Presumed Innocent (film)

Presumed Innocent is a 1990 American legal drama film based on the 1987 novel of the same name by Scott Turow. Directed by Alan J. Pakula, and written by Pakula and Frank Pierson, it stars Harrison Ford, Brian Dennehy, Raúl Juliá, Bonnie Bedelia, Paul Winfield and Greta Scacchi. The film follows Rusty Sabich (Ford), a prosecutor who is charged with the murder of his colleague and mistress Carolyn Polhemus (Scacchi).

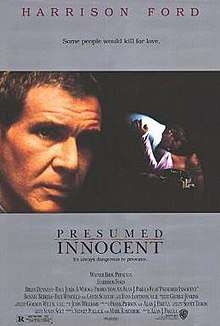

| Presumed Innocent | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Alan J. Pakula |

| Produced by | |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | Presumed Innocent by Scott Turow |

| Starring | |

| Music by | John Williams |

| Cinematography | Gordon Willis |

| Edited by | Evan A. Lottman |

Production company | Mirage Enterprises |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 127 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $20 million[1][2][3] |

| Box office | $221.3 million[4] |

Several studios and producers fought to secure the film rights one year before the novel was published. Producers Sydney Pollack and Mark Rosenberg acquired the rights in December 1986, and hired Pierson to write the script. After an unsuccessful pre-production development at United Artists, the project moved to Warner Bros., and Pakula was brought in to rewrite the script with Pierson before signing on as the film's director in January 1989. Principal photography commenced in July 1989 and concluded in October of that year, with a budget of $20 million. Filming took place on locations in Detroit, Windsor, Ontario, and New Jersey, and on soundstages at Kaufman Astoria Studios in New York.

Presumed Innocent premiered at the Fox Bruin Theater in Los Angeles, California on July 25, 1990, before being released in North America on July 27, 1990. The film has an approval rating of 86% at Rotten Tomatoes, with critics praising its directing, acting, and writing. It grossed $221 million worldwide, and became the eighth-highest-grossing film of 1990. The film was followed by a television miniseries, The Burden of Proof, in 1992, and a television film sequel, Innocent, in 2011.

Plot

Rozat "Rusty" Sabich is a prosecutor and the right-hand man of district attorney Raymond Horgan. When his colleague Carolyn Polhemus is found raped and murdered in her apartment, Raymond insists that Rusty take charge of the investigation. With the election for District Attorney approaching, Tommy Molto, the acting head of the homicide division, has left to join the rival campaign of Nico Della Guardia. Rusty, a married man, faces a conflict of interest since he had a brief sexual affair with Carolyn. As he had shown little ambition and would have therefore been of little use in advancing her career, Carolyn abruptly dumped him. Rusty has since reconciled with his wife Barbara, but is still obsessed with Carolyn.

Detective Harold Greer is initially in charge of the murder investigation, but Rusty has him replaced with his friend Detective Dan Lipranzer, whom he persuades to narrow the inquiry so that his relationship with Carolyn is left out. Rusty soon discovers that Molto is making his own inquiries. Aspects of the crime suggest that the killer knew police evidence-gathering procedures and covered up clues accordingly. Semen found in the victim's body contains only dead sperm. The killer's blood is type A, the same as Rusty's. When Della Guardia wins the election, he and Molto accuse Rusty of the murder and push to get evidence against him. Rusty's fingerprints are found on a beer glass from Carolyn's apartment, and fibers from his carpet at home match those found on her body. Lipranzer is removed from the case, and Greer's inquiries uncover the affair.

Raymond grows furious with Rusty's handling of the case, but admits that he had also been romantically involved with Carolyn at one time. Rusty calls on Sandy Stern, a top defense attorney. At trial, it is revealed that the beer glass is missing, and Stern persuades Judge Larren Lyttle to keep this from the jury. Raymond testifies and perjures himself, claiming that Rusty insisted on handling the investigation, thus confirming the defense's claim of a frame-up. Rusty discovers that Carolyn had acquired a file for a bribery case involving a man named Leon Wells. Upon being confronted by Rusty and Lipranzer, Wells confesses that he paid Judge Lyttle $1,500 to have criminal charges against him dropped, with Carolyn acting as a facilitator.

