Prosecution of Syrian civil war criminals

Prosecution of Syrian civil war criminals, who were the participants of perpetrated crimes [recorded 1] of extermination, murder, rape or other forms of sexual violence, torture and imprisonment either (1) in the context of widespread and systematic detentions by Syrian government or (2) by groups established and operated under the territory of Syria before end of conflict is central to peace as "accountability for serious violations of international humanitarian law and human rights is central to achieving and maintaining durable peace in Syria, stated UN Under-Secretary-General Rosemary DiCarlo"[2] Groups operated under the Syrian territory includes the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) and Hayat Tahrir al-Sham.

| |

|---|---|

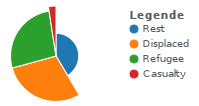

| Population 21 ±.5: Displaced 6 ±.5, Refugee 5.5 ±.5, Casualty 0.5 ±.1 (millions) | |

| Syrian refugees | |

| By country | Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan, Egypt |

| Settlements | Camps: (Jordan) |

| Displaced Syrians | |

| De-escalation | Safe zone |

| Casualties of the war | |

| Crimes | Human rights violations, Massacres, Rape |

| Return of refugees · Refugees as weapons · Prosecution of war criminals | |

The first war crimes trial related to the atrocities committed in Syria, concluded on 12 July 2016 in Germany, was the case of Aria L.[lower-alpha 1] performed under the Völkerstrafgesetzbuch (Code of Crimes against International Law (CCAIL)).[3]

Background

According to three international lawyers,[4] Syrian government officials were expected to risk facing war crimes charges in the light of a huge cache of evidence smuggled out of the country showing the "systematic killing" of about 11,000 detainees, constituting the 2014 Syrian detainee report. Most of the victims were young men and many corpses were emaciated, bloodstained and bore signs of torture. Some had no eyes; others showed signs of strangulation or electrocution.[5] Experts said this evidence was more detailed and on a far larger scale than anything else that had emerged from the then 34-month crisis.[6]

The United Nations (UN) summarised the human rights situation by stating that "siege warfare is employed in a context of egregious human rights and international humanitarian law violations. The warring parties do not fear being held accountable for their acts." Armed forces of both sides of the conflict blocked access of humanitarian convoys, confiscated food, cut off water supplies and targeted farmers working their fields. The report pointed to four places besieged by the government forces: Muadamiyah, Daraya, Yarmouk camp and Old City of Homs, as well as two areas under siege of rebel groups: Aleppo and Hama.[7][8] In Yarmouk Camp 20,000 residents are facing death by starvation due to blockade by the Syrian government forces and fighting between the army and Jabhat al-Nusra, which prevents food distribution by UNRWA.[7][9] In July 2015, the UN quietly removed Yarmouk from its list of besieged areas in Syria, despite not having been able deliver aid there for four months, and declined to explain why it had done so.[10]

ISIS forces have been accused by the UN of using public executions, amputations, and lashings in a campaign to instill fear. "Forces of the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham have committed torture, murder, acts tantamount to enforced disappearance and forced displacement as part of attacks on the civilian population in Aleppo and Raqqa governorates, amounting to crimes against humanity", said the report from 27 August 2014.[11]

Enforced disappearances and arbitrary detentions have also been a feature since the Syrian uprising began.[12] An Amnesty International report, published in November 2015, accused the Syrian government of forcibly disappearing more than 65,000 people since the beginning of the Syrian Civil War.[13] According to a report in May 2016 by the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, at least 60,000 people have been killed since March 2011 through torture or from poor humanitarian conditions in Syrian government prisons.[14]

In February 2017, Amnesty International published a report which accused the Syrian government of murdering an estimated 13,000 persons, mostly civilians, at the Saydnaya military prison. They said the killings began in 2011 and were still ongoing. Amnesty International described this as a "policy of deliberate extermination" and also stated that "These practices, which amount to war crimes and crimes against humanity, are authorised at the highest levels of the Syrian government."[15] Three months later, the United States State Department stated a crematorium had been identified near the prison. According to the U.S., it was being used to burn thousands of bodies of those killed by the government's forces and to cover up evidence of atrocities and war crimes.[16] Amnesty International expressed surprise at the claims about the crematorium, as the photographs used by the US are from 2013 and they did not see them as conclusive, and fugitive government officials have stated that the government buries those its executes in cemeteries on military grounds in Damascus.[17] The Syrian government denied the allegations.

