Prosopagnosia

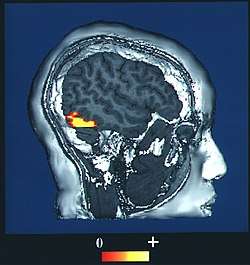

Prosopagnosia (from Greek prósōpon, meaning "face", and agnōsía, meaning "non-knowledge"), also called face blindness,[2] is a cognitive disorder of face perception in which the ability to recognize familiar faces, including one's own face (self-recognition), is impaired, while other aspects of visual processing (e.g., object discrimination) and intellectual functioning (e.g., decision-making) remain intact. The term originally referred to a condition following acute brain damage (acquired prosopagnosia), but a congenital or developmental form of the disorder also exists, with a prevalence rate of 2.5%.[3] The specific brain area usually associated with prosopagnosia is the fusiform gyrus,[4] which activates specifically in response to faces. The functionality of the fusiform gyrus allows most people to recognize faces in more detail than they do similarly complex inanimate objects. For those with prosopagnosia, the new method for recognizing faces depends on the less sensitive object-recognition system. The right hemisphere fusiform gyrus is more often involved in familiar face recognition than the left. It remains unclear whether the fusiform gyrus is only specific for the recognition of human faces or if it is also involved in highly trained visual stimuli.

| Prosopagnosia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Face blindness |

| |

| The fusiform face area, the part of the brain associated with facial recognition | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Neurology |

Acquired prosopagnosia results from occipito-temporal lobe damage and is most often found in adults. This is further subdivided into apperceptive and associative prosopagnosia. In congenital prosopagnosia, the individual never adequately develops the ability to recognize faces.[5]

Though there have been several attempts at remediation, no therapies have demonstrated lasting real-world improvements across a group of prosopagnosics. Prosopagnosics often learn to use "piecemeal" or "feature-by-feature" recognition strategies. This may involve secondary clues such as clothing, gait, hair color, skin color, body shape, and voice. Because the face seems to function as an important identifying feature in memory, it can also be difficult for people with this condition to keep track of information about people, and socialize normally with others. Prosopagnosia has also been associated with other disorders that are associated with nearby brain areas: left hemianopsia (loss of vision from left side of space, associated with damage to the right occipital lobe), achromatopsia (a deficit in color perception often associated with unilateral or bilateral lesions in the temporo-occipital junction) and topographical disorientation (a loss of environmental familiarity and difficulties in using landmarks, associated with lesions in the posterior part of the parahippocampal gyrus and anterior part of the lingual gyrus of the right hemisphere).[6] It is from the Greek: prosopon = "face" and agnosia = "not knowing".

The opposite of prosopagnosia is the skill of superior face recognition ability. People with this ability are called "super recognizers".[7]

Types

Apperceptive

Apperceptive prosopagnosia has typically been used to describe cases of acquired prosopagnosia with some of the earliest processes in the face perception system. The brain areas thought to play a critical role in apperceptive prosopagnosia are right occipital temporal regions.[8] People with this disorder cannot make any sense of faces and are unable to make same–different judgments when they are presented with pictures of different faces. They are unable to recognize both familiar and unfamiliar faces. In addition, apperceptive sub-types of prosopagnosia struggle recognizing facial emotion.[9] However, they may be able to recognize people based on non-face clues such as their clothing, hairstyle, skin color, or voice.[10] Apperceptive prosopagnosia is believed to be associated with impaired fusiform gyrus.[11] It is interesting that experiments on the formation of new face detectors in adults on face-like stimuli (learning to distinguish the faces of cats) indicate that such new detectors are formed not in the fusiform, but in the lingual gyrus.[12]

Associative

Associative prosopagnosia has typically been used to describe cases of acquired prosopagnosia with spared perceptual processes but impaired links between early face perception processes and the semantic information we hold about people in our memories. Right anterior temporal regions may also play a critical role in associative prosopagnosia.[8] People with this form of the disorder may be able to tell whether photos of people's faces are the same or different and derive the age and sex from a face (suggesting they can make sense of some face information) but may not be able to subsequently identify the person or provide any information about them such as their name, occupation, or when they were last encountered.[8] Associative prosopagnosia is thought to be due to impaired functioning of the parahippocampal gyrus.[13][14]

