Puff adder

The puff adder (Bitis arietans) is a venomous viper species found in savannah and grasslands from Morocco and western Arabia throughout Africa except for the Sahara and rain forest regions.[2] It is responsible for causing the most snakebite fatalities in Africa owing to various factors, such as its wide distribution, frequent occurrence in highly populated regions, and aggressive disposition.[3][4] Two subspecies are currently recognized, including the nominate subspecies described here.[5]

| Puff adder | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Suborder: | Serpentes |

| Family: | Viperidae |

| Genus: | Bitis |

| Species: | B. arietans |

| Binomial name | |

| Bitis arietans (Merrem, 1820) | |

| |

| Distribution range | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Click to expand

| |

Taxonomy

German naturalist Blasius Merrem described the puff adder in 1820. The word arietans means "striking violently" and is derived from the Latin arieto.[6] The type locality given is "Promontorio bonae spei" (Cape of Good Hope), South Africa.[1]

The species is commonly known as the puff adder,[3][7] African puff adder,[8][9] or common puff adder.[10]

Subspecies

| Subspecies[5] | Taxon author[5] | Common name | Geographic range |

|---|---|---|---|

| B. a arietans | (Merrem, 1820) | African puff adder | Throughout Africa from southern Morocco to Cape Province in South Africa, south-west Arabian Peninsula[3][4] |

| B. a. somalica | Parker, 1949 | Somali puff adder | Somalia, northern Kenya[3] |

Description

The average size is about 1m (39.3 inches) in total length (body + tail) and very stout. Large specimens of 190 cm (75 in) total length, weighing over 6.0 kg (13.2 lbs) and with a girth of 40 cm (16 in) have been reported. Specimens from Saudi Arabia are not as large, usually no more than 80 cm (31 in) in total length. Males are usually larger than females and have relatively longer tails.[3]

The color pattern varies geographically. The head has two well-marked dark bands: one on the crown and the other between the eyes. On the sides of the head, there are two oblique dark bands or bars that run from the eye to the supralabials. Below, the head is yellowish white with scattered dark blotches. Iris color ranges from gold to silver-gray. Dorsally, the ground-color varies from straw yellow, to light brown, to orange or reddish brown. This is overlaid with a pattern of 18–22 backwardly-directed, dark brown to black bands that extend down the back and tail. Usually these bands are roughly chevron-shaped, but may be more U-shaped in some areas. They also form 2–6 light and dark cross-bands on the tail. Some populations are heavily flecked with brown and black, often obscuring other coloration, giving the animal a dusty-brown or blackish appearance. The belly is yellow or white, with a few scattered dark spots. Newborn young have golden head markings with pinkish to reddish ventral plates toward the lateral edges.[3][7]

One unusual specimen, described by Branch and Farrell (1988), from Summer Pride, East London in South Africa, was striped. The pattern consisted of a narrow (1 scale wide) pale yellowish stripe that ran from the crown of the head to the tip of the tail.[3]

Generally, though, these are relatively dull-looking snakes, except for male specimens from highland east Africa and Cape Province, South Africa, that usually have a striking yellow and black color pattern.[7]

Scalation

The head has a less than triangular shape with a blunt and rounded snout. Still, the head is much wider than the neck. The rostral scale is small. The circumorbital ring consists of 10–16 scales. Across the top of the head, there are 7–11 interocular scales. 3–4 scales separate the suboculars and the supralabials. There are 12–17 supralabials and 13–17 sublabials. The first 3–4 sublabials contact the chin shields, of which there is only one pair. Often, there are two fangs on each maxilla and both can be functional.[3][7]

Midbody there are 29–41 rows of dorsal scales. These are strongly keeled except for the outermost rows. The ventral scale count is 123–147, the subcaudals 14–38. Females have no more than 24 subcaudals. The anal scale is single.[3]

Distribution and habitat

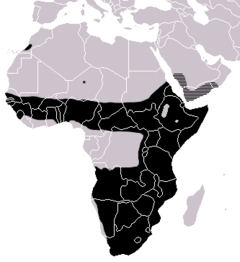

This species is probably the most common and widespread snake in Africa.[3] It is found in most of sub-Saharan Africa south to the Cape of Good Hope, including southern Morocco, Mauritania, Senegal, Mali, southern Algeria, Guinea, Sierra Leone, Côte d'Ivoire, Ghana, Togo, Benin, Niger, Nigeria, Chad, Sudan, Cameroon, Central African Republic, northern, eastern and southern Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda, Kenya, Somalia, Rwanda, Burundi, Tanzania, Angola, Zambia, Malawi, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Botswana, Namibia and South Africa. It also occurs on the Arabian peninsula, where it is found in southwestern Saudi Arabia and Yemen.

