Providensky District

Providensky District (Russian: Провиде́нский райо́н; Chukchi: Урэлӄуйым район) is an administrative[1] and municipal[9] district (raion), one of the six in Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, Russia. It is located in the northeast of the autonomous okrug, in the southern half of the Chukchi Peninsula with a northwest extension reaching almost to the Kolyuchinskaya Bay on the Arctic. It borders with Chukotsky District in the north, the Bering Sea in the east and south, and with Iultinsky District in the west. The area of the district is 26,800 square kilometers (10,300 sq mi).[4] Its administrative center is the urban locality (an urban-type settlement) of Provideniya.[1] Population: 3,923 (2010 Census);[5] 4,660 (2002 Census);[11] 9,778 (1989 Census).[12] The population of Provideniya accounts for 50.2% of the district's total population.[5]

Providensky District Провиденский район | |

|---|---|

Road to Novoye Chaplino in Providensky District | |

.png) Flag  Coat of arms | |

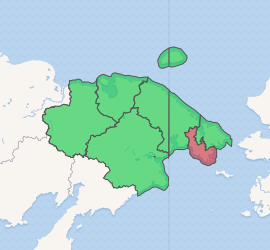

Location of Providensky District in Chukotka Autonomous Okrug | |

| Coordinates: 64°27′N 173°15′W | |

| Country | Russia |

| Federal subject | Chukotka Autonomous Okrug[1] |

| Established | April 25, 1957[2] |

| Administrative center | Provideniya[1] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Local government |

| • Head of Administration[3] | Sergey Shestopalov (acting)[3] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 26,800 km2 (10,300 sq mi) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 3,923 |

| • Estimate (2018)[6] | 3,695 (-5.8%) |

| • Density | 0.15/km2 (0.38/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 50.2% |

| • Rural | 49.8% |

| Administrative structure | |

| • Inhabited localities[7] | 1 Urban-type settlements[8], 5 Rural localities |

| Municipal structure | |

| • Municipally incorporated as | Providensky Municipal District[9] |

| • Municipal divisions[9] | 1 Urban settlements, 3 Rural settlements |

| Time zone | UTC+12 (MSK+9 |

| OKTMO ID | 77710000 |

| Website | http://www.provadm.ru |

Geography

The district lies in a mountainous region, with most of its inhabited localities found on the coast. Wetlands occupy the territory between mountain ranges and close to the shore near inlets and brackish lagoons.[13] The southern section of the coastline is approximately 850 kilometers (530 mi).[13] About a quarter of this consists of beaches and gravel spits with the remainder consisting of rugged, rocky coastline containing numerous fjords.[13]

History

Prehistory

The history of human existence in what would become Providensky District can be traced back to the Paleolithic age, when hunter-gatherers lived in the area.[14] Over the next few millennia, the hunters-gatherers split into two groups, with one staying in the tundra and the other moving closer to the sea for food.

Gradually, those who settled by the shore began to develop their own individual culture, including the construction of their homes and other buildings using whale bones as support, structures which would later develop into the yarangas.[14] Excavations at many sites along the coast of the district, including present-day localities such as Enmelen, Nunligran, Yanrakynnot, and Sireniki, indicate an abundance of food as well as indicating a considerable degree of continuity in terms of indigenous settlement.[14] As a result, the southeastern part of the coast is home to a large number of Beringian monuments and archaeological sites, with the area around Arakamchechen Island, Yttygran Island, and the Senyavin Straits having been given protected area status as part of the Beringia Park.[13] Providensky District also includes Yttygran Island, which features an area known as "Whale Bone Alley", where the jaw bones and ribs of Bowhead whales are arranged on the beach. There is also a large, permanent polynya near Sireniki.

17th–19th centuries

In the 17th century, Semyon Dezhnyov and his Cossacks founded the ostrog (fortress) of Anadyrsk and began to explore Chukotka. One expedition, led by Dezhnyov's successor Kurbat Ivanov, resulted in the discovery of the Provideniya Bay,[14] although the bay did not receive this name until it was "re-discovered" by Captain Thomas E. L. Moore[15] in 1848. Vitus Bering discovered the Preobrazheniye Bay on his first Kamchatka expedition[14] in 1728.