Developmental

Developmental prosopagnosia (DP), also called congenital prosopagnosia (CP), is a face-recognition deficit that is lifelong, manifesting in early childhood, and that cannot be attributed to acquired brain damage. A number of studies have found functional deficits in DP both on the basis of EEG measures and fMRI. It has been suggested that a genetic factor is responsible for the condition. The term "hereditary prosopagnosia" was introduced if DP affected more than one family member, essentially accenting the possible genetic contribution of this condition. To examine this possible genetic factor, 689 randomly selected students were administered a survey in which seventeen developmental prosopagnosics were quantifiably identified. Family members of fourteen of the DP individuals were interviewed to determine prosopagnosia-like characteristics, and in all fourteen families, at least one other affected family member was found.[15]

In 2005, a study led by Ingo Kennerknecht showed support for the proposed congenital disorder form of prosopagnosia. This study provides epidemiological evidence that congenital prosopagnosia is a frequently occurring cognitive disorder that often runs in families. The analysis of pedigree trees formed within the study also indicates that the segregation pattern of hereditary prosopagnosia (HPA) is fully compatible with autosomal dominant inheritance. This mode of inheritance explains why HPA is so common among certain families (Kennerknecht et al. 2006).[16]

Cause

Prosopagnosia can be caused by lesions in various parts of the inferior occipital areas (occipital face area), fusiform gyrus (fusiform face area), and the anterior temporal cortex.[8] Positron emission tomography (PET) and fMRI scans have shown that, in individuals without prosopagnosia, these areas are activated specifically in response to face stimuli.[6] The inferior occipital areas are mainly involved in the early stages of face perception and the anterior temporal structures integrate specific information about the face, voice, and name of a familiar person.[8]

Acquired prosopagnosia can develop as the result of several neurologically damaging causes. Vascular causes of prosopagnosia include posterior cerebral artery infarcts (PCAIs) and hemorrhages in the infero-medial part of the temporo-occipital area. These can be either bilateral or unilateral, but if they are unilateral, they are almost always in the right hemisphere.[6] Recent studies have confirmed that right hemisphere damage to the specific temporo-occipital areas mentioned above is sufficient to induce prosopagnosia. MRI scans of patients with prosopagnosia showed lesions isolated to the right hemisphere, while fMRI scans showed that the left hemisphere was functioning normally.[6] Unilateral left temporo-occipital lesions result in object agnosia, but spare face recognition processes, although a few cases have been documented where left unilateral damage resulted in prosopagnosia. It has been suggested that these face recognition impairments caused by left hemisphere damage are due to a semantic defect blocking retrieval processes that are involved in obtaining person-specific semantic information from the visual modality.[8]

Other less common etiologies include carbon monoxide poisoning, temporal lobectomy, encephalitis, neoplasm, right temporal lobe atrophy, injury, Parkinson's disease, and Alzheimer's disease.[6]

Diagnosis

There are few neuropsychological assessments that can definitively diagnose prosopagnosia. One commonly used test is the famous faces tests, where individuals are asked to recognize the faces of famous persons. However, this test is difficult to standardize. The Benton Facial Recognition Test (BFRT) is another test used by neuropsychologists to assess face recognition skills. Individuals are presented with a target face above six test faces and are asked to identify which test face matches the target face. The images are cropped to eliminate hair and clothes, as many people with prosopagnosia use hair and clothing cues to recognize faces. Both male and female faces are used during the test. For the first six items only one test face matches the target face; during the next seven items, three of the test faces match the target faces and the poses are different. The reliability of the BFRT was questioned when a study conducted by Duchaine and Nakayama showed that the average score for 11 self-reported prosopagnosics was within the normal range.[17]

The test may be useful for identifying patients with apperceptive prosopagnosia, since this is mainly a matching test and they are unable to recognize both familiar and unfamiliar faces. They would be unable to pass the test. It would not be useful in diagnosing patients with associative prosopagnosia since they are able to match faces.

The Cambridge Face Memory Test (CFMT) was developed by Duchaine and Nakayama to better diagnose people with prosopagnosia. This test initially presents individuals with three images each of six different target faces. They are then presented with many three-image series, which contain one image of a target face and two distracters. Duchaine and Nakayama showed that the CFMT is more accurate and efficient than previous tests in diagnosing patients with prosopagnosia. Their study compared the two tests and 75% of patients were diagnosed by the CFMT, while only 25% of patients were diagnosed by the BFRT. However, similar to the BFRT, patients are being asked to essentially match unfamiliar faces, as they are seen only briefly at the start of the test. The test is not currently widely used and will need further testing before it can be considered reliable.[17]

