Prosopis tamarugo

Prosopis tamarugo, commonly known as the tamarugo, is a species of flowering tree in the pea family, Fabaceae, subfamilia Mimosoideae. It is only found in northern Chile, particularly in the Pampa del Tamarugal, some 70 km (43 mi) east of the city of Iquique. This bushy tree apparently grows without the benefit of rainfall, and it is thought obtains some water from dew. Studies indicate it is a Phreatophyte ; having deep roots that tap into ground water supplies. It also participates in hydraulic redistribution moving water from deeper levels to the upper and also reversing the process in times of severe drought.[2]

| Prosopis tamarugo | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae |

| Clade: | Mimosoideae |

| Genus: | Prosopis |

| Species: | P. tamarugo |

| Binomial name | |

| Prosopis tamarugo Phil. | |

Scattered stands of the trees have been cut down for firewood. The trees grow on saline soils that do not allow for other trees. The species is a valuable source of charcoal and lumber and the leaves and fruits are also food for goats. It has been planted in Spain.[3]

Physiology and biology

Prosopis tamarugo is a very drought and salt tolerant tree. Belonging to the family of legumes, the tree has the potential to fix nitrogen through rhizobial symbiosis with bacteria. On nutrient-poor soils the tree can therefore compete better compared to other non-nitrogen fixing plants. Prosopis tamarugo has the ability to grow very deep roots, leading to extreme drought tolerance. The plant has been observed to root down to groundwater tables at 20 m depth, allowing it to survive drought periods enduring several months.[4] Furthermore, the tree is able to absorb moisture from atmosphere and redirect it to the rhizosphere, where water is exudated to the surrounding soil in a kind of reversion of a normal guttation process.[5]

Salt tolerance

The genus Prosopis of the family Fabaceae is very well known to tolerate high saline soils without major restrictions in growth. The tree's salt tolerance probably evolved responding to salty conditions at its geographical place of origin.[6] In the northern Chilean Atacama desert, thick salt crusts which were formed in the past through desiccation of lakes are found widely. The tree can grow under saline crusts of 0.10–0.40 m thickness.[5] Tolerating high saline water, the tree potentially can be irrigated with seawater in coastal regions.[6]

Less saline water concentrations tend to have a promoting effect on growth. Although the tree shows quite a high saline tolerance, an excessive salt concentration in water leads to a decrease in growth, but growth is not stopped. With high saline concentration in water the root diameter decreases due to a reduction of the cortex layers of the roots.[7] Seedlings irrigated with high saline water concentration tend to have a decreased protein and carbohydrate content and a lower amount of photosynthetic pigments but a greater lipid content and oxygen uptake.

Agricultural use

History

In the 19th century, the natural forests of Tamarugo at Pampa del Tamarugal were intensively cut and used as source of firewood, so that they became almost extinct. Between 1960 and 1980 around 20,000 hectares (49,000 acres) in the Pampa del Tamarugal were revitalised with Tamarugo.[8]

Cultivation

The tree easy propagates and can be established from seedlings. It can grow in thick salt layers on clayey or sandy soils. Although it can absorb water from the atmosphere through its foliar system, initial costs can be reduced when tamarugo is planted where groundwater can be found between 2–10 m.

The seeds used for propagation come from selected trees. Seeds receive water every 2–3 days initially, later when the plant has established only once every 15 days. The small plants stay in a nursery for 3–5 months until a height of 8–10 cm. The plants are planted in a distance of 10 m from each other at a depth of 40–60 cm whereby the saline crust is broken to facilitate establishment. At the beginning, watering is needed for the establishment of the plants.[9]

Pests and diseases

Four insects are the main enemies of tamarugo:[10]

- "Palomilla violeta" (Leptotes trigemmatus) damages the fruits, leaves, flowers, and twigs

- "Polilla del fruto" (Cryptophlebia carpophagoides) damages the fruit and seeds

- "Polilla de la flor" (Ithome sp.) damages the flower

- "Bruco del tamarugo" (Scutobruchos gastoi) damages the seed

Controlling the pests with synthetic pesticides (pyrethoids) seems to be useful.[10]