The thrust of Stern's defense is that Della Guardia and Molto have framed Rusty in order to cover up the bribery case. During the cross-examination of the coroner, it is revealed that Carolyn underwent a tubal ligation, thus having no reason to use the spermicidal contraceptive which was found on her. Stern asserts that the only explanation for this discrepancy is that the fluid sample was not actually taken from Carolyn's body. Based on the disappearance of the beer glass, the lack of motive and the fact that the fluid sample was rendered meaningless, Judge Lyttle dismisses the charges. Rusty confronts Stern for bringing up the bribery file in the case. Stern swears him to secrecy, revealing that Lyttle had a brief sexual encounter with Carolyn. Stern also confesses that he and Raymond knew that Lyttle was taking bribes, and although Lyttle had offered his resignation, Raymond felt that he was a brilliant judge and deserved another chance. Lipranzer meets with Rusty and reveals the missing beer glass, explaining that he never returned it to evidence when the investigation was turned over to Della Guardia and Molto. Rusty throws it into a river.

At his home, Rusty discovers a small hatchet covered with Carolyn's blood and hair on it. As he washes the tool, Barbara admits that she murdered Carolyn, her motive being Rusty's adulterous affair. She expresses that she had left enough evidence for Rusty to know that she committed the crime, but did not anticipate him being charged with the murder. In a voice-over, Rusty explains that Carolyn's murder has been written off as unsolved, since trying two people for the same crime is "a practical impossibility" and he cannot leave his son without a mother even if she could be tried. Rusty regrets that it was his own lust that caused his wife to commit murder.

Cast

- Harrison Ford as Rozat K. "Rusty" Sabich

- Brian Dennehy as Raymond Horgan

- Raul Julia as Alejandro "Sandy" Stern

- Bonnie Bedelia as Barbara Sabich

- Paul Winfield as Judge Larren L. Lyttle

- Greta Scacchi as Carolyn Polhemus

- John Spencer as Det. Dan Lipranzer

- Joe Grifasi as Tommy Molto

- Tom Mardirosian as Nico Della Guardia

- Anna Maria Horsford as Eugenia

- Sab Shimono as Dr. "Painless" Kumagai

- Bradley Whitford as Quentin "Jamie" Kemp

- Christine Estabrook as Lydia "Mac" MacDougall

- Michael Tolan as Mr. Polhemus

- Jesse Bradford as Nat Sabich

- Joseph Mazzello as Wendell McGaffen

- Tucker Smallwood as Det. Harold Greer

- David Wohl as Morrie Dickerman

- Jeffrey Wright as Prosecuting Attorney

Production

Development

Scott Turow's 1987 novel Presumed Innocent had first attracted film producers a year before it was published. The film rights were the subject of a bidding war among a host of established studios and producers.[2] David Brown and Richard D. Zanuck made the first bid of $75,000. Don Simpson and Jerry Bruckheimer initially offered $300,000, financed by Paramount Pictures, but backed down when bids climbed to $750,000. Peter Guber and Jon Peters,[2] and Sydney Pollack and Mark Rosenberg of Mirage Enterprises made $1 million bids of their own money.[2][5] Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and Irwin Winkler also made bids, while Universal Pictures passed on the project.[3] After Pollack and Rosenberg acquired the rights in December 1986,[6] United Artists negotiated with the producers to finance and distribute the film. In May 1987, Pollack hired Frank Pierson to write the script. Shortly after, United Artists backed out as a distributor. Roger Birnbaum, head of worldwide production for United Artists, claimed that the studio found the project "just too expensive".[2] In July 1988, the project moved to Warner Bros.[2]

Pollack and Rosenberg sent the script to Alan J. Pakula,[2][7] who felt that it needed improvement and spent a year rewriting it with Pierson.[8] Regarding the screenwriting process, Turow said, "There were three large narrative problems to solve. Point of view; getting around the first person narrative; time sequence; it's all flashback and Hollywood doesn't like that; and then just an awful lot of plot."[9] Pierson originally envisioned the film adaptation as being "a movie full of sex and blood".[8] Pakula felt that the concept of justice was more central to the story. He also wanted to present the film in a visual style that echoed the novel's narrative.[8] In making various changes from the novel, Pakula and Pierson added new dialogue and rewrote the ending.[2] Pakula signed on to direct the film in January 1989.[10]

Casting

Several established actors were considered for the leading role of Rusty Sabich. Kevin Costner turned down the role, and Robert Redford was vetoed by Pollack due to his age.[11][12] When he was hired to direct the film, Pakula only offered the role to Harrison Ford,[3] believing that the actor possessed an "Everyman quality" that best suited the character.[13] Ford's casting was confirmed in March 1989.[2] He received a $7 million salary for the role.[12] Turow was initially uncertain of Ford portraying Rusty but relented after seeing a few of the actor's films.[9] Ford said, "Friends warned me this was a tough role because Rusty is such a passive, interior character. Though Rusty's in every scene, all the action takes place around him. Things happen to him."[3] Upon being cast, Ford read the novel to avoid arguments over events and details that were left out in the book.[10] Ford also suggested to Pakula that Rusty have a buzz cut. He explained, "There are many things I found I could express with that short haircut. Simplest of all, I wanted to tell the audience to leave their baggage at home — not to expect the Harrison Ford they've seen before."[14]