The 20-item Prosopagnosia Index (PI20)[18][19][20] is a freely available and validated self-report questionnaire that can be used alongside computer-based face recognition tests to help identify individuals with prosopagnosia. It has been validated using objective measures of face perception ability including famous face recognition tests and the Cambridge Face Memory Test. Less than 1.5% of the general population score above 65 on the PI20 and less than 65% on the CFMT.[20]

Treatment

There are no widely accepted treatments.[21]

Prognosis

Management strategies for acquired prosopagnosia, such as a person who has difficulty recognizing people's faces after a stroke, generally have a low rate of success.[21] Acquired prosopagnosia sometimes spontaneously resolves on its own.[21]

History

Selective inabilities to recognize faces were documented as early as the 19th century, and included case studies by Hughlings Jackson and Charcot. However, it was not named until the term prosopagnosia was first used in 1947 by Joachim Bodamer, a German neurologist. He described three cases, including a 24-year-old man who suffered a bullet wound to the head and lost his ability to recognize his friends, family, and even his own face. However, he was able to recognize and identify them through other sensory modalities such as auditory, tactile, and even other visual stimuli patterns (such as gait and other physical mannerisms). Bodamer gave his paper the title Die Prosop-Agnosie, derived from Classical Greek πρόσωπον (prósōpon) meaning "face" and αγνωσία (agnōsía) meaning "non-knowledge". In October 1996, Bill Choisser began popularizing the term face blindness for this condition;[2] the earliest-known use of the term is in an 1899 medical paper.[22]

A case of a prosopagnosia is "Dr P." in Oliver Sacks' 1985 book The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, though this is more properly considered to be one of a more general visual agnosia. Although Dr P. could not recognize his wife from her face, he was able to recognize her by her voice. His recognition of pictures of his family and friends appeared to be based on highly specific features, such as his brother's square jaw and big teeth. Oliver Sacks himself suffered from prosopagnosia, but did not know it for much of his life.[23]

The study of prosopagnosia has been crucial in the development of theories of face perception. Because prosopagnosia is not a unitary disorder (i.e., different people may show different types and levels of impairment), it has been argued that face perception involves a number of stages, each of which can cause qualitative differences in impairment that different persons with prosopagnosia may exhibit.[24]

This sort of evidence has been crucial in supporting the theory that there may be a specific face perception system in the brain. Most researchers agree that the facial perception process is holistic rather than featural, as it is for perception of most objects. A holistic perception of the face does not involve any explicit representation of local features (i.e., eyes, nose, mouth, etc.), but rather considers the face as a whole.[8][25][26] Because the prototypical face has a specific spatial layout (eyes are always located above nose, and nose located above mouth), it is beneficial to use a holistic approach to recognize individual/specific faces from a group of similar layouts. This holistic processing of the face is exactly what is damaged in prosopagnosics.[8] They are able to recognize the specific spatial layout and characteristics of facial features, but they are unable to process them as one entire face. This is counterintuitive to many people, as not everyone believes faces are "special" or perceived in a different way from other objects in the rest of the world. Though evidence suggests that other visual objects are processed in a holistic manner (e.g., dogs in dog experts), the size of these effects are smaller and are less consistently demonstrated than with faces. In a study conducted by Diamond and Carey, they showed this to be true by performing tests on dog-show judges. They showed pictures of dogs to the judges and to a control group and they then inverted those same pictures and showed them again. The dog-show judges had greater difficulty in recognizing the dogs once inverted compared to the control group; the inversion effect, the increased difficulty in recognizing a picture once inverted, was shown to be in effect. It was previously believed that the inversion effect was associated only with faces, but this study shows that it may apply to any category of expertise.[27]

It has also been argued that prosopagnosia may be a general impairment in understanding how individual perceptual components make up the structure or gestalt of an object. Psychologist Martha Farah has been particularly associated with this view.[28][29]

Children

Developmental prosopagnosia can be a difficult thing for a child to both understand and cope with. Many adults with developmental prosopagnosia report that for a long time they had no idea that they had a deficit in face processing, unaware that others could distinguish people solely on facial differences.[30]

Prosopagnosia in children may be overlooked; they may just appear to be very shy or slightly odd due to their inability to recognize faces. They may also have a hard time making friends, as they may not recognize their classmates. They often make friends with children who have very clear, distinguishing features.

