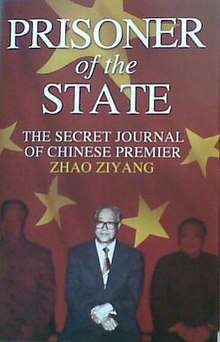

Prisoner of the State

Prisoner of the State: The Secret Journal of Premier Zhao Ziyang are the memoirs of the former General Secretary of the Communist Party of China, Zhao Ziyang, who was sacked after the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989. The book was published in English in May 2009,[1] to coincide with the twentieth anniversary of the clearing of the square by tanks on June 4, 1989. It is based on a series of about thirty audio tapes recorded secretly by Zhao while he was under house arrest in 1999 and 2000.[2]

| |

| Author | Zhao Ziyang |

|---|---|

| Original title | 改革歷程 |

| Translator | Bao Pu |

| Country | United States and United Kingdom |

| Language | Chinese, English |

| Genre | Non-fiction |

| Publisher | Simon & Schuster |

Publication date | May 19, 2009 |

| Media type | Print (Paperback) |

| Pages | 336 pp. (first edition, paperback) |

| ISBN | 978-1-4391-4938-6 (first edition for US, hardback); ISBN 978-1-84737-697-8 (first edition for UK, hardback) |

| OCLC | 301887109 |

| 951.058092 22 | |

| LC Class | DS779.29.Z467 A313 2009 |

Co-editor Adi Ignatius pinpoints a meeting held at Deng Xiaoping's home on May 17, 1989, less than three weeks before the suppression of the Tiananmen protests, as the key moment in the book. When Zhao argued that the government should look for ways to ease tensions with the protesters, two conservative officials immediately criticized him. Deng then announced he would impose martial law. Zhao commented: "I refused to become the General Secretary who mobilized the military to crack down on students."[3] In the last chapter, Zhao praises the Western system of parliamentary democracy and says that it is the only way China can solve its problems of corruption and a growing gap between the rich and poor.[4]

Key excerpts

Prior to publication, a number of newspapers and journals have published key extracts of Zhao's reflections on a range of topics:

On Tiananmen Square

- By insisting on my view of the student demonstrations and refusing to accept the decision to crack down with force, I knew what the consequences would be and what treatment I would receive... I knew that if I persistently upheld my view, I would ultimately be compelled to step down.

- On the night of June 3, while sitting in the courtyard with my family, I heard intense gunfire. A tragedy to shock the world had not been averted, and was happening after all.[5]

On democracy

- They (i.e. the democratic systems of socialist nations) are all just superficial. They are not systems in which the people are in charge, but rather are ruled by a few or even a single person.[6]

- In fact, it is the Western parliamentary democratic system that has demonstrated the most vitality. It seems that this system is currently the best one available.[7]

On Deng Xiaoping

- Deng had always stood out among the party elders as the one who emphasised the means of dictatorship. He often reminded people about its usefulness.[8]

On a new approach

- The reason I had such a deep interest in economic reform and devoted myself to finding ways to undertake this reform was that I was determined to eradicate the malady of China’s economic system at its roots. Without an understanding of the deficiencies of China’s economic system, I could not possibly have had such a strong urge for reform.[9]

Details of creation

Following the 1989 Tiananmen protests, Zhao was relieved of all positions in government and placed under house arrest. For the next sixteen years of his life, Zhao lived in forced seclusion in a quiet Beijing alley. Although minor details of his life leaked out, China scholars lamented that Zhao's account of events was to remain unknown. Zhao's production of the memoir, in complete secrecy, is the only surviving public record of the opinions and perspectives Zhao held later in his life.[10]

Zhao began secretly recording his autobiography on children's cassette tapes in 1999, and eventually completed approximately thirty tapes, each about six minutes in length. Zhao produced his audio journals by recording over inconspicuous low-quality tapes which were readily available in his home: children's music and Peking Opera. Zhao indicated the tapes' intended order by faint pencil markings, and no titles or notes on how Zhao intended the tapes to be otherwise interpreted or presented were ever recovered. The voices of several of Zhao's closest friends were heard in several of the later tapes, but were edited out of the published book in order to protect their identities. After the tapes' creation, Zhao smuggled them out of his residence by passing them to these friends. In order to minimize the risk that some tapes might be lost or confiscated, each participant was only entrusted with a small part of the total work.[10]

