Prostitution in Laos

Prostitution in Laos is regarded as a criminal activity and can be subject to severe prosecution. It is much less common than in neighbouring Thailand.[1]:135 Soliciting for prostitution takes place mainly in the city's bars and clubs,[2] although street prostitution also takes place. The visibility of prostitution in Laos belies the practice's illegality.[3] UNAIDS estimates there to be 13,400 prostitutes in the country.[4]

Most prostitutes in Laos are from poor rural Laotian families and the country's ethnic minorities. In addition to these, there are many prostitutes in Laos from China and Vietnam,[5] while some Laotian women go to Thailand to work as sex workers.[6] Laos has been identified as a source country for women and girls trafficked for commercial sexual exploitation in Thailand.[7]

Many female sex workers in Laos are at high risk of sexually transmitted infection (STI) and disease. They often have limited access to treatment and services due to cultural sensitivity regarding sexuality and pre-marital sex.[8]

History

The establishment of the French Protectorate of Laos in 1893 resulted in the arrival of French civil servants who took "local wives" while posted in the country. Prostitution increased during the First Indochina War and the Vietnam War as a result of the presence of foreign troops in Laos. At this time prostitutes came from Thailand to work in the nightclubs and bars of the capital city Vientiane. During the 1960s and 1970s the country's involvement in the Vietnam War led to Vientiane becoming famous for its brothels and ping pong show bars.[6] As early as the 1950s, prostitution was discouraged by the Lao government as a social evil.[1]:154 When the Lao People's Democratic Republic was established in 1975, prostitution was criminalised.[5] Brothels were prohibited by law and disappeared from the country.[2] Prostitutes were initially interned in rehabilitation camps called don nang ("women's island"), though this practice was later discontinued.[3] In the 1990s, tourism and nightclubs returned to the country and with them prostitution became evident again.[5]

Causes

Poverty in Laos is a cause of increased prostitution in the country, with the sex industry in neighbouring Thailand attracting sex workers from Laos.[1]:134 Research published in 2012 indicated that sex workers considered the profession to be "an easy and good source of income compared to other jobs". They also said that it had the advantage of being "suitable for a low-educated person because working in a bar does not require formal training or skills and is quickly learned."[3]

Locations

Brothels are prohibited by Lao law.[2] Female sex workers in Laos are often employed as hostesses in places of entertainment, such as beer bars, "drinkshops", karaoke bars, nightclubs, guest houses and restaurants. They serve beer and snacks and provide conversation as well as selling sex. Pimps are sometimes used to find clients. Sexual services are provided in guest houses, hotels, or the client's room, which are usually attached to places of entertainment. Otherwise they tend to take place in remote areas.[3] The country's Golden Triangle Special Economic Zone in Bokeo Province has been called "a mecca of gambling, prostitution and illicit trade".[9]

The Khmu

By 2011, changing socio-economic conditions in rural Laos had resulted in Laotian women from the Khmu ethnic minority becoming predominant at the lower end of the Laotian sex industry.[10] The Khmu are a minority ethnic group that reside mostly in isolated and mountainous areas in the Upper Mekong region of Laos. They are the second largest ethnic group after the lowland Lao and make up more than 10 percent of the 6.2 million population.[11] There are a significant number of Khmu women in northern Laos that are involved in the commercial sex industry. Many of these women voluntarily leave their villages due to the very poor living conditions there. The Khmu women mostly move to border areas around the upper Mekong where there is more infrastructure, including bars, restaurants, and casinos. In addition, "Chinese sex workers at both casinos and local commercial sex venues increasingly host itinerant laborers and gamblers. Meanwhile, as a nod to promised development assistance, Chinese casino managers promote 'ethnic tourism' by supporting beauty contests in neighboring villages".[10]

Sexual health

Research conducted into female sex workers published in 2011 indicated that while 99 percent of them reported using condoms, 26 percent had had an abortion. Of those who had been pregnant in the last six months, 89.4 percent had had an abortion.[8] Abortions in Laos are not only illegal, but also are generally performed in unsafe conditions by untrained practitioners.[12] In 2016, only 42 percent of all births were attended by skilled health professionals.[13] In 2004, infection rates of chlamydia and gonorrhea were 33 and 18 percent.[12] The Lao government implemented a national strategic and action plan in 2005, aimed at expanding universal access to treatment, support, and care. The primary target groups included female sex workers, mobile populations, and drug users. However, the plan has not had much of an impact due to the quality of STI services being relatively limited in Laos.[12]

Cultural issues

Access to information and treatment regarding AIDS/HIV/STIs remains limited in Laos due to a conservative culture and sensitivity towards sexuality.[14] Many individuals reported a fear of going to health facilities for treatment due to social discrimination regarding pre-marital sex and "clinicians' negative attitudes towards 'dirty disease'".[15] A general lack of knowledge exists in Laos regarding RTI/STIs. The main sources of information are radio and television. However, access to health information is difficult in rural areas.[15] One study suggested that providers of contraceptive information and supplies are influenced by Lao norms, which disapprove of pre-marital sex, and stigmatize women who seek contraceptive services.[12]

HIV/AIDS

In 2004, between 0.8 percent and 4.2 percent of female sex workers in Laos were estimated to be infected with HIV/AIDS.[3] In 2015 the HIV prevalence for the total Laos population was 0.2 percent with 1096 new infections and 128 AIDS related deaths.[13] In 2016, an estimated 4,900 women aged 15 and up were living with HIV.[13]