Children with prosopagnosia may also have difficulties following the plots of television shows and movies, as they have trouble recognizing the different characters. They tend to gravitate towards cartoons, in which characters have simple but well-defined characteristics, and tend to wear the same clothes, may be strikingly different colours or even different species. Prosopagnosiac children even have a hard time telling family members apart, or recognizing people out of context (e.g., the teacher in a grocery store).[31] Some have difficulty recognising themselves in group photographs.

Additionally, children with prosopagnosia can have a difficult time at school, as many school professionals are not well versed in prosopagnosia, if they are aware of the disorder at all.[32]

Notable people with prosopagnosia

- Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury (1830–1903)[33]

- Margaret Kerry (born 1929), American actress and reference model for Tinker Bell[34]

- Oliver Sacks (1933–2015), British neurologist[35]

- Jane Goodall (born 1934), English primatologist[36]

- Karl Kruszelnicki (born 1948), Australian science communicator[37]

- Chuck Close (born 1949), American painter[38]

- Duncan Bannatyne (born 1949), Scottish entrepreneur[39]

- Steve Wozniak (born 1950), American computer engineer and co-founder of Apple Inc.[40]

- John Hickenlooper (born 1952), former Governor of Colorado[41]

- Jim Woodring (born 1952), American cartoonist[42][43]

- Stephen Fry (born 1957), English actor[44][45]

- Mary Ann Sieghart (born 1961), English journalist and radio presenter[46]

- Markos Moulitsas (born 1971), American blogger and former member of the military[47]

- Victoria, Crown Princess of Sweden (born 1977)[48][49]

See also

- Alexithymia

- Amygdala

- Aphantasia

- Cognitive neuropsychology

- Covert facial recognition

- Face perception

- Faces in the Crowd (film)

- Fregoli delusion

- N170

- Mirrored-self misidentification

- Prosopamnesia

- Recognition of human individuals

- Super recognisers

- Temporal lobe epilepsy

- Thatcher effect

References

- prosopagnosia. collinsdictionary.com

- Davis, Joshua (November 2006). "Face Blind". Wired. Retrieved 31 December 2014. ("[Bill] Choisser had even begun to popularize a name for the condition: face blindness.")

- Grüter T, Grüter M, Carbon CC (2008). "Neural and genetic foundations of face recognition and prosopagnosia". J Neuropsychol. 2 (1): 79–97. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.571.9472. doi:10.1348/174866407X231001. PMID 19334306.

- "Face blindness not just skin deep". CNN. Retrieved 19 November 2015.

- Behrmann M, Avidan G (April 2005). "Congenital prosopagnosia: face-blind from birth". Trends Cogn. Sci. (Regul. Ed.). 9 (4): 180–7. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.379.4935. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2005.02.011. PMID 15808500. S2CID 12029388.

- Mayer, Eugene; Rossion, Bruno (2007). Olivier Godefroy; Julien Bogousslavsky (eds.). Prosopagnosia (PDF). The Behavioral and Cognitive Neurology of Stroke (1 ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 315–334. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511544880.017. ISBN 9780521842617. OCLC 468190971. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 July 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- Barry, Elen (5 September 2018). "From Mountain of CCTV Footage, Pay Dirt: 2 Russians Are Named in Spy Poisoning". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- Gainotti G, Marra C (2011). "Differential contribution of right and left temporo-occipital and anterior temporal lesions to face recognition disorders". Front Hum Neurosci. 5: 55. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2011.00055. PMC 3108284. PMID 21687793.

- Biotti, Federica; Cook, Richard (2016). "Impaired perception of facial emotion in developmental prosopagnosia" (PDF). Cortex. 81: 126–36. doi:10.1016/j.cortex.2016.04.008. PMID 27208814.

- Barton, Jason J.S.; Cherkasova, Mariya v.; Press, Daniel Z.; Intriligator, James M.; O'Connor, Margaret (2004). "Perception functions in Prosopagnosia". Perception. 33 (8): 939–56. doi:10.1068/p5243. PMID 15521693. S2CID 25242447.

- Kanwisher N, McDermott J, Chun MM (1 June 1997). "The fusiform face area: a module in human extrastriate cortex specialized for face perception". J. Neurosci. 17 (11): 4302–11. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-11-04302.1997. PMC 6573547. PMID 9151747.

- Kozlovskiy, Stanislav; Popova, Alla; Shirenova, Sophie; Kiselnikov, Andrey; Chernorizov, Alexander; Danilova, Nina (October 2016). "Formation of Face-Selective Detectors: ERP- And Dipole-Source Localization Study". International Journal of Psychophysiology. 108: 68. doi:10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2016.07.223.