In the 18th century, further inland exploration was performed by Joseph Billings under orders from Catherine the Great to explore her new land of Chukotka and to negotiate trade between Russians and Chukchi, something the Chukchi were pleased to do, since Anadyrsk, which had previously been the center for trade between the Russians and the local indigenous peoples, had closed and the Chukchi needed Russian goods.[14]

Further exploration took place during the 19th century, when Fyodor Litke, the Arctic explorer, discovered and mapped the Senyavin Strait, the body of water that separates Arakamchechen Island, on which the rural locality of Yanrakynnot is found, from the mainland.[14]

20th century

Providenskaya Volost was founded in 1923 as a part of Chukotsky Uyezd.[14] The administrative center Provideniya—the largest inhabited locality east of Anadyr—was established in the 1930s as the port to serve the eastern end of the Northern Sea Route. The port stands on the Komsomolskaya Bay (named after the Soviet Komsomol youth organization), a branch of the much larger Provideniya Bay, providing a suitable deep water harbor for Russian ships, close to the southern limits of the winter ice fields.

In its present form, the district was founded on April 25, 1957 by splitting its territory from the territory of Chukotsky District.[2]

Historical sites in Providensky District

Although there is a large number of ancient settlements and sites spread across the whole of Chukotka, a particularly high number of such sites is located in Providensky District. These sites range from the stone-age sites, to sites originally established in the Middle Ages, which continued to be populated into the 20th century. A large number of these, like many indigenous settlements still extant in the beginning of the 20th century, were closed as a result of Soviet collectivization policies.[16] Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, a number of these settlements have been repopulated by indigenous people looking to regain use of traditional hunting areas.[16]

Scene from Yanrakynnot |

Aerial view of the Penkigney Bay, near to several ancient sites in Providensky District |

Ceremonial whale bones, Whale Bone Alley, Yttygran Island. |

The table below outlines some of the more significant historical site in Providensky District

| Name of Historical Site | Comments |

|---|---|

| Avan |

Also known as Eunmon, Estikhet, and Estiget[17] and located about an hour from Provideniya, this site is a Yupik village first established in the 13th century and occupied through the 20th century.[14] It was located at the foot of East Head (Estikhet in Yupik) by Moore Lake (Nayvaq Estikhet Lagoon)[18] The site contains a number of yarangas as well as a "klegran"—a building used only by the men of the village.[14] The area is still a popular place with local people from Provideniya.[19] The site contains a cultural layer several meters deep and there are a number of abandoned underground dwellings.[20] In 1927, Avan was one of the largest Yupik whaling settlements and had a population of seventy-seven.[20] It was abolished in 1942.[18][20] |

| Chelkun |

Also known as Kelkun,[20] this site is a Neolithic campsite located where the Chelkun and Ioniveyem Rivers meet.[14] It was first excavated in 1979.[14] The settlers of Chelkun were some of the founders of Novoye Chaplino.[19] In 1927, its population was twelve and it was under the administration of Kivaksky Selsoviet.[20] |

| Gylmymyl |

This was a small settlement on the mainland of Chukotka, in the Gylmymyl Bay, facing Arakamchechen Island. In 1927, its population was twenty.[20] Gylmymyl served as the administrative center of a selsoviet, which extended over a number of other nearby rural localities, including Kalkhtyunay (population in 1927 - 28), Kelkun (population in 1927 - 19), Nutenut(population in 1927 - 26), and Epiliki (population in 1927 - 18).[20] |

| Kivak |

This is an ancient village, approximately 2000 years old, founded during the time of the Bering Sea culture.[14] Its name literally means "green glade" in Chukchi[14] and its inhabitants also were some of the founders of Novoye Chaplino.[19][20] In 1927, Kivak had a population of sixty-six, which grew to ninety-two by 1950.[20] Today, the remains of the village are being eroded by the sea, as well as being stripped by people living in the area.[20] |