It is found in all habitats except true deserts, rain forests, and (tropical) alpine habitats. It is most often associated with rocky grasslands.[12] It is not found in rainforest areas, such as along the coast of West Africa and in Central Africa (i.e., central DR Congo); it is also absent from the Mediterranean coastal region of North Africa. On the Arabian peninsula, it is found as far north as Ta'if.[7] It has been reported to be found in the Dhofar region of southern Oman.[11]

Behaviour

Normally a sluggish species, the puff adder relies on camouflage for protection. Locomotion is primarily rectilinear, using the broad ventral scales in a caterpillar fashion and aided by its own weight for traction. When agitated, it can resort to a typical serpentine movement and move with surprising speed.[3][12] Although mainly terrestrial, these snakes are good swimmers and can also climb with ease; often they are found basking in low bushes. One specimen was found 4.6 m above the ground in a densely branched tree.[3]

If disturbed, they will hiss loudly and continuously, adopting a tightly coiled defensive posture with the forepart of their body held in a taut "S" shape. At the same time, they may attempt to back away from the threat towards cover. They may strike suddenly and fast, to the side as easily as forwards, before returning quickly to the defensive position, ready to strike again. During a strike, the force of the impact is so strong, and the long fangs penetrate so deeply, those prey items are often killed by the physical trauma alone. The fangs apparently can penetrate soft leather.[3][12]

They can strike to a distance of about one-third of their body length, but juveniles will launch their entire bodies forwards in the process. These snakes rarely grip their victims, instead of releasing quickly to return to the striking position.[3]

Feeding

Mostly nocturnal, they rarely forage actively, preferring instead to ambush prey as it happens by. Their prey includes mammals, birds, amphibians like frogs and newts, and lizards.

Reproduction

Females produce a pheromone to attract males, which engage in neck-wrestling combat dances. A female in Malindi was followed by seven males.[4] They give birth to large numbers of offspring: litters of over 80 have been reported, while 50–60 is not unusual. Newborns are 12.5–17.5 cm in length.[12] Very large specimens, particularly those from East Africa, give birth to the highest numbers of offspring. A Kenyan female in a Czech zoo gave birth to 156 young, the largest litter for any species of snake.[4][7]

Captivity

These snakes do well in captivity, but there are reports of gluttony. Kauffeld (1969) mentions that specimens can be maintained for years on only one meal per week, but that when offered all they can eat, the result is often death, or at best wholesale regurgitation.[9] They are bad-tempered snakes and some specimens never settle down in captivity, always hissing and puffing when approached.[4]

Venom

This species is responsible for more snakebite fatalities than any other African snake. This is due to a combination of factors, including its wide distribution, common occurrence, large size, potent venom that is produced in large amounts, long fangs, their habit of basking by footpaths and sitting quietly when approached.[3][4][7]

The venom has cytotoxic effects[13] and is one of the most toxic of any vipers based on LD50.[3] The LD50 values in mice vary: 0.4–2.0 mg/kg IV, 0.9–3.7 mg/kg IP, 4.4–7.7 mg/kg SC.[14] Mallow et al. (2003) give an LD50 range of 1.0–7.75 mg/kg SC. Venom yield is typically between 150–350 mg, with a maximum of 750 mg.[3] Brown (1973) mentions a venom yield of 180–750 mg.[14] About 100 mg is thought to be enough to kill a healthy adult human male, with death occurring after 25 hours.

In humans, bites from this species can produce severe local and systemic symptoms. Based on the degree and type of local effect, bites can be divided into two symptomatic categories: those with little or no surface extravasation, and those with hemorrhages evident as ecchymosis, bleeding and swelling. In both cases there is severe pain and tenderness, but in the latter there is widespread superficial or deep necrosis and compartment syndrome.[15] Serious bites cause limbs to become immovably flexed as a result of significant hemorrhage or coagulation in the affected muscles. Residual induration, however, is rare and usually these areas completely resolve.[3]

Other bite symptoms that may occur in humans include edema, which may become extensive, shock, watery blood oozing from the puncture wounds, nausea and vomiting, subcutaneous bruising, blood blisters that may form rapidly, and a painful swelling of the regional lymph nodes. Swelling usually decreases after a few days, except for the area immediately around the bite site. Hypotension, together with weakness, dizziness and periods of semi- or unconsciousness is also reported.[3]

If not treated carefully, necrosis will spread, causing skin, subcutaneous tissue and muscle to separate from healthy tissue and eventually slough with serous exudate. The slough may be superficial or deep, sometimes down to the bone. Gangrene and secondary infections commonly occurs and can result in loss of digits and limbs.[3][4][7]

The fatality rate highly depends on the severity of the bites and some other factors. Deaths can be exceptional and probably occur in less than 15% of all untreated cases (usually in 2–4 days from complications following blood volume deficit and disseminated intravascular coagulation), although some reports show that severe envenomations have a 52% mortality rate.[2][16] Most fatalities are associated with poor clinical management and neglect.[4][7]

References

- McDiarmid RW, Campbell JA, Touré T. 1999. Snake Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, Volume 1. Herpetologists' League. 511 pp. ISBN 1-893777-00-6 (series). ISBN 1-893777-01-4 (volume).