Because he could only produce the tapes during periods in which his guards were absent, the process of recording the tapes took over a year. Bao Pu, one of the editors who worked on publishing Zhao's memoir, first learned of the tapes' existence only after Zhao's death on January 17, 2005. It took several years for Bao to collect them and gain legal permission from Zhao's family to publish Zhao's autobiography.[11] Zhao's family has always maintained that they were completely unaware of the tapes' existence until contacted by Bao Pu. After Zhao's death a second set of tapes (perhaps the originals) were found in Zhao's home, and were returned to Zhao's family.[12]

Access in China

Adi Ignatius, one of the editors of the English-language edition, said that although the book was certain to be banned on the mainland, he believed some of its content would spread through the internet or bootleg editions.[13]

A Chinese edition of the book entitled Journey of the Reforms (改革歷程) was published by New Century Press and released in Hong Kong on May 29, days before the 20th anniversary of the Tiananmen crackdown on June 4.[14] New Century Press is run by Bao Pu, the son of Zhao Ziyang’s former aide, Bao Tong, who is under police surveillance in Beijing.[15] The first print-run of 14,000 copies was reported to have sold out in Hong Kong on its first day of release in several bookstore chains. Cheung Ka-wah of Greenfield Book Store, the Hong Kong distributor, commented "This book is the most sought-after that I've ever seen."[16]

Bibliographic reference (MLA)

- Zhao Ziyang. Prisoner of the State: The Secret Journal of Premier Zhao Ziyang. Trans & Ed. Bao Pu, Renee Chiang, and Adi Ignatius. New York: Simon and Schuster. 2009. ISBN 1-4391-4938-0.

References

- Bristow, Michael (May 14, 2009), "Secret Tiananmen memoirs revealed", BBC News, Beijing, retrieved July 6, 2009

- Link, Perry (May 17, 2009), "From the Inside, Out: Zhao Ziyang Continues His Fight Postmortem", Washington Post, retrieved July 6, 2009

- Ignatius, Adi (May 14, 2009), "The Secret Memoir of a Fallen Chinese Leader", Time Magazine, retrieved May 15, 2009

- Deposed Chinese leader's memoir out before June 4, Associated Press, May 14, 2009, retrieved July 6, 2009

- "Extract: "Prisoner of the State: The secret Journal of Zhao Ziyang"", The Daily Telegraph, May 14, 2009, retrieved July 6, 2009

- Zhao Ziyang's Testament. Far Eastern Economic Review, May 14, 2009. Retrieved May 15, 2009.

- The Insider Who Tried to Stop Tiananmen, Wall Street Journal, May 15, 2009. Retrieved May 15, 2009.

- Memoir describes failed attempt to avoid massacre. Irish Times, May 15, 2009. Retrieved May 15, 2009.

- Excerpts From Zhao Ziyang’s ‘Prisoner of the State’. New York Times, May 13, 2009. Retrieved May 17, 2009.

- Ignatius, Adi. "Preface". In Zhao Ziyang. Prisoner of the State: The Secret Journal of Premier Zhao Ziyang. Trans & Ed. Bao Pu, Renee Chiang, and Adi Ignatius. New York: Simon and Schuster. 2009. ISBN 1-4391-4938-0. p.x.

- Pomfret, John. "The Tiananmen Tapes: Zhao Ziyang's Memoir Criticizes Chinese Communist Party". The Washington Post. May 15, 2009. Retrieved September 20, 2011.

- Ignatius, Adi. "Preface". In Zhao Ziyang. Prisoner of the State: The Secret Journal of Premier Zhao Ziyang. Trans & Ed. Bao Pu, Renee Chiang, and Adi Ignatius. New York: Simon and Schuster. 2009. ISBN 1-4391-4938-0. p.x-xi.

- Secret Tiananmen Square Memoirs of Chinese Party Leader to be Published. The Guardian. May 14, 2009. Retrieved May 18, 2009.

- Zhao’s book: ‘We know the risks, we are prepared’. The Malaysian Insider, May 19, 2009. Archived June 1, 2009, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved May 19, 2009.

- Memoir describes failed attempt to avoid massacre. Irish Times, May 15, 2009. Retrieved May 18, 2009.

- Pomfret, James (May 2009). "Red-hot sales of Zhao's Chinese memoirs in Hong Kong". Reuters. Retrieved May 29, 2009.