| Kurgu |

Pre-historic site. This is the only Eskimo village with underground dwellings located in a gorge secluded from the sea.[20] |

| Kurupka |

Also known as Kurupkaq, Kurupkan, a small settlement inland of 69 people in 1927, that grew to 102 by 1943.[20] The inhabitants here spoke the Sirenik Eskimo language.[18] |

| Kyngynin |

Also known as Kenilgan,[20] Kyga,[21] and Kygynin[21] this site on the northeast coast of Arakamchechen Island, on Cape Kygynin, is linked with the Whale Bone Alley on Yttygran Island and consists of a series of whale bone columns pointing in the direction of Whale Bone Alley, two burial mounds, and a ring of boulders.[14] It is the southernmost settlement where the population engaged in hunting the Gray whale.[21] In 1927, it had a population of twenty-eight.[20] It is thought that Ekkr, the last east Chukotkan sea shaman, may have lived here in the 1940s.[20] This area contains a variety of settlements of different ages, indicating that the region had been inhabited for a considerable amount of time.[21] The exposed nature of the coast of Arakamchechen Island has led to considerable erosion, destroying much of the oldest remains, though the remains of abandoned subterranean houses and meat pits made of whale bones constructed to act as a sort of freezer can still be seen.[21] |

| Masik |

Also called Masiq, Mechigment, and Agritkino,[20] Masik is the site of what was once a very sizable village, even by modern-day Chukotkan standards, stretching over a mile in length[14] and forming two large ovals in plan around two now dry lakes.[22] The site also contains a very large number of well-preserved structures including homes, yarangas, whale bone structures for drying boats, and storage facilities.[14] The village was populated from the 12th to the mid-20th century, although there is evidence to suggest that different parts of the settlement were inhabited at different times in its history.[14] The village was based on the southern spit at the entrance to Mechigmen Bay.[18][20] The village economy was driven mainly by the hunting of Bowhead and Grey Whales.[20] |

| Naivan |

This is a fortified site from the Mesolithic near Cape Chaplino consisting of the remains of a number of yarangas and a fortified settlement about 3 kilometers (1.9 mi) away at Guygungu.[14] |

| Puturak |

The name is derived from the word putulyk, meaning "meandering" in Yupik, and the place is an early-Holocene workshop site that was excavated in 1993.[14] |

| Rygnakhpak |

Rygnakhpak is a curious fortified settlement consisting of cells created from large boulders on the upper slopes of Mount Rygnakhpak, an old volcano.[14] In addition to the old cells, there is also a more modern structure, which is thought to date from the Cold War days, when local people would have had to man the station to keep a look out for invading armies.[14] Similar structures are found along the coast between this point and Enurmino. |

| Singak |

Also known as Singhaq. Under the Soviet government several Eskimo families lived in Yarangas (reindeer skin tents) near the whalebone posts. A field of stone cairns/lay-outs was discovered, the field was surrounded by one row of stone wall. Judging by the remains of subterranean huts made of bones of young bowhead whales Sinrak used to be the biggest whaling village. The people of the village specialized in hunting bowhead whale calves. Krupnik thinks that the village was abandoned at the end of the 18th – beginning of the 19th century.[20] |

| Ulkhum |

Like Puturak, this is another early-Holocene site. Its name is derived from the Yupik word ulkhuk, meaning "hot springs". Ulkhum is a thermal spring site still used today by local people.[14] Though it has somewhat fallen into disrepair, it is said that the radon baths here have the power to help heal wounds and to cure skin ailments and lower back pain.[14] |

