Pyrophone

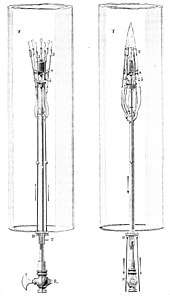

A pyrophone, also known as a "fire/explosion organ" or "fire/explosion calliope" is a musical instrument in which notes are sounded by explosions, or similar forms of rapid combustion, rapid heating, or the like, such as burners in cylindrical glass tubes, creating light and sound. It was invented by physicist and musician Georges Frédéric Eugène Kastner (born 1852 in Strasbourg, France - died 1882 in Bonn, Germany), son of composer Jean-Georges Kastner, around 1870.

.jpg)

Design

It is well known that if a flame of hydrogen gas be introduced within a glass or other tube, and if it be so placed as to be capable of vibrating, there is formed around this flame—that is to say, upon the whole of its enveloping surface—an atmosphere of hydrogen gas, which, in uniting with the oxygen in the air of the tube, burns in small portions, each composed of two parts of hydrogen to one of oxygen, the combustion of this mixture of gases producing a series of slight explosions or detonations.

If such a gaseous mixture, exploding in small portions at a time, be introduced at a point about one-third of the length of the tube from the bottom, and if the number of these detonations be equal to the number of vibrations necessary to produced a sound in the tube, all the acoustic conditions requisite to produce a musical tone are fulfilled.

This sound may be caused to cease either, first, by increasing or reducing the height of the flame, and consequently increasing or diminishing its enveloping surface, so as to make the number of detonations no longer correspond with the number of vibrations necessary to produce a musical sound in the tube, or, secondly, by placing the flame at such a height in the tube as to prevent the vibration of the enveloping film.

— Kastner's patent[2]

Related musical instruments

The pyrophone is similar to the steam calliope, but the difference is that in the calliope the combustion is external to the resonant cavity, whereas the pyrophone is an internal combustion instrument. The difference initially seems insignificant, but external combustion is what gives the calliope its staccatto. Operating under the constant pressures of an external combustion chamber, the calliope merely directs exhaust (HB# 421.22: internal fipple flutes). By controlling the combustion specific to each resonant chamber, the pyrophone has, for better or worse, a greater range of variables in play when producing tones. In a purely mechanical (non-solenoid) calliope, the resulting pressures of external combustion result in between one and five pounds-force (4 and 22 N) of trigger pressure. In a mechanical pyrophone, trigger weight per key is related to comparatively lower backpressure of combustible gas. Again, the force of combustion happens in the resonance chamber; rather than controlling the exhaust of an explosion that has already happened in order to produce tones, the pyrophone controls the explosion to produce the tone.

Pyrophone history

Pyrophones originated in the 19th century. Byron Higgins, using hydrogen burning within the bottom of an open glass tube,[3] first pointed out that if flame is placed in a glass tube sound may be produced in 1777 and in 1818 Michael Faraday attributed the tones to very rapid explosions.[4] Physicist John Tyndall demonstrated that flame(s) in a tube may be made to sound if they are placed close to one third the length of the tube, the explosion occurs at a rate which matches the fundamental or one of the harmonics of the tube, and the volume of the flame is not too great.[1] Brewer, Moigno, and de Parville describe Kastner as having invented the instrument about twenty years before 1890,[5] and he filed a patent on Christmas Eve of 1874.[2][6] Charles Gounod attempted to include the organ in his opera Jeanne d'Arc (1873) and the instrument was shown in the Paris Exhibition (1878).[3] Henry Dunant was a proponent, and Wendelin Weißheimer composed Five Sacred Sonnets for Voice, Flute, Oboe, Clarinet, Pyrophone and Piano (1880).[7]

Pyrophone fuel sources

Pyrophones are usually powered by propane, but gasoline powered mobile units have been built, to connect to automobile fuel intake manifolds and use the spark plugs and wiring, etc., to detonate one or more of the chambers. Hydrogen pyrophones are often made using upside-down glass test tubes as the combustion chambers. Different colors were probably not achieved in Kastner's time, but would be possible with the addition of salts to the flames.[7]

See also

References

- Dunant, Henri (August 1875). . . 7. p. 447 – via Wikisource. Also published with a following discussion in (February 19, 1875). "Description of M. Kastner's New Musical Instrument, the Pyrophone", Journal of the Society of Arts, Volume 23, p.293-7. The Society of Arts. [ISBN unspecified].

- Wade, John (2016). The Ingenious Victorians: Weird and Wonderful Ideas from the Age of Innovation, p.136. Pen and Sword. ISBN 9781473849044.

- "Frederic Kastner obituary", Nature Volume 26, 27 July 1882.

- (November 4, 1882). Scientific American: Supplement, Vol. 14, No. 357, p.5687. New York. [ISBN unspecified].

- E. Cobham Brewer, François-Napoléon-Marie Moigno, and Henri de Parville (1890). "Pyrophone". Hvarför? och Huru? Nyckel till naturvetenskaperna [Swedish: Why? and How?: Key to the natural sciences] – via Project Runeberg.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) [ISBN unspecified]. Trans. from French (in Swedish)

- G.E.F. Kastner, Improvement in Pyrophones, U.S. Patent 164,458, granted June 15, 1875

- Grunenberg, Christoph and Harris, Jonathan; eds. (2005). Summer of Love: Psychedelic Art, Social Crisis and Counterculture in the 1960s, p.186. Liverpool University. ISBN 9780853239291.

Further reading

- Kastner, Georges Frédéric Eugène (1875/1876). "Les Flammes Chantantes". 2008-01-14.. 3rd edition. Paris: E. Dentu. (in French) Publication date 1876

External links

Audio

- Audio samples from Experiment1 Arts Collective at the Wayback Machine (archived 31 January 2012)

Video

- Pyrophone video from Experiment1 Arts Collective at the Wayback Machine (archived 31 January 2012)

Cinema

- Movie "Nothing Like Dreaming" Directed by Nora Jacobson at the Wayback Machine (archived 31 January 2012)