Fodder use

At Pampa del Tamarugal, a silvopastoral system with small ruminants was established. The mature fruit and dry leaves of tamarugo fall on the soil and can be used as fodder for goats, sheep and cows.[11] Thanks to the leaves and the fruits of tamarugo, around 7000–9000 sheep and goats can survive in an original desert region. In fact, a 14–22 years old tree can produce 20–70 kg of fodder per year.[8] With trees aged 7 to 10 years, the estimated carrying capacity (sheep/ha) is about 0.5. Tamarugo is unused until an age of 6 years. For this reason the trees should be grown only in areas bigger than 500 ha to cover the development costs.[12] Although Tamarugo shows a high quantity of fruit fiber the forage quality is poor because of the low digestible energy content compared to cereal stalks. The goats are more efficient in digesting rougher forage and consume about 3.46 kg of fruits and foliage per day whereas sheep eat only 1.88 kg per day. Even if the existence of Tamarugo allows the livestock production in the Pampa del Tamarugal, supplemental feeding is needed. Locally available fodder are wheat bran and alfalfa hay.[10]

Besides fodder and fuelwood, tamarugo plantations provide shelter to wildlife and recreational opportunities. In contrast to the deserted land, tamarugo plantations also provide vegetation cover.[8]

References

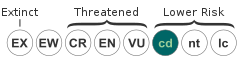

- González, M. (1998). "Prosopis tamarugo". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1998: e.T32037A9676582. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.1998.RLTS.T32037A9676582.en. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- Mooney, HA; Sl Gulmon; PW Rundel; J Ehleringer (1980). "Further observations on the water relations of Prosopis tamarugo of the northern Atacama desert". Oecologia. 44 (2): 177–180. Bibcode:1980Oecol..44..177M. doi:10.1007/bf00572676. JSTOR 4216007. PMID 28310553.

- "Chilean plants cultivated in Spain" (PDF). José Manuel Sánchez de Lorenzo-Cáceres. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-20. Retrieved 2010-07-16.

- Calderon, Gabriela; Garrido, Marco; Acevedo, Edmundo (2015-12-02). "Prosopis tamarugo Phil.: a native tree from the Atacama Desert groundwater table depth thresholds for conservation". Revista Chilena de Historia Natural. 88: 18. doi:10.1186/s40693-015-0048-0. ISSN 0717-6317.

- "The Current State of Knowledge on Prosopis tamarugo". www.fao.org. Retrieved 2017-11-16.

- Felker, Peter; Clark, Peter R.; Laag, A. E.; Pratt, P. F. (1981-10-01). "Salinity tolerance of the tree legumes: Mesquite (Prosopis glandulosa var.torreyana, P. velutina andP. articulata) Algarrobo (P. chilensis), Kiawe (P. pallida) and Tamarugo (P. tamarugo) grown in sand culture on nitrogen-free media". Plant and Soil. 61 (3): 311–317. doi:10.1007/BF02182012. ISSN 0032-079X.

- VALENTI, G. SERRATO; FERRO, M.; FERRARO, D.; RIVEROS, F. (1991-07-01). "Anatomical Changes in Prosopis tamarugo Phil. Seedlings Growing at Different Levels of NaCl Salinity". Annals of Botany. 68 (1): 47–53. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aob.a088217. ISSN 0305-7364.

- Ormazábal, C. S. (1991-06-01). "Silvopastoral systems in arid and semiarid zones of northern Chile". Agroforestry Systems. 14 (3): 207–217. doi:10.1007/BF00115736. ISSN 0167-4366.

- Alonso, Jaime Latorre (1990-12-01). "Reforestation of arid and semi-arid zones in Chile". Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment. Proceedings of a Workshop on Degradation of Arid Zones in the Mediterranean Region Plant Growth. 33 (2): 111–127. doi:10.1016/0167-8809(90)90237-8.

- Luis, Zelada G. (1986-10-01). "The influence of the productivity of Prosopis tamarugo on livestock production in the Pampa del Tamarugal — a review". Forest Ecology and Management. Establishment and Productivity of Tree Plantings in Semiarid Regions. 16 (1): 15–31. doi:10.1016/0378-1127(86)90004-6.

- Pak, Nelly; Araya, Hector; Villalón, Raymona; Tagle, Maria A. (1977-01-01). "Analytical study of tamarugo (prosopis tamarugo) an autochthonous chilean feed". Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 28 (1): 59–62. doi:10.1002/jsfa.2740280109. ISSN 1097-0010.

- Riveros, F. "The genus Prosopis and its potential to improve livestock production in arid and semi-arid regions" (PDF). FAO - Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved 2017-11-18.

- "Prosopis tamarugo". Ornamental trees in Spain (in Spanish). Retrieved 2010-03-30.