Perpetrators

Four key security agencies have overseen government repression in Syria: the General Security Directorate, the Political Security Branch, the Military Intelligence Branch, and the Air Force Intelligence Branch. All three corps of the Syrian army have been deployed in a supporting role to the security forces; the civilian police have been involved in crowd control. The shabiha, led by the security forces, also participated in abuses.[18]:8–10 Since Hafez al-Assad's rule, individuals from the Alawite minority have controlled (although they not always formally headed) these four agencies, as well as several elite military units,[19]:72–3 and comprise the bulk of them.[20]

Groups operated under the Syrian territory includes the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) and Hayat Tahrir al-Sham.

Syrian Legal framework

Four of the international instruments ratified by Syria and which apply to events in the civil war are particularly relevant: the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR); the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights; the Convention on the Rights of the Child; and the UN Convention Against Torture. Syria is not a party to the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance, although it is bound by the provisions of the ICCPR that also prohibit enforced disappearances.[18]:5

International (International law) - National courts (Universal jurisdiction)?

All governments manage their territories with national laws. Prosecution for war crimes under the national laws of a given country [Germany, Netherlands ...] would typically depend on either the accused, the victim's residence or the occurrence of the event being in that country. Universal jurisdiction bypasses this constraint. In this mechanism, the "cases" that have no connection to the territory [e.g. crimes in high seas] have been used by prosecutors and have been criticized by human rights organisations as leading to a de facto presence requirement [e.g. existence of a crime can not be solved through collecting unbiased evidence from the crime scene, as the court don't have untethered access].

There are many perpetrators residing in Syria [the occurrence, the accused (is a Syrian national), the victim (is a Syrian national)]. International crimes are typically state crimes.[lower-alpha 2][21] If [since] a state is connected to a crime (directly or indirectly), most of the powerful perpetrators (state officials) reside in Syria. In such situations, the International Court of Justice is the judicial organ to settle international legal disputes submitted by states (UN) against other states.

International court

Richard Haass has argued that one way to encourage top-level defections is to "threaten war-crimes indictments by a certain date, say, August 15, for any senior official who remains a part of the government and is associated with its campaign against the Syrian people. Naming these individuals would concentrate minds in Damascus."[22]

Nevertheless, it remains unlikely in the short term, and some would argue this is a blessing in disguise, since this precludes the ICC's involvement while the conflict is still raging, a development that would arguably only increase the Assad government's violent obstinacy. The "United States cannot halt or reverse the militarization of the Syrian uprising, and should not try. What the United States can usefully do is manage this militarization by working with other governments, especially Syria’s neighbors in the region, to try to shape the activities of armed elements on the ground in a manner that will most effectively increase pressure on the regime".[23]

On 22 December 2016, with 105 votes in favour and 15 against, with 52 abstentions, the United Nations General Assembly has voted to establish an "independent panel to assist in the investigation and prosecution of those responsible for war crimes or crimes against humanity in Syria".[24]

Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Syria

The U.N. General Assembly created a new entity, the International, Impartial and Independent Mechanism, to build investigative files for future prosecutions, Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Syria (COI).[25]

On Wednesday, 7 August 2019, the UN Security Council was briefed on the recent findings [war crimes] by the COI.[2]

International Criminal Court

The U.N. Security Council has refused to address the crimes in Syria through ICC.

United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Navi Pillay and others have called for Syria to be referred to the International Criminal Court; however, it would be difficult for this to take place with within the foreseeable future because Syria is not a party to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, meaning the ICC has no jurisdiction there.

Referral could alternatively happen via the Security Council, but Russia and China would block.[26] Marc Lynch, who is in favour of a referral, noted a couple of other routes to the ICC were possible, and that overcoming Chinese and Russian opposition was not impossible.[27]

Special Tasked Court

Outside of the ICC, "some believe it would be possible to set up an ad hoc tribunal with a mandate to prosecute atrocities in Syria and Iraq. Such a tribunal would likely come in the form of a hybrid court and include a mix of domestic and international prosecutors and judges. Numerous observers, primarily American scholars and lawmakers, have pushed the establishment of such an institution, going so far as to draft a 'blueprint' for institution's statute. As with an ICC referral, their efforts have been unsuccessful to date."[28] Mark Kersten of the Munk School of Global Affairs at the University of Toronto, however, notes that it would be an "unprecedented challenge" to "prosecute all sides in the war that have committed war crimes" while at the same time retaining "the support of the major actors in the Syrian civil war, many of whom are implicated and would be prosecuted, for those war crimes."[28]

National courts

The European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR) is using both its own employees and other volunteers (Syrian lawyers working in EU member states) to gather evidence and establish cases.[29]

Netherlands

Netherlands is using concept of universal jurisdiction (Dutch version) laws to prosecute their cases.

