Darwin's rhea

Darwin's rhea (Rhea pennata), also known as the lesser rhea, is a large flightless bird, but the smaller of the two extant species of rheas. It is found in the Altiplano and Patagonia in South America.

| Darwin's rhea | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| At Zurich Zoo, Switzerland | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Rheiformes |

| Family: | Rheidae |

| Genus: | Rhea |

| Species: | R. pennata |

| Binomial name | |

| Rhea pennata | |

| Subspecies | |

|

R. p. garleppi (Chubb, 1913)[3] | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Rhea macrorhyncha | |

Description

The lesser rhea stands at 90 to 100 cm (35–39 in) tall. Length is 92 to 100 cm (36–39 in) and weight is 15 to 28.6 kg (33–63 lb).[2][5] Like most ratites, it has a small head and a small bill, the latter measuring 6.2 to 9.2 cm (2.4 to 3.6 in), but has long legs and a long neck. It has relatively larger wings than other ratites, enabling it to run particularly well. It can reach speeds of 60 km/h (37 mph), enabling it to outrun predators. The sharp claws on the toes are effective weapons. Their feathers are similar to those of ostriches, in that they have no aftershaft.[6] Their plumage is spotted brown and white, and the upper part of their tarsus is feathered.[2] The tarsus is 28 to 32 cm (11 to 13 in) long and has 18 horizontal plates on the front.[2]

Etymology

It is known as ñandú petiso, or ñandú del norte, in Argentina, where the majority live. Other names are suri and choique. The name ñandú comes from the greater rhea's name in Guaraní, ñandú guazu, meaning big spider, possibly in relation to their habit of alternately opening and lowering their wings when they run. In English, Darwin's rhea gets its scientific name from Rhea, a Greek goddess, and pennata, meaning winged. The specific name was bestowed in 1834 by Darwin's contemporary and rival Alcide d'Orbigny, who first described the bird to Europeans from a specimen from the lower Río Negro south of Buenos Aires, Argentina.[2][7] As late as 2008, it was classified in the monotypic genus Pterocnemia. This word is formed from two Greek words pteron, meaning feathers, and knēmē, meaning the leg between the knee and the ankle, hence feather-legged, alluding to their feathers that cover the top part of the leg.[8] In 2008, the SACC subsumed Pterocnemia into the genus Rhea.[9]

Taxonomy

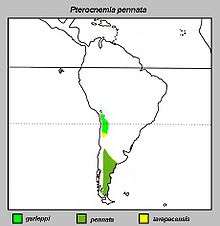

Three subspecies have traditionally been recognized:

- R. p. garleppi is found in the puna of southeastern Peru, southwestern Bolivia, and northwestern Argentina.[10]

- R. p. tarapacensis is found in the puna of northern Chile from the region of Arica and Parinacota to Antofagasta.[11]

- R. p. pennata is found in the Patagonian steppes of Argentina and Chile.[1][10]

The IUCN considers the former two northern taxa R. p. tarapacensis and R. p. garleppi as a separate species, the puna rhea (R. tarapacensis).[12][11] Both garleppi and tarapacensis were described by Charles Chubb in 1913.[3] It is possible garleppi should be considered a junior synonym of tarapacensis.

Behavior

The lesser rhea is mainly a herbivore, with the odd small animal (lizards, beetles, grasshoppers) eaten on occasion. It predominately eats saltbush and fruits from cacti, as well as grasses.[2] They tend to be quiet birds, except as chicks when they whistle mournfully, and as males looking for a female, when they emit a booming call.[2]

The males of this species become aggressive once they are incubating eggs. The females thus lay the later eggs near the nest, rather than in it. Most of the eggs are moved into the nest by the male, but some remain outside, where they rot and attract flies. The male, and later the chicks, eat these flies. The incubation period is 30–44 days, and the clutch size is from 5–55 eggs. The eggs are 87 to 126 mm (3.4–5.0 in) and are greenish yellow.[2] Chicks mature by three years of age. Outside the breeding season, Darwin's rhea is quite sociable: it lives in groups of from 5 to 30 birds, of both sexes and a variety of ages.[2]

Distribution and habitat

Darwin's rhea lives in areas of open scrub in the grasslands of Patagonia and on the Andean plateau (the Altiplano), through the countries of Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, and Peru.[1] All subspecies prefer grasslands, brushlands and marshland. However, the nominate subspecies prefers elevations less than 1,500 m (4,900 ft),[1] where the other subspecies typically range from 3,000 to 4,500 m (9,800–14,800 ft), but locally down to 1,220 m (4,000 ft) in the south.[12]

History of the discovery of the genus Rhea

During the second voyage of HMS Beagle, the young naturalist Charles Darwin made many trips on land, and around August 1833 heard from gauchos in the Río Negro area of Northern Patagonia about the existence of a smaller rhea, "a very rare bird which they called the Avestruz Petise". He continued searching fruitlessly for this bird, and the Beagle sailed south, putting in at Port Desire in southern Patagonia on 23 December. On the following day, Darwin shot a guanaco which provided them with a Christmas meal, and in the first days of January, the artist Conrad Martens shot a rhea which they enjoyed eating before Darwin realised that this was the elusive smaller rhea rather than a juvenile, and preserved the head, neck, legs, one wing, and many of the larger feathers. As with his other collections, these were sent to John Stevens Henslow in Cambridge. On 26 January, the Beagle entered the Straits of Magellan and at St. Gregory's Bay Darwin met Patagonians he described as "excellent practical naturalists". A half Indian, who had been born in the Northern Provinces, told him that the smaller rheas were the only species this far south, while the larger rheas kept to the north. On an expedition up the Santa Cruz River, they saw several of the smaller rheas, which were too wary to be approached closely or caught.[13][14]

