Carl W. Ackerman

Carl William Ackerman (January 16, 1890 in Richmond, Indiana[1] – October 9, 1970 in New York City)[2] was an American journalist, author and educational administrator, the first dean of the Columbia School of Journalism. In 1919, as a correspondent of the Public Ledger of Philadelphia, he published the first excerpts of an English translation of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion but changed the text so that it appeared to be a Bolshevik tract.

Carl W. Ackerman | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | January 16, 1890 |

| Died | October 9, 1970 (aged 80) |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Earlham College |

| Occupation | Journalist |

| Known for | Public Ledger; School of Journalism at Columbia University |

In 1931, he was appointed as the director of the journalism department, succeeding John William Cunliffe, and became the first dean of the newly-established graduate School of Journalism program at Columbia University.[3] He was instrumental in developing the school through its first two decades, as he served in that position until 1954.

Career as a journalist

Ackerman graduated from Earlham College and worked as a correspondent in World War I with the United Press. He first gained public attention with his book, Germany, The Next Republic? (1917), which discussed the possibility of a successful democracy in post-Kaiser Germany.[4] At the time, during World War I, his position was considered quite radical.

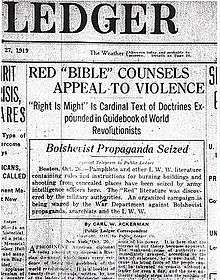

Ackerman became a journalist with the Philadelphia Public Ledger. In 1919, he published articles headlined as "The Red Bible" that featured the first English edition of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, an anti-Semitic hoax that had been published in Europe and recounted a Jewish plan for world domination. By replacing all the references to Jews with references to Bolsheviks, he turned it into an anti-Bolshevik hoax.[5]

Marriage and family

Ackerman married Mabel VanderHoof in 1914. They had one son, Robert VanderHoof Ackerman, who was born in 1915 when Ackerman was living in Berlin as a correspondent for the United Press Associations during World War I.[6]

Academic career

In 1931 Ackerman was recruited to serve as the director and, later, as the first dean, of Columbia University's School of Journalism graduate program. The Journalism Department was established in 191w by an estate gift of Joseph Pulitzer, a major publisher in Saint Louis and New York City. The philanthropist's money was also used to establish the Pulitzer Prize awards in journalism, literature, drama and music.

Ackerman was a provocative figure; for instance, he accused the administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt of fascism, and attempts to control journalism.[7] Known to be reclusive, he worked to establish the school as one of the foremost schools of journalism in the nation.

He served on the board of trustees for Science Service, now known as Society for Science & the Public, from 1936-1938.

In 1954, after the death of his wife, Ackerman notified the university of his intention to resign, and after Columbia had found a replacement, he did so. He was known to visit the university only occasionally until his death in New York, New York in 1970.

References

- Myers, William Starr (2000). Prominent Families of New Jersey. Volume 1 by William Starr Myers. ISBN 9780806350363.

- Ohles, Frederik; Ohles, Shirley G.; Ohles, Shirley M.; Ramsay, John G. (1997). Biographical Dictionary of Modern American Educators. google.it. ISBN 9780313291333.

- https://journalism.columbia.edu/columbia-journalism-school

- "Germany, The Next Republic?". Project Gutenberg.

- Toczek, Nick (2015). Haters, Baiters and Would-Be Dictators: Anti-Semitism and the UK Far Right. Routledge. ISBN 978-1317525875.

- "Carl W. Ackerman Papers". infomotions.com. Retrieved July 2, 2014.

- "Carl W. Ackerman", Columbia Alumni Magazine, Spring 2005

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carl W. Ackerman. |

- Works by Carl W. Ackerman at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Carl W. Ackerman at Internet Archive

- Images of Ackerman at Columbia Alumni Magazine, Spring 2005: , , , , .