Sex trafficking

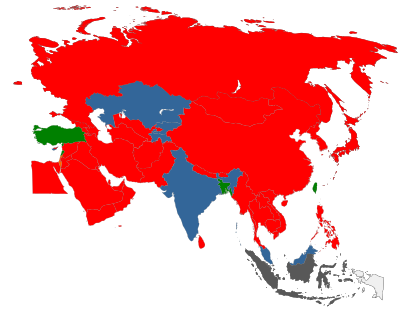

Laos is a source and, to a lesser extent, a transit and destination country for women and children subjected to sex trafficking. Lao trafficking victims, especially from the southern region of the country, are often migrants seeking opportunities abroad who then experience sexual exploitation in destination countries, most often Thailand, as well as Vietnam, Malaysia, China, Taiwan, and Japan. Some migrate with the assistance of brokers charging fees, while others move independently through Laos’ 23 official border crossings using valid travel documents. Traffickers take advantage of this migration, and the steady movement of Lao population through the country's 50 unofficial and infrequently-monitored border crossings, to facilitate the trafficking of Lao individuals in neighboring countries. Traffickers in rural communities often lure acquaintances and relatives with false promises of legitimate work opportunities in neighboring countries, then subject them to sex trafficking.[16]

A large number of victims, particularly women and girls, are exploited in Thailand's commercial sex industry. Some number of women and girls from Laos are sold as brides in China and subjected to sex trafficking. Some local officials reportedly contributed to trafficking vulnerabilities by accepting payments to facilitate the immigration of girls to China.[16]

Laos is reportedly a transit country for some Vietnamese and Chinese women and girls who are subjected to sex trafficking in neighboring countries, particularly Thailand. Chinese women and girls are also subjected to sex trafficking within Laos.[16]

The United States Department of State Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons ranks Laos as a 'Tier 3' country.[16]

References

- Kislenko, Arne (2009). Culture and Customs of Laos. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9780313339776.

- "Vientiane, Laos 2015 – City Nightlife, Clubs, Sex and Lao Family Life". www.retire-asia.com. Retire Asia. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- Phrasisombath, Ketkesone; Faxelid, Elisabeth; Sychareun, Vanphanom; Thomsen, Sarah (20 November 2012). "Risks, benefits and survival strategies – views from female sex workers in Savannakhet, Laos". BMC Public Health. 12: 1004. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-1004. PMC 3507866. PMID 23164407.

- "Sex workers: Population size estimate - Number, 2016". www.aidsinfoonline.org. UNAIDS. Archived from the original on 4 June 2019. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- Stuart-Fox, Martin (2008). Historical Dictionary of Laos. Scarecrow Press. p. 272. ISBN 9780810864115.

- Jeffrey Hays (2008). "Sex in Laos". Facts and Details. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- "Trafficking in Persons Report 2008: Laos". www.state.gov. U.S. Department of State. 4 June 2008. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- Morineau, Guy; Neilsen, Graham; Heng, Sopheab; Phimpachan, Chansy; Mustikawati, Dyah E (2011-08-01). "Falling through the cracks: contraceptive needs of female sex workers in Cambodia and Laos". Contraception. 84 (2): 194–198. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2010.11.003. ISSN 0010-7824. PMID 21757062.

- Jonathan Kaiman (8 September 2015). "In Laos' economic zone, a casino and illicit trade beckon in 'lawless playground'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 13 September 2015.

- Lyttleton, Chris; Vorabouth, Sisouvanh (24 March 2011). "Trade circles: aspirations and ethnicity in commercial sex in Laos". Culture, Health & Sexuality. 13 (sup2): S263–S277. doi:10.1080/13691058.2011.562307. PMID 21442500.

- de Sa, Joia; Bouttasing, Namthipkesone; Sampson, Louise; Perks, Carol; Osrin, David; Prost, Audrey (2012-04-20). "Identifying priorities to improve maternal and child nutrition among the Khmu ethnic group, Laos: a formative study". Maternal & Child Nutrition. 9 (4): 452–466. doi:10.1111/j.1740-8709.2012.00406.x. ISSN 1740-8695. PMC 3496764. PMID 22515273.

- Sychareun, Vanphanom (18 May 2004). "Meeting the Contraceptive Needs of Unmarried Young People: Attitudes of Formal and Informal Sector Providers in Vientiane Municipality, Lao PDR". Reproductive Health Matters. 12 (23): 155–165. doi:10.1016/s0968-8080(04)23117-2. ISSN 0968-8080.

- "Country profiles on HIV/AIDS". WHO Western Pacific Region. Retrieved 2017-10-28.

- Phrasisombath, Ketkesone; Thomsen, Sarah; Sychareun, Vanphanom; Faxelid, Elisabeth (2012-02-14). "Care seeking behaviour and barriers to accessing services for sexually transmitted infections among female sex workers in Laos: a cross-sectional study". BMC Health Services Research. 12 (1): 37. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-12-37. ISSN 1472-6963. PMC 3347996. PMID 22333560.

- Sihavong, Amphoy; Lundborg, Cecilia Stålsby; Syhakhang, Lamphone; Kounnavong, Sengchanh; Wahlström, Rolf; Freudenthal, Solveig (7 January 2011). "Community Perceptions and Treatment-Seeking Behaviour Regarding Reproductive Tract Infections Including Sexually Transmitted Infections in Lao PDR: A Qualitative Study". Journal of Biosocial Science. 43 (3): 285–303. doi:10.1017/S002193201000074X. ISSN 1469-7599. PMID 21211093.

- "Laos 2018 Trafficking in Persons Report". U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on 29 July 2018. Retrieved 29 July 2018.