- Kozlovskiy, S.A.; Vartanov, A.V.; Shirenova, S.D.; Neklyudova, A.K. (2017). "Brain mechanisms of the Tip-of-the-Tongue state:An electroencephalography-based source localization study". Psychology in Russia: State of the Art. 10 (3): 218–230. doi:10.11621/pir.2017.0315. ISSN 2074-6857.

- Kozlovskiy, SA; Shirenova, SD; Vartanov, AV; Kiselnikov, AA; Marakshina, JA (October 2016). "Retrieval from Long-Term Memory: Dipole Sources Localization Study". International Journal of Psychophysiology. 108: 98. doi:10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2016.07.300.

- Grueter M, Grueter T, Bell V, Horst J, Laskowski W, Sperling K, Halligan PW, Ellis HD, Kennerknecht I (2007). "Hereditary Prosopagnosia: The First Case Series" (PDF). Cortex. 43 (6): 734–749. doi:10.1016/S0010-9452(08)70502-1. PMID 17710825. S2CID 4477925.

- Kennerknecht, I.; Grueter, T.; Welling, B.; Wentzek, S.; Horst, J. R.; Edwards, S.; Grueter, M. (August 2006). "First report of prevalence of non-syndromic hereditary prosopagnosia (HPA)" (PDF). American Journal of Medical Genetics. 140A (15): 1617–1622. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.31343. PMID 16817175.

- Duchaine B, Nakayama K (2006). "The Cambridge Face Memory Test: results for neurologically intact individuals and an investigation of its validity using inverted face stimuli and prosopagnosic participants". Neuropsychologia. 44 (4): 576–85. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2005.07.001. PMID 16169565.

- Shah, Punit; Gaule, Anne; Sowden, Sophie; Bird, Geoffrey; Cook, Richard (24 June 2015). "The 20-item prosopagnosia index (PI20): a self-report instrument for identifying developmental prosopagnosia". Royal Society Open Science. 2 (6): 140343. Bibcode:2015RSOS....240343S. doi:10.1098/rsos.140343. PMC 4632531. PMID 26543567.

- Shah, Punit; Sowden, Sophie; Gaule, Anne; Catmur, Caroline; Bird, Geoffrey (1 November 2015). "The 20 item prosopagnosia index (PI20): relationship with the Glasgow face-matching test". Royal Society Open Science. 2 (11): 150305. Bibcode:2015RSOS....250305S. doi:10.1098/rsos.150305. ISSN 2054-5703. PMC 4680610. PMID 26715995.

- Gray, Katie; Bird, Geoffrey; Cook, Richard (1 March 2017). "Robust associations between the 20-item prosopagnosia index and the Cambridge Face Memory Test in the general population". Royal Society Open Science. 4 (3): 160923. Bibcode:2017RSOS....460923G. doi:10.1098/rsos.160923. PMC 5383837. PMID 28405380.

- DeGutis, Joseph M.; Chiu, Christopher; Grosso, Mallory E.; Cohan, Sarah (5 August 2014). "Face processing improvements in prosopagnosia: successes and failures over the last 50 years". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 8: 561. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2014.00561. ISSN 1662-5161. PMC 4122168. PMID 25140137.

- Inglis, David (May 1899). "Moral Imbecility". Transactions of the Michigan State Medical Society. 23: 377–387.

- Katz, Neil (26 August 2010). "Prosopagnosia: Oliver Sacks' Battle with "Face Blindness"". CBS News. Retrieved 3 February 2010.

- Young, Andrew W.; Newcombe, F.; de Hanncombe, E.H.F.; Small, M. (1998). Andrew W. Young (ed.). Dissociable deficits after brain injury. Face and Mind. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 181–208. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198524205.003.0006. ISBN 9780198524212. OCLC 38014705.

- Richler JJ, Cheung OS, Gauthier I (April 2011). "Holistic processing predicts face recognition". Psychol Sci. 22 (4): 464–71. doi:10.1177/0956797611401753. PMC 3077885. PMID 21393576.

- Richler JJ, Wong YK, Gauthier I (April 2011). "Perceptual Expertise as a Shift from Strategic Interference to Automatic Holistic Processing". Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 20 (2): 129–134. doi:10.1177/0963721411402472. PMC 3104280. PMID 21643512.

- Diamond, R.; Carey, S. (June 1986). "Why faces are and are not special: an effect of expertise". Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 115 (2): 107–117. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.115.2.107. PMID 2940312.