In preparing for their roles, the actors were granted access to lawyers who would act as advisors.[15] Ford observed murder trials with Pakula at the Recorder's Court in Detroit and viewed training footage from the Michigan Prosecutors' Association.[10] Greta Scacchi, who plays Carolyn Polhemus, observed Linda Fairstein, head of the Manhattan District Attorney's sex crimes unit.[2][3] Raúl Juliá, who plays Sandy Stern, researched his role by meeting with criminal lawyer Michael Kennedy.[3][16] Paul Winfield lobbied for the role of Judge Larren Lyttle upon reading the novel and learning that the adaptation was to be directed by Pakula.[17] Winfield met with New York Supreme Court judge Bruce M. Wright, who insisted that he wear a judiciary robe and observe several cases.[10]

Filming

Pakula spent three weeks rehearsing with the actors before principal photography commenced on July 31, 1989[2][10] with a budget of $20 million.[1][2][3] Filming began in Detroit, where the production first filmed exterior scenes. Locations included the Renaissance Center's Westin Hotel, Philip A. Hart Plaza, the Woodbridge Tavern, Eastern Market, Jackie's Bar and Restaurant, St. Aubin Marina, and the International Plaza garage rooftop. On August 3, 1989, the production moved to Reaume Park in Windsor, Ontario for a 13-hour shoot.[18] After filming in Detroit ended on August 9, 1989, the production moved to Kaufman Astoria Studios in Queens, New York. The filmmakers constructed a courtroom modeled after one in Cleveland, Ohio that was unavailable for filming.[2][3] The production then moved to Newark. For two days, the North Reformed Church was used to depict the funeral of Carolyn Polhemus. From August 14 to August 15, the filmmakers shot scenes at Newark City Hall. The Essex County Courthouse was used for a brief courtroom sequence, and Newark's city morgue was used to depict the medical office of Dr. Kumagai. A housing project scheduled for demolition was used for a scene depicting Rusty and Detective Lipranzer's interrogation of a suspect.[18]

In late August, the crew relocated to Allendale, New Jersey. A suburban house on East Orchard Street was used to film exterior and interior scenes set in the Sabich family home. The house's cellar was used to film a scene involving Rusty and his wife.[19] The cast and crew then returned to Kaufman Astoria Studios to film the trial scenes.[2] Principal photography concluded on October 24, 1989.[20]

Release

Presumed Innocent held its world premiere at the Fox Bruin Theater in Los Angeles, California on July 25, 1990, with an afterparty held at Chasen's restaurant.[21] The film was released on July 27, 1990, distributed by Warner Bros.[2] A soundtrack album featuring the score by John Williams was released by the record label Varèse Sarabande on August 7, 1990.[22]

Box office

Released to a total of 1,349 theaters in the United States and Canada, the film grossed $11,718,981 on its first weekend, securing the number one position at the box office.[23] It saw a significant drop in attendance during its second weekend of release. The film earned an additional $10,176,663—a 13.2% overall decrease from the previous weekend—[23] and moved to second place behind Ghost.[24] In its third weekend, the film grossed an additional $7,901,866, for an overall domestic gross of $42,012,238. It grossed an additional $6,101,374 on its fourth weekend. The film returned to fourth place on its fifth week, grossing an additional $4,646,004, and returned to third place for the following two weeks.[23]

Presumed Innocent grossed $86,303,188 during its North American theatrical run. Coupled with its international take of $135 million, it accumulated $221,303,188 in worldwide box office totals.[4] In North America, it was the twelfth highest-grossing film of 1990,[25] and the fourth highest-grossing R-rated film released that year.[26] Worldwide, it was the eighth highest-grossing film of 1990,[27] as well as Warner Bros.' highest-grossing film that year.[28]

Reception

Critical response

The review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes gives the film an approval score of 87% based on 55 reviews, with an average rating of 7.43/10. The website's critical consensus reads, "Thanks to an outstanding script, focused direction by Alan Pakula, and a riveting performance from Harrison Ford, Presumed Innocent is the kind of effective courtroom thriller most others aspire to be."[32] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "A-" on an A+ to F scale.[33]