| Ungazik |

Also known as Ungayiq, Chaplino, Unyyn, and Indian Point,[20] Unazik is another locality that provided the first inhabitants of Novoye Chaplino.[19] Its name is derived from the Yupik word for "bewhiskered". Unazik was inhabited until the mid-20th century prior to it being evacuated due to erosion by the sea,[20] and the buildings were pulled down in 1958–1960.[14] Prior to the evacuation, Unazik was a large village, even by modern-day Chukotkan standards, with a population of around five hundred and a reputation as an important local trading and whaling center.[14] In 1927, the population was 254, had increased to 296 in 1943, mainly due to the abandonment of the neighboring village of Tyfliak, further north up the coast,[20] though had fallen by 1950 to only 206.[20] Chaplino was the largest settlement in the area and was a focal point for trade with America in the pre-Soviet era, when it was known as Indian Point.[20] |

| Whale Bone Alley |

Situated on the northern shore of Yttygran Island (from the Chukchi word etgyran, meaning "midway dwellings"), the Whale Bone Alley consists of a large number of carefully arranged whale skulls, whale bones and stones, along with a considerable number of meat storage pits.[14] It is thought that the Whale Bone Alley was used as a central shrine by a number of different villages dotted along the eastern Chukotkan coast.[23] It is also thought that the site was used for initiation rituals and for sporting contests,[23] although the local Yupik have a simpler explanation that the island was a collective center for the flensing, butchery, and storage of whale meat—an idea supported by the etymology of the Yupik name for Yttygran: Sikliuk, from siklyugak, meaning "meat pit" in Yupik.[14] There used to be a village nearby the main monumental location called Sikliuk (also known as Siqluk and Sekliuk).[20] In 1927, this village had a population of forty-five.[20] It was abolished in 1950.[18][20] The site is monumental by Chukotkan standards when compared with other early settlements such as Uelen, Ekven, Sireniki, and Kivak, and consists of several lines of whale skulls and jaw bones along the shoreline, several large pits behind them, and a number of meat pits surrounding a central sanctuary and stone path around one third of the way along the site traveling from south to north.[22] The site extends some 1,800 feet (550 m) along the northern coast of Yttygran Island[24] and lies on a major whale migration path.[23] It is thought that the site was chosen partly because of the ease by which local people could kill and butcher a whale and also as a place where people could come together and trade on neutral ground in a forerunner to the fairs held during the period of Cossack exploration of the region.[14] There is no evidence of any monumental ritual center like this elsewhere in any other part of Eskimo lands, though there are sites along the Chukotkan coast where the whale skull motifs can be seen at sites such as Nykhsirak.[22] |

Demographics

As is typical in Chukotka, the majority of the population lives in the district's main urban center, in this case Provideniya, and the immediate surrounding area. As in Chukotsky District, the isolation of this area, even by Chukotkan standards, means that there is a significantly higher percentage of indigenous inhabitants than in many of the other districts in the autonomous okrug, with the Chukchi the dominant indigenous group in the District.[25] About 55% of the population are reported as being of specifically Chukchi origin.

Economy

Although the district has an urban center and port in Provideniya, the economy, thanks to the high indigenous population, is still centered around traditional agriculture, marine hunting (for gray and beluga whales)[13] and fishing (for sockeye salmon, chum, Arctic char, and Arctic cod)[13] as well as associated crafts. Reindeer herding is also a major source of income,[13] even though the total number of reindeer in the district, 1,202, is substantially smaller than in some of the larger districts in the autonomous okrug. In order to encourage the continuation of this type of economy, there is a training college for reindeer herders in Provideniya. Future plans for the district include continuing to grow reindeer farming and related enterprises as well as developing seal fisheries.

Provideniya is described as "the largest Russian port in the Western Hemisphere".[13] The importance of Provideniya as a port decreased in the 1990s following a decrease of traffic on the Northern Sea Route, although it is still used as the arrival point for American tourists arriving from Nome.[13]

Transportation

Along with the port, the district is also served by the Provideniya Bay Airport, where Chukotavia provide flights to Anadyr. The airport has played a significant role in developing relations with the United States since the dissolution of the Soviet Union in the late 1980s, with Alaska Air flights to Provideniya regularly occurring throughout the 1990s.

Administrative and municipal status

Within the framework of administrative divisions, Providensky District is one of the six in the autonomous okrug.[1] The urban-type settlement of Provideniya serves as its administrative center.[1] The district does not have any lower-level administrative divisions and has administrative jurisdiction over one urban-type settlement and five rural localities.