- U.S. Navy. 1991. Venomous Snakes of the World. US Govt. New York: Dover Publications Inc. 203 pp. ISBN 0-486-26629-X.

- Mallow D, Ludwig D, Nilson G. 2003. True Vipers: Natural History and Toxinology of Old World Vipers. Krieger Publishing Company, Malabar, Florida. 359 pp. ISBN 0-89464-877-2.

- Spawls S, Howell K, Drewes R, Ashe J. 2004. A Field Guide to the Reptiles Of East Africa. A & C Black Publishers Ltd., London. 543 pp. ISBN 0-7136-6817-2.

- "Bitis arietans". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 24 July 2006.

- Chambers Murray Latin-English Dictionary (1976)

- Spawls S, Branch B. 1995. The Dangerous Snakes of Africa. Ralph Curtis Books. Dubai: Oriental Press. 192 pp. ISBN 0-88359-029-8.

- Fichter GS. 1982. Venomous Snakes. (A First Book). Franklin Watts. 66 pp. ISBN 0-531-04349-5.

- Kauffeld C. 1969. Snakes: The Keeper and the Kept. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc. 248 pp. LCCCN 68-27123.

- Bitis arietans at Munich AntiVenom INdex. Accessed 2 August 2007.

- Bitis arietans at the Reptarium.cz Reptile Database. Accessed 2 August 2007.

- Mehrtens JM. 1987. Living Snakes of the World in Color. New York: Sterling Publishers. 480 pp. ISBN 0-8069-6460-X.

- Widgerow AD, Ritz M, Song C. 1994. Load cycling closure of fasciotomies following puff adder bite. European Journal of Plastic Surgery 17: 40-42. Summary at Springerlink. Accessed 31 August 2008.

- Brown JH. 1973. Toxicology and Pharmacology of Venoms from Poisonous Snakes. Springfield, Illinois: Charles C. Thomas. 184 pp. LCCCN 73-229. ISBN 0-398-02808-7.

- Rainer PP, Kaufmann P, Smolle-Juettner FM, Krejs GJ (2010). "Case report: Hyperbaric oxygen in the treatment of puff adder (Bitis arietans) bite". Undersea & Hyperbaric Medicine. 37 (6): 395–398. PMID 21226389. Retrieved 8 January 2012.

- Davidson, Terence. "IMMEDIATE FIRST AID". University of California, San Diego. Archived from the original on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 2011-09-14.

Further reading

- Boulenger GA. 1896. Catalogue of the Snakes in the British Museum (Natural History). Volume III., Containing the...Viperidæ. London: Trustees of the British Museum (Natural History). (Taylor and Francis, printers.) xiv + 727 pp. + Plates I.- XXV. (Bitis arietans, pp. 493–495.)

- Branch, Bill. 2004. Field Guide to Snakes and Other Reptiles of Southern Africa. Third Revised edition, Second impression. Sanibel Island, Florida: Ralph Curtis Books. 399 pp. ISBN 0-88359-042-5. (Bitis arietans, pp. 114–115 + Plates 3, 12.)

- Broadley DG, Cock EV. 1975. Snakes of Rhodesia. Zimbabwe: Longman Zimbabwe Ltd. 97 pp.

- Broadley DG. 1990. FitzSimons' Snakes of Southern Africa. Parklands (South Africa): J Ball & AD Donker Publishers. 387 pp.

- Merrem B. 1820. Versuch eines Systems der Amphibien: Tentamen Systematis Amphibiorum. J.C. Krieger. Marburg. xv + 191 pp. + 1 plate.

("Vipera. Echidna. arietans", p. 152.) - Pienaar U de V. 1978. The reptile fauna of Kruger National Park. National Parks Board of South Africa. 19 pp.

- Sweeney RCH. 1961. Snakes of Nyasaland. Zomba, Nyasaland: The Nyasaland Society and Nyasaland Government. 74 pp.

- Turner RM. 1972. Snake bite treatment. Black Lechwe 10 (3): 24–33.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bitis arietans. |

- Video of B. g. gabonica and B. arietans. on YouTube Accessed 9 December 2006.

- Video of two puff adders: B. a. arietans and B. a. somalica. on YouTube. Accessed 1 March 2007.

- Image of B. arietans bite that resulted in fasciotomy at South African Vaccine Producers. Accessed 26 July 2008.

- Birds mob Puff Adder - paper in ejournal Ornithological Observations