Warner Bros. requested in press releases that critics not discuss the film's ending.[2][3] Richard Schickel of Time magazine disregarded the request and revealed Rusty's innocence in his review. He wrote, "Carolyn's murderer has an excellent motive both for killing her... But it is hard to accept the possibility that the real perpetrator would leave his escape from the trap entirely to chance."[34] Jay Boyar of the Orlando Sentinel surmised, "It's not that Warner Bros. is actually concerned that reviewers will tip the solution to the murder mystery. It's that the studio wants to further the impression that the movie is full of surprises."[35] Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times stated, "Even if you think you know what the solution is, the performances are so clever and the screenplay ... is so subtle that it could well turn out that your expectations are wrong."[36]

Sheila Benson, writing for the Los Angeles Times, stated, "Intelligent, complex and enthralling, Presumed Innocent ... is one of those rare films where all the players seem to be in a state of grace, where the working of the machinery never shows and after it's over, one runs and reruns its intricacies with a profound sense of satisfaction."[37] Peter Travers, writing for Rolling Stone, called the film "a smart, passionate, steadily engrossing thriller".[38] Janet Maslin of The New York Times praised Pakula's direction, writing, "Pakula has directed an intense, enveloping, gratifyingly thorough screen adaptation of Mr. Turow's story."[39] Film critic Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote that film was "a top-notch courtroom drama that will keep you guessing if you haven't read the book; even if you have, it is still a very well crafted story."[40] Variety magazine praised the performances, writing, "Ford, in a very mature, subtle, lowkey performance, pulls off the difficult feat of making it impossible to be sure. Bedelia is wondrously controlled, and Scacchi, sans any hint of a European accent, is convincing and seductive."[41] Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune praised the supporting cast, writing, "Raul Julia is excellent as Ford's sinister defense attorney. John Spencer, Joe Grifasi, Tom Mardirosian and Sab Shimono are each compelling as investigator, political lackey, prosecutor and coroner."[42]

Owen Gleiberman, writing for Entertainment Weekly, criticized Pakula's direction, stating, "Pakula is good at laying out an intricate, almost mathematical series of events (his best film remains All the President's Men), but he's not big on atmosphere. The movie could have used some of the bowels-of-the-city grit Sidney Lumet brought to Q&A."[43] Dave Kehr, also writing for the Chicago Tribune, stated, "Though it's a handsome film, carefully staged and courageously low-key, the transition to the screen only exaggerates the disposable nature of the material while depriving it of the novel's one stylistic strength, its unreliable narrator."[44]

Accolades

Presumed Innocent received several nominations, with particular recognition for its screenplay by Alan J. Pakula and Frank Pierson. The film received an Edgar Allan Poe Award nomination for Best Motion Picture,[45] and a USC Scripter Award nomination for Pakula, Pierson and the novel by Turow.[46]

| List of accolades | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Award | Date or Year of ceremony | Category | Recipient(s) and nominee(s) | Result | Ref(s) |

| Edgar Allan Poe Awards | 1990 | Best Motion Picture | Alan J. Pakula, Frank Pierson | Nominated | [45] |

| USC Scripter Awards | 1991 | USC Scripter Award | Alan J. Pakula, Frank Pierson (screenplay) Scott Turow (novel) |

Nominated | [46] |

Sequels

The Burden of Proof

Presumed Innocent was followed by a two-part television miniseries, The Burden of Proof (1992). Based on Turow's 1990 novel, the miniseries focuses on defense attorney Sandy Stern (played by Héctor Elizondo), who investigates his wife's past following her apparent suicide. Presumed Innocent co-star Brian Dennehy appeared in a separate role as Stern's brother-in-law.[47] The first chapter of the miniseries aired on the ABC network on February 9, 1992, with the second part airing the following night on February 10.[48]

Innocent

A television sequel, Innocent (2011), was based on Turow's 2010 sequel novel to Presumed Innocent. Set twenty years after the events of the 1990 film, the story follows Rusty Sabich (Bill Pullman), who is charged with the murder of his wife Barbara (Marcia Gay Harden). Innocent aired on TNT on November 30, 2011 as part of the network's "Mystery Movie Night", a collection of six made-for-television films based on best-selling novels.[49]