As a municipal division, the district is incorporated as Providensky Municipal District and is divided into one urban settlement and three rural settlements.[9]

Inhabited localities

| Urban settlements | Population | Male | Female | Inhabited localities in jurisdiction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provideniya (Провидения) |

2756[26] | 1403 (50.9%) | 1455 (49.1%) |

|

| Rural settlements | Population | Male | Female | Rural localities in jurisdiction* |

| Enmelen (Энмелен) |

367 | 188 (51.2%) | 179 (48.8%) | |

| Nunligran (Нунлигран) |

360 | 191 (53.1%) | 169 (46.9%) |

|

| Yanrakynnot (Янракыннот) |

338 | 185 (54.7%) | 153 (45.3%) |

|

Divisional source:[9]

Population source:[5]

*Administrative centers are shown in bold

References

Notes

- Law #33-OZ

- Official website of Providensky District. About the district Archived June 9, 2013, at WebCite (in Russian)

- Official website of Providensky District. Local Self-Government of Providensky Municipal District Archived November 26, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- О муниципалитете - Провиденский городской округ

- Russian Federal State Statistics Service (2011). "Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года. Том 1" [2010 All-Russian Population Census, vol. 1]. Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года [2010 All-Russia Population Census] (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service.

- "26. Численность постоянного населения Российской Федерации по муниципальным образованиям на 1 января 2018 года". Federal State Statistics Service. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- Directive #517-rp

- The count of urban-type settlements may include the work settlements, the resort settlements, the suburban (dacha) settlements, as well as urban-type settlements proper.

- Law #45-OZ

- "Об исчислении времени". Официальный интернет-портал правовой информации (in Russian). June 3, 2011. Retrieved January 19, 2019.

- Russian Federal State Statistics Service (May 21, 2004). "Численность населения России, субъектов Российской Федерации в составе федеральных округов, районов, городских поселений, сельских населённых пунктов – районных центров и сельских населённых пунктов с населением 3 тысячи и более человек" [Population of Russia, Its Federal Districts, Federal Subjects, Districts, Urban Localities, Rural Localities—Administrative Centers, and Rural Localities with Population of Over 3,000] (XLS). Всероссийская перепись населения 2002 года [All-Russia Population Census of 2002] (in Russian).

- "Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 г. Численность наличного населения союзных и автономных республик, автономных областей и округов, краёв, областей, районов, городских поселений и сёл-райцентров" [All Union Population Census of 1989: Present Population of Union and Autonomous Republics, Autonomous Oblasts and Okrugs, Krais, Oblasts, Districts, Urban Settlements, and Villages Serving as District Administrative Centers]. Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 года [All-Union Population Census of 1989] (in Russian). Институт демографии Национального исследовательского университета: Высшая школа экономики [Institute of Demography at the National Research University: Higher School of Economics]. 1989 – via Demoscope Weekly.

- A. V. Andreev. Wetlands in Northeastern Russia Archived July 28, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Wetlands in Russia, Volume 4, Moscow, 2004, p. 14

- Fute, pp. 129ff

- Bob Gal. Beringia Days, 2008 (abstract) Archived September 29, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. 2008 Alaska Park Science Symposium.

- Moved by the State and Left Behind: Histories of village relocations in Chukotka, Russia, Holzlehner, T., University of Alaska. Boreas: MOVE, part of the International Polar Year Scientific Program

- Provideniya Museum Catalogue, p. 133

- Naukan Yupik Eskimo Dictionary, Jacobsen S. A., Krauss M., Dobrieva E. A., Golovko E. A., Alaska Native Language Center, 2004

- Official website of the Beringia Park. Area of Novoye Chaplino Archived June 10, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- Beringian Notes 2.2, Bogoslovaskaya, L., National Park Service, Alaska Region (1993), pp. 1-12

- Provideniya Museum Catalogue, p. 135

- M. A. Chelnov and I. I. Krupnik. Whale Alley: A Site on the Chukchi Peninsula, Siberia. Expedition, University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 6ff

- S. I. Arutyunov, I. I. Krupnik, and M. A. Chelnov. Whale Alley: the Antiquities of the Senyavin Strait Islands. Moscow: Nauka.