In 1837, Darwin's rhea was described as Rhea darwinii (later synomized with R. pennata) by the ornithologist John Gould in a presentation to the Zoological Society of London in which he was followed by Darwin reading a paper on the eggs and distribution of the two species of rheas.[15]

When Gould classified Darwin's rhea and the greater rhea as separate species, he confirmed a serious problem for Darwin. These birds mainly live in different parts of Patagonia, but there is also an overlapping zone where the two species coexist. As every living being had been created in a fixed form, as accepted by the science of his time, they could only change their appearance by a perfect adaptation to their way of life, but would still be the same species. But now he had to deal with two different species. This started to form his idea that species were not fixed at all, but that another mechanism might be at work.[16]

Conservation

Darwin's rhea is categorized as least concern by the IUCN.[1] The former southern nominate subspecies remains relatively widespread and locally fairly common. Its range is estimated at 859,000 km2 (332,000 sq mi).[1] The situation for the two former northern subspecies is more worrying, with their combined population estimated as being possibly as low as in the hundreds.[12] However, they are classified as Rhea tarapacensis by the IUCN, which regards it as being near threatened, with the primary threats being hunting, egg-collecting, and fragmentation of its habitat due to conversion to farmland or pastures for cattle-grazing.[12][2]

Footnotes

- Birdlife International (2018)

- Davies, S.J.J.F. (2003)

- Brands, S. (2008)

- Peters, James L. (1979)

- Elliott, Andrew (1992)

- Perrins, C. (1987)

- Krulwich, R. (2009)

- Gotch, A.T. (1995)

- Nores, M. (2008)

- Clements, J (2007)

- Jaramillo et al. (2003)

- Birdlife International (2016)

- Barlow 1963, pp. 271–5.

- Keynes 2001, pp. 212, 217–218

- Darwin, C (1837)

- Herbert, S (1980)

References

- BirdLife International (2018). "Rhea pennata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T22728199A132179491. Retrieved 15 February 2020.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- BirdLife International (2016). "Rhea tarapacensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22728206A94974751. Retrieved 15 February 2020.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- BirdLife International (2008b). "Lesser Rhea - BirdLife Species Factsheet". Data Zone. Retrieved 6 February 2009.

- Brands, Sheila (14 August 2008). "Systema Naturae 2000 / Classification, Rhea pennata". Project: The Taxonomicon. Archived from the original on 13 March 2010. Retrieved 4 February 2009.

- Clements, James (2007). The Clements Checklist of the Birds of the World (6th ed.). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-4501-9.

- Darwin, Charles (1837). "Notes on Rhea americana and Rhea darwinii". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 5 (51): 35–36.

- Davies, S.J.J.F. (2003). "Rheas". In Hutchins, Michael (ed.). Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. 8 Birds I Tinamous and Ratites to Hoatzins (2nd ed.). Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group. pp. 69–74. ISBN 0-7876-5784-0.

- Elliott, Andrew (1992). "Lesser Rhea". In Hoyo, Joseph del (ed.). Handbook of the Birds of the World. 1 (Ostrich to Ducks). Lynx Edicions. ISBN 978-8487334108.

- Gotch, A.F. (1995) [1979]. "15". Latin Names Explained. A Guide to the Scientific Classifications of Reptiles, Birds & Mammals. London: Facts on File. p. 176. ISBN 0-8160-3377-3.

- Herbert, Sandra (1980). "The Red Notebook of Charles Darwin". Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History). 7: 1–164.

- Jaramillo, Alvaro; Burke, Peter; Beadle, David (2003). Birds of Chile. London: Christopher Helm. ISBN 0-7136-4688-8.

- Keynes, Richard (2001), Charles Darwin's Beagle Diary, Cambridge University Press, retrieved 1 August 2019

- Krulwich, Robert (24 February 2009). "Darwin's Very Bad Day: 'Oops, We Just Ate It!'". National Public Radio. Retrieved 6 June 2009.

- La Caledonia Sur. "The revered bird of native people". Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- Nores, Manuel (7 August 2008). "Incluir Pterocnemia dentro de Rhea". South American Classification Committee. American Ornithologists' Union. Archived from the original on 20 September 2008. Retrieved 4 February 2009.

- Perrins, Christopher (1987) [1979]. Harrison, C.J.O. (ed.). Birds: Their Lifes, Their Ways, Their World. Pleasantville, NY, US: Reader's Digest Association, Inc. pp. 168–170. ISBN 0895770652.

- Peters, James Lee (1979). Checklist of Birds of the World (PDF). 1 (2nd ed.). Cambridge, MA: Museum of Comparative Zoology. pp. 6–7.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rhea pennata. |