References

- Broeske, Pat E. (May 20, 1990). "Shoot-Out at the Box Office : Hollywood's awash in money; the upcoming movie budgets are off the charts; what does it all mean? It's action summer!". Los Angeles Times. p. 5. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- "Detail view of Movies Page". American Film Institute. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- Kaplan, David A. (July 22, 1990). "FILM - 'Presumed Innocent' Tackles a Tough Case". The New York Times. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- "Presumed Innocent". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- Klady, Leonard (March 12, 1989). "Presumed Castable". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- Kasindorf, Jeanie (December 1, 1986). "Pollack captures a hot novel". New York. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- Van Gelder, Lawrence (February 2, 1989). "'Innocent' Enthusiasm". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- Appelo, Tim (August 10, 1990). ""Presumed Innocent"'s Alan Pakula". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- Champlin, Charles (July 22, 1990). "Harrison Ford: More Than Slam-Bang : With 'Presumed Innocent,' he continues to evade the type-casting trap set by the mega hits 'Star Wars' and 'Indiana Jones' (Page 2 of 2)". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 6, 2017.

- Duke 2005, p. 162

- Mell 2005, p. 191

- Duke 2005, p. 161

- Champlin, Charles (July 22, 1990). "Harrison Ford: More Than Slam-Bang : With 'Presumed Innocent,' he continues to evade the type-casting trap set by the mega hits 'Star Wars' and 'Indiana Jones' (Page 1 of 2)". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 6, 2017.

- Duke 2005, p. 163

- "Scacchi had crush on Ford in film". Belfast Telegraph. September 26, 2014. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- Hoban 1991, p. 56

- "Winfield: The Trials of an Actor". Los Angeles Times. August 4, 1990. p. 296. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- Duke 2005, p. 164

- Duke 2005, p. 165

- "Presumed Innocent (1990) - Misc Notes". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- Stein, Jeannine (July 27, 1990). "A Full House for 'Presumed Innocent'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- "Presumed Innocent". Soundtrack Collector. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- "Presumed Innocent (1990) - Weekend Box Office Results". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- "Weekend Box Office Results for August 3-5, 1990". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- "1990 Yearly Box Office Results". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- "1990 Yearly Box Office for R Rated Movies". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- "1990 Yearly Box Office Results". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- "1990 Yearly Box Office Results". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- Stevens, Mary (March 22, 1991). "'Presumed Innocent' Leads List Of Wild Ones". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- "DVD: Presumed Innocent (DVD) with Harrison Ford, Brian Dennehy, Bonnie Bedelia, Raul Julia, Greta Scacchi". Tower Records. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- Tooze, Gary W. "Frantic Presumed Innocent Blu-ray - Harrison Ford". DVDBeaver.com. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- "Presumed Innocent". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved May 30, 2020.

- "CinemaScore". cinemascore.com.

- Schickel, Richard (June 24, 2001). "Slow Burner Presumed Innocent". Time. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- Boyar, Jay (July 27, 1990). "Not Surprisingly, 'Presumed Innocent' Is A Good Movie". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- Ebert, Roger (July 27, 1990). "Presumed Innocent Movie Review". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- Benson, Sheila (July 27, 1990). "MOVIE REVIEW : A Solid Case : Film: 'Presumed Innocent' brilliantly captures the novel's essence, and features a tour de force performance from Harrison Ford". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- Travers, Peter (July 27, 1990). "Presumed Innocent". Rolling Stone. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- Maslin, Janet (July 27, 1990). "Review/Film - Who Killed a Prosecutor? Her Lover? Or Another?". The New York Times. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- Rosenbaum, Jonathan (July 27, 1990). "Presumed Innocent". JonathanRosenbaum.net. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- "Presumed Innocent". Variety. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- Siskel, Gene (July 27, 1990). "'Presumed Innocent' Makes A Compelling Case". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- Gleiberman, Owen (July 27, 1990). "Presumed Innocent". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved April 16, 2017.

- Kehr, Dave (July 27, 1990). "'Innocent' Attraction". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- "Edgars Database: Click "Title" and put 'Presumed Innocent', then click "Search"". Edgar Awards. Retrieved January 3, 2017.

- "Scripters 1-5 (1988-1993) - Scripter Films in Leavey Library (DVDs)". University of Southern California. Retrieved January 3, 2017.

- Tucker, Ken (February 7, 1992). "The Burden of Proof". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- "The Burden of Proof". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- Stanley, Alessandra (November 28, 2011). "'Scott Turow's Innocent' on TNT". The New York Times. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

Books

- Duke, Brad (2005). "24. His Bad Hair Day". Harrison Ford: The Films. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-4048-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hoban, Phoebe (November 25, 1991). "Meeting Raul". New York. p. 56. ISSN 0028-7369.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mell, Eila (2005). Casting Might-Have-Beens: A Film by Film Directory of Actors Considered for Roles Given to Others. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-2017-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)