- Farah MJ, Wilson KD, Drain M, Tanaka JN (July 1998). "What is "special" about face perception?". Psychol Rev. 105 (3): 482–98. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.105.3.482. PMID 9697428.

- Farah, Martha J. (2004). Visual agnosia. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-56203-4. OCLC 474679492.

- Nancy L. Mindick (2010). Understanding Facial Recognition Difficulties in Children: Prosopagnosia Management Strategies for Parents and Professionals (JKP Essentials). Jessica Kingsley Pub. ISBN 978-1-84905-802-5. OCLC 610833680.

- Schmalzl L, Palermo R, Green M, Brunsdon R, Coltheart M (July 2008). "Training of familiar face recognition and visual scan paths for faces in a child with congenital prosopagnosia". Cogn Neuropsychol. 25 (5): 704–29. doi:10.1080/02643290802299350. PMID 18720102. S2CID 29278660.

- Wilson, C. Ellie; Palermo, Romina; Schmalzl, Laura; Brock, Jon (February 2010). "Specificity of impaired facial identity recognition in children with suspected developmental prosopagnosia". Cognitive Neuropsychology. 27 (1): 30–45. doi:10.1080/02643294.2010.490207. PMID 20623389. S2CID 35860566.

- Grüter, Thomas. "Prosopagnosia in biographies and autobiographies" (PDF). Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- Rembulat, Vince (2 July 2019). "THE 'REAL' TINKER BELL". Manteca Bulletin. Manteca, CA. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- Katz, Neil (26 August 2010). "Prosopagnosia: Oliver Sacks' Battle with "Face Blindness"". CBS News. Retrieved 3 February 2010.

- "Photos: The faces of those who don't recognize faces". CNN. 23 May 2013.

- "Dr Karl on what it's like to live with face blindness". abc.net.au. ABC. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

- "Mosaic Art NOW: Prosopagnosia: Portraitist Chuck Close". mosaicartnow.com. Archived from the original on 21 August 2017. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- Tobin, Lucy (20 June 2011). "Researchers explore problems of 'face blindness'". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- Kelion, Leo (9 September 2015). "Steve Wozniak: Shocked and amazed by Steve Jobs movie". BBC. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- "John Hickenlooper didn't mean to forget who you are: How face blindness has affected his political career". CNN. 26 June 2019.

- https://www.lambiek.net/artists/w/woodring.htm

- Jim Woodring speech Making Light VASD Program, around the 32:00 mark. 24 March 2016.

- Sieghart, Mary Ann (1 July 2016). "Who Are You Again?". BBC Radio 4.

- Hepworth, David (25 June 2016). "Who are you again? What it's like to never remember a face". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- Kelly Strange "Everyone looks the same to me", Mirror.co.uk website, 9 November 2007. Retrieved 15 April 2008.

- "Photos: The faces of those who don't recognize faces". CNN. 23 May 2013.

- "Princess Victoria's face confession".

- "The Art of Living Magazine - Art, Culture and Wealth Management". The Art of Living Magazine. Archived from the original on 14 May 2017. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

Further reading

- Bruce, V.; Young, A. (2000). In the Eye of the Beholder: The Science of Face Perception. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-852439-7.

- Duchaine, BC; Nakayama, K (April 2006). "Developmental prosopagnosia: a window to content-specific face processing". Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 16 (2): 166–73. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2006.03.003. PMID 16563738. S2CID 14102858.

- Farah, Martha J. (1990). Visual agnosia: disorders of object recognition and what they tell us about normal vision. Cambridge: M.I.T. Press. ISBN 978-0-262-06135-3. OCLC 750525204.

- Oliver Sacks (30 August 2010). "Prosopagnosia, the science behind face blindness". The New Yorker. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- Heather Sellers (2010). You Don't Look Like Anyone I Know. Riverhead Hardcover. ISBN 978-1-59448-773-6. OCLC 535490485.

- Lyall, Sarah (27 November 2017). "Face Blindness: Sarah Lyall on a curious condition". Five Dials. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- Dingfelder, Sadie (21 August 2019). "My life with face blindness: I spent decades unable to recognize people. Then I learned why". Washington Post. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

External links

| Look up prosopagnosia in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikiversity has learning resources about Prosopagnosia |

- Face Blind!—The online book on face blindness by Bill Choisser, San Francisco.

- Prosopagnosia Research Center at Dartmouth College, Harvard University and University College London.

- Prosopagnosia Research at Bournemouth University

| Classification |

|---|