Qalqilya City Profile" (PDF). Applied Research Institute - Jerusalem. 2013.

- Barron, 1923, Table IX, Sub-district of Tulkarem, p. 27

- Mills, 1932, p. 56

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 21

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 76

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 127

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 177

- Saloul, Ihab (2012). Catastrophe and Exile in the Modern Palestinian Imagination: Telling Memories. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 178.

- Yoav Gelber, Independence Versus Nakba; Kinneret–Zmora-Bitan–Dvir Publishing, 2004, ISBN 965-517-190-6, p.236

- Ben-Yehuda, Hemda; Sandler, Shmuel (February 2012). Arab-Israeli Conflict Transformed, The: Fifty Years of Interstate and Ethnic Crises. SUNY Press. ISBN 9780791489192.

- Brecher, Michael (2017-02-03). Dynamics of the Arab-Israeli Conflict: Past and Present: Intellectual Odyssey II. Springer. ISBN 9783319475752.

- Morris, 1993, pp. 397–399.

- Government of Jordan, Department of Statistics, 1964, p. 8 Archived 2018-01-20 at the Wayback Machine

- Masalha, 2007, 1967: Why Did the Palestinians Leave?

- Morris 2001, p. 328

- Elon 1983, pp. 231–232

- Joel Perlmann. The 1967 Census of the West Bank and Gaza Strip: A Digitized Version. Annandale-on-Hudson, N.Y.: Levy Economics. Institute of Bard College. November 2011 – February 2012. [Digitized from: Israel Central Bureau of Statistics, Census of Population and Housing, 1967 Conducted in the Areas Administered by the IDF, Vols. 1–5 (1967–70), and Census of Population and Housing: East Jerusalem, Parts 1 and 2 (1968–70). http://www.levyinstitute.org/palestinian-census/.] Vol. 1, Table 2.

- Mattar, Phillip (2005). Encyclopedia of the Palestinians. Infobase Publishing. p. 250.

- The Wall (Qalqilya) 2003 Relief Web, Retrieved 10th Dec 2009

- Zitun, Yoav. Hamas network exposed by IDF and Shin Bet in Qalqiliya. Ynet News. 2015-11-10.

- "West Bank city erects memorial to Saddam Hussein". Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- "Palestinian Population by Locality and Refugee Status". Archived from the original on February 7, 2012. Retrieved May 28, 2008.CS1 maint: unfit url (link). 1997 Census. Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS). 1999.

- http://www.pcbs.gov.ps/Downloads/book2364.pdf page 71

- Sharp, Heather (October 16, 2009). "Political struggle over West Bank town".

- Knell, Yolande (2015-01-20). "How Palestinian democracy has failed to flourish". BBC News.

- Splish, splash, new Kalkiya's hippo's takin' a bath, Haaretz

Bibliography

- Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1882). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. 2. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Elon, A. (1983). The Israelis: founders and sons. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-016969-0.

- Government of Jordan, Department of Statistics (1964). First Census of Population and Housing. Volume I: Final Tables; General Characteristics of the Population (PDF).

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945.

- Guérin, V. (1875). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). 2: Samarie, pt. 2. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center.

- Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Morris, B. (1993). Israel's Border Wars, 1949 – 1956. Arab Infiltration, Israeli Retaliation, and the Countdown to the Suez War. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-827850-0.

- Morris, B. (2001). Righteous victims: a history of the Zionist-Arab conflict, 1881-2001. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-679-74475-7.

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

External links

- Welcome To The City of Qalqiliya

- Qalqilya City, Welcome to Palestine

- Qalqiliya City (Fact Sheet), Applied Research Institute–Jerusalem, (ARIJ)

- Qalqiliya City Profile, ARIJ

- Qalqiliya arial photo, ARIJ

- Development Priorities and Needs in Qalqiliya, ARIJ

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 11: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- UNRWA Profile: Qalqilya Town Update 2004 at the Wayback Machine (archived April 14, 2008)