On 2 September 2019, Ahmad al Khedr, also known as Abu Khuder, faced charges of murder and membership of a terrorist group.[30]

Germany

Germany has legally enacted universal jurisdiction (used on pirates and slave traders) to allow prosecutions for war crimes committed anywhere, against any people of any citizenship. German authorities started conduct a background inquiry to gather information in 2011. The aim (Strukturverfahren) was to establish war crimes cases, whether in Germany or in courts elsewhere (such as the International Criminal Court).[29] The investigative/protective units are organised under the federal prosecutor's office with 11 staff members, and 17 war-crimes police officers.[29] The police war-crimes unit established a total of 17 cases from 2011 to 2013 and 2,590 from 2014 to 2016.[29]

Under the Völkerstrafgesetzbuch (Code of Crimes against International Law (CCAIL)), the first German war crimes trial related to atrocities committed in the Syrian Civil War was the case of Aria L., a German who had been involved in Islamist and Salafist groups in Germany since 2013 and had travelled to Idlib in Syria in 2014. Aria L. was photographed in three separate photos in front of severed heads of Syrian army members mounted on metal spears. He was convicted of the war crime of treating protected persons in a gravely humiliating or degrading manner and sentence to two years' imprisonment on 12 July 2016.[3]

German prosecutors charged two Syrians, Kamel T. and Azad R. in 2016[31] and Basel A. and Majed A. in 2018,[32] for joining Salafist militant group such as Ahrar al-Sham and Jabhat al-Nusra.

On 23 August 2019, a 33-year-old Syrian (name undisclosed) was charged in the western Germany city of Koblenz with committing war crimes.[33]

In late October 2019, two Syrians suspected of having been secret service officers, Anwar Raslan and Eyad al-Gharib, were arrested in Germany and charged with crimes against humanity. Anwar Raslan was charged with 59 counts of murder, and rape and sexual assault. Eyad al-Gharib was charged with aiding and abetting a crime against humanity. Part of the evidence was based on the photographs of the 2014 Syrian detainee report, taken by a former Syrian military police photographer, nicknamed Caesar for security reasons.[34][35]

In May 2020, a Syrian doctor, Hafiz A., from Homs was accused of beating and torturing rebel men by the federal prosecutor's office in Karlsruhe.[36] In June 2020, another Syrian doctor from Homs, Alaa Moussa, was arrested in Hesse on suspicion of crimes against humanity.[37][38]

Sweden

On 19 February 2019, nine torture survivors submitted a criminal complaint against Syrian officials.[39]

Notes

- A German national, who has been a committed member of the Islamist and Salafist groups, murdered members of Syrian military personal and in two of these cases produced his own picture with severed heads

- Indirectly: enabled by (state apparatus ignoring the perpetrator) or directly: perpetrated through the apparatus (black operations).

References

Notes

- reports include:[1]

Citations

- "UN must refer Syria war crimes to ICC: Amnesty". GlobalPost. Archived from the original on 16 August 2013. Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- Staff. "Atrocity Alert No. 167: Syria, Afghanistan and the Geneva Conventions - Syrian Arab Republic". ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on 6 September 2019. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- Kroker, Patrick. "Justice for Syria? Opportunities and Limitations of Universal Jurisdiction Trials in Germany". European Journal of International Law. Archived from the original on 30 October 2019.

- Sir Desmond de Silva QC, former chief prosecutor of the special court for Sierra Leone, Sir Geoffrey Nice QC, the former lead prosecutor of former Yugoslavian president Slobodan Milošević, and Professor David Crane, who indicted President Charles Taylor of Liberia at the Sierra Leone court

- "foreignaffairs.house.gov". Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- "EXCLUSIVE: Gruesome Syria photos may prove torture by Assad regime". CNN. 21 January 2014. Archived from the original on 22 January 2014. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- "Report of the independent international commission of inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic". 12 February 2014. Archived from the original on 21 May 2014. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- "UN decries use of sieges, starvation in Syrian military strategy | The New Age Online". The New Age. South Africa. 5 March 2014. Archived from the original on 13 July 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- "Yarmouk update: Nusra's apparent return complicates UNRWA's hopes for food program". 3 March 2014. Archived from the original on 6 March 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- Dyke, Joe (24 July 2015). "Yarmouk camp no longer besieged, UN rules". IRIN. Archived from the original on 27 July 2015. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- "Syria and Isis committing war crimes, says UN". The Guardian. 27 August 2014. Archived from the original on 28 August 2014. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

- "syrias disappeared". BBC News. 11 November 2014. Archived from the original on 11 November 2014. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- Loveluck, Louisa (5 November 2015). "Amnesty accuses Syrian regime of 'disappearing' tens of thousands". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 27 April 2016. Retrieved 30 June 2016.