- S. W. Fair. Alaska Native Art: Tradition, Innovation, Continuity. University of Alaska Press, p. 45

- Norwegian Polar Institute. Indigenous Peoples of the north of the Russian Federation, Map 3.6

- This figure includes the census results for Provideniya, Novoye Chaplino and Sireniki. The results of the 2010 Census are given for Provideniya Urban Settlement, Novoye Chaplino Rural Settlement and Sireniki Rural Settlement, both former municipal formations of Providensky Municipal District. According to Law #45-OZ, Novoye Chaplino and Sireniki were the only inhabited localities on the territory of their respective Rural Settlements prior to the merger.

Sources

- Дума Чукотского автономного округа. Закон №33-ОЗ от 30 июня 1998 г. «Об административно-территориальном устройстве Чукотского автономного округа», в ред. Закона №55-ОЗ от 9 июня 2012 г. «О внесении изменений в Закон Чукотского автономного округа "Об административно-территориальном устройстве Чукотского автономного округа"». Вступил в силу по истечении десяти дней со дня его официального опубликования. Опубликован: "Ведомости", №7 (28), 14 мая 1999 г. (Duma of Chukotka Autonomous Okrug. Law #33-OZ of June 30, 1998 On the Administrative-Territorial Structure of Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, as amended by the Law #55-OZ of June 9, 2012 On Amending the Law of Chukotka Autonomous Okrug "On the Administrative-Territorial Structure of Chukotka Autonomous Okrug". Effective as of after ten days from the day of the official publication.).

- Правительство Чукотского автономного округа. Распоряжение №517-рп от 30 декабря 2008 г. «Об утверждении реестра административно-территориальных и территориальных образований Чукотского автономного округа», в ред. Распоряжения №323-рп от 27 июня 2011 г. «О внесении изменений в Распоряжение Правительства Чукотского автономного округа от 30 декабря 2008 года №517-рп». Опубликован: База данных "Консультант-плюс". (Government of Chukotka Autonomous Okrug. Directive #517-rp of December 30, 2008 On the Adoption of the Registry of the Administrative-Territorial and Territorial Formations of Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, as amended by the Directive #323-rp of June 27, 2011 On Amending the Government of Chukotka Autonomous Okrug Directive No. 517-rp of December 30, 2008. ).

- Дума Чукотского автономного округа. Закон №45-ОЗ от 29 ноября 2004 г. «О статусе, границах и административных центрах муниципальных образований на территории Провиденского района Чукотского автономного округа», в ред. Закона №89-ОЗ от 20 октября 2010 г «О преобразовании путём объединения поселений на территории Провиденского муниципального района и внесении изменений в Закон Чукотского автономного округа "О статусе, границах и административных центрах муниципальных образований на территории Провиденского района Чукотского автономного округа"». Вступил в силу через десять дней со дня официального опубликования. Опубликован: "Ведомости", №31/1 (178/1), 10 декабря 2004 г. (Duma of Chukotka Autonomous Okrug. Law #45-OZ of November 29, 2004 On the Status, Borders, and Administrative Centers of the Municipal Formations on the Territory of Providensky District of Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, as amended by the Law #89-OZ of October 20, 2010 On the Transformation via Merger of the Settlements on the Territory of Providensky Municipal District and on Amending the Law of Chukotka Autonomous Okrug "On the Status, Borders, and Administrative Centers of the Municipal Formations on the Territory of Providensky District of Chukotka Autonomous Okrug". Effective as of the day which is ten days after the official publication date.).

- Petit Futé: Chukotka, Strogoff, M, Brochet, P-C and Auzias, D. "Avant-Garde" Publishing House, 2006.

- Provideniya Museum Catalogue, various authors, translated by Bland, R.L., Shared Beringia Heritage Program, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. April 2002.