- Monitor: 60,000 dead in Syria government jails Archived 22 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine Al Jazeera

- "Syria: 13,000 secretly hanged in Saydnaya military prison – shocking new report". Amnesty International. Archived from the original on 22 February 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- "US accuses Syria of killing thousands of prisoners and burning the dead bodies in large crematorium outside Damascus". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 19 December 2018. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

Harris, Gardiner (15 May 2017). "Syria Prison Crematory Is Hiding Mass Executions, U.S. Says". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 15 May 2017. Retrieved 15 May 2017. - Barnard, Gardiner Harris, Anne; Gladstone, Rick (15 May 2017). "Syrian Crematory Is Hiding Mass Killings of Prisoners, U.S. Says". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 15 May 2017. Retrieved 17 May 2017.

- Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for maggagistic Human Rights on the situation of human rights in the Syrian Arab Republic (PDF). UN Human Rights Council. 15 September 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 May 2012. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- Byman, Daniel L. (2005). "The Implications of Leadership Change in the Arab World". Political Science Quarterly. 120 (1): 59–83. doi:10.1002/j.1538-165x.2005.tb00538.x. JSTOR 20202473.

- Goldsmith, Leon (16 April 2012). "Alawites for Assad". ForeignAffairs.com. Archived from the original on 22 April 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- staff (8 June 2016). Universal Jurisdiction in Germany? The Congo War Crimes Trial: First Case under the Code of Crimes against International Law (PDF). Berlin: The European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights. p. 28.

- Haass, Richard N. (16 July 2012). "Into Syria without Arms". Project Syndicate. Archived from the original on 20 July 2012. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- Cofman Wittes, Tamara (19 April 2012). "Options for U.S. Policy in Syria". Testimony before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on 19 June 2013. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- "Syria: UN approves mechanism to lay groundwork for investigations into possible war crimes". UN News Centre. 22 December 2016. Archived from the original on 23 December 2016. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- Goldston, James A. (8 August 2019). "Don't Give Up on the ICC". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 5 September 2019. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- Peel, Michael; Steinglass, Matt (2 March 2012). "ICC powerless to investigate Syrian regime". FT.com. Archived from the original on 11 July 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- Lynch, Marc (4 March 2012). "Can the ICC take on Syria?". Abu Aardvark's Middle East Blog. FP.com. Archived from the original on 8 December 2014. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- Mark Kersten, Calls for prosecuting war crimes in Syria are growing. Is international justice possible? Archived 20 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Washington Post (14 October 2016).

- Schaer, Cathrin (31 July 2019). "Prosecuting Syrian War-Crimes Suspects From Berlin". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 1 August 2019. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- van den Berg, Stephanie (2 September 2019). "Syrian war crimes suspect appears in Dutch court". Reuters. Archived from the original on 6 September 2019. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- "German prosecutors charge two Syrians for Ahrar al-Sham membership". DW (in German). 18 November 2016.

- "Staatsschutzverfahren wegen des Verdachts der Unterstützung einer terroristischen Vereinigung in Syrien". Justiz (in German). 19 October 2018.

- Staff. "Germany: Syrian man who posed with severed head charged with war crimes | DW | 23.08.2019". Deutsche Welle (23 August 2019). Archived from the original on 6 September 2019. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- Oltermann, Philip (29 October 2019). "Germany charges two Syrians with crimes against humanity". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 30 October 2019. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- "Assad's intelligence officers tried in German court". Rozana Radio. 23 April 2020.

- "Generalbundesanwalt ermittelt gegen syrischen Arzt aus Hessen: "Nehmt ihn mit"". Der Spiegel (in German). 22 May 2020.

- "Festnahme eines mutmaßlichen Mitarbeiters des syrischen Militärischen Geheimdienstes wegen des dringenden Tatverdachts eines Verbrechens gegen die Menschlichkeit". Der Generalbundesanwalt beim Bundesgerichtshof (in German). 22 June 2020.

- "Germany Has Arrested Alaa Moussa Accused of Torture". reform4syria.org. 22 June 2020.

- Nebehay, Stephanie (8 March 2019). "U.N. investigators hot on trail of Syrian war criminals". Reuters.