Prehistoric Sweden

Human habitation of present-day Sweden began around 12000 BC. The earliest known people belonged to the Bromme culture of the Late Palaeolithic, spreading from the south at the close of the Last Glacial Period. Neolithic farming culture became established in the southern regions around 4000 BC, but much later further north. About 1700 BC the Nordic Bronze Age began in the southern regions, based on imported metals; this was succeeded about 500 BC by the Iron Age, for which local ore deposits were exploited. Cemeteries are known mainly from 200 BC onward.

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Sweden |

|

|

Prehistoric

|

|

Consolidation

|

|

Great Power

|

|

Enlightenment

|

|

Liberalization

|

|

Modern

|

| Timeline |

|

|

Around the time of Christ, imports of Roman artifacts increased. Agricultural practice spread northward, and permanent field boundaries were constructed in stone. Hillforts became common. A wide range of metalwork, including gold ornaments, are known from the following Migration Period (about 400–550 AD) and Vendel Period (about 550 –790 AD).

Sweden's Iron Age is considered to extend up to the end of the Viking Age, with the introduction of stone architecture and the Christianization of Scandinavia about 1100 AD. The historical record up to then is sparse and unreliable; the first known Roman reports of Sweden are in Tacitus (98 AD). The runic script was developed in the second century, and the brief inscriptions that remain demonstrate that the people of south Scandinavia then spoke Proto-Norse, a language ancestral to modern Swedish.

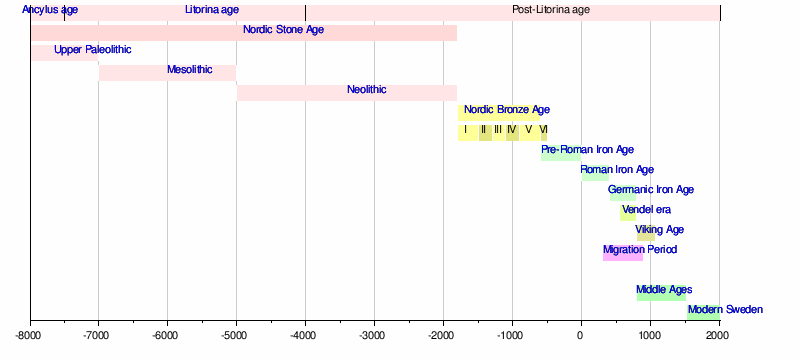

Timeline of Swedish history

Late Palaeolithic and Mesolithic, 12,000–4,000 BC

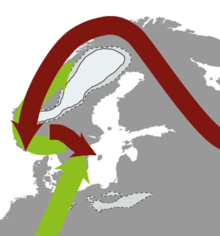

The Pleistocene glaciations scoured the landscape clean and covered much of it in deep quaternary sediments. Therefore, no undisputed Early or Middle Palaeolithic sites or finds are known from Sweden. As far as it is currently known, the country's prehistory begins in the Allerød interstadial c. 12,000 BC with Late Palaeolithic hunting camps of the Bromme culture at the edge of the ice in what is now the country's southernmost province. Shortly before the close of the Younger Dryas (c. 9,600 BC), the west coast of Sweden (Bohuslän) was visited by hunter-gatherers from northern Germany. This cultural group is commonly referred to as the Ahrensburgian and were engaged in fishing and sealing along the coast of western Sweden during seasonal rounds from the Continent. Currently, we refer to this group as the Hensbacka culture and, in Norway, as the Fosna culture group (see: Oxford Journal Hensbacka Schmitt). During the late Preboreal period, colonization continued as people move towards the north-east as the ice receded. Archaeological, linguistic and genetic evidence suggests that they arrived first from the south-west and, in time, also from the north-east and met half-way. The genomes of early Scandinavian hunter-gatherers show that the group from the south and the another one from the northeast eventually mixed in Scandinavia. Besides their cultural differences in e.g. tool making, the two groups also differed in appreance. The populations from the south had dark skin and blue eyes while the groups arriving from the north had light skin and variance in eye color.[2]

An important consequence of de-glaciation was a continual land uplift as the Earth's crust rebounded from the pressure exerted by the ice. This process, which was originally very rapid, continues to this day. It has had the consequence that originally shore-bound sites along much of Sweden's coast are sorted chronologically by elevation. Around the country's capital, for instance, the earliest seal-hunter sites are now on inland mountain tops, and they grow progressively later as one moves downhill toward the sea.

The Late Palaeolithic gave way to the first phase of the Mesolithic in c. 9,600 BC. This age, divided into the Maglemosian, Kongemosian and Ertebølle Periods, was characterised by small bands of hunter-gatherer-fishers with a microlithic flint technology. Where flint was not readily available, quartz and slate were used. In the later Ertebølle, semi-permanent fishing settlements with pottery and large inhumation cemeteries appeared.

Neolithic, 4,000–1,700 BC

Farming and animal husbandry, along with monumental burial, polished flint axes and decorated pottery, arrived from the Continent with the Funnel-beaker Culture in c. 4,000 BC. Whether this happened by diffusion of knowledge or by mass migration or both is controversial. Within a century or two, all of Denmark and the southern third of Sweden became neolithised and much of the area became dotted with megalithic tombs. Farmers were capable of rearing calves to collect milk from cows all year round.[3][4] The people of the country's northern two thirds retained an essentially Mesolithic lifestyle into the first millennium BC. Coastal south-eastern Sweden, likewise, reverted from neolithisation to a hunting and fishing economy after only a few centuries, with the Pitted Ware Culture.

In c. 2,800 BC the Funnel Beaker Culture gave way to the Battle Axe Culture, a regional version of the middle-European Corded Ware phenomenon. Again, diffusion of knowledge or mass migration is disputed. The Battle Axe and Pitted Ware people then coexisted as distinct archaeological entities until c. 2,400 BC, when they merged into a fairly homogeneous Late Neolithic culture. This culture produced the finest flintwork in Scandinavian Prehistory and the last megalithic tombs.

Bronze Age, 1,700–500 BC

Sweden's southern third was part of the stock-keeping and agricultural Nordic Bronze Age Culture's area, most of it being peripheral to the culture's Danish centre. The period began in c. 1,700 BC with the start of bronze importation; first from Ireland and then increasingly from central Europe. Copper mining was never tried locally during this period, and Scandinavia has no tin deposits, so all metal had to be imported though it was largely cast into local designs on arrival. Iron production began locally toward the period's end, apparently as a kind of trade secret among bronze casters: iron was almost exclusively used for tools to make bronze objects.

The Nordic Bronze Age was entirely pre-urban, with people living in hamlets and on farmsteads with single-story wooden long-houses. Geological and topographical conditions were similar to those of today, but the climate was milder.

Rich individual burials attest to increased social stratification in the Early Bronze Age. A correlation between the amount of bronze in burials and the health status of the deceased's bones shows that status was inherited. Battle-worn weapons show that the period was warlike. The elite most likely built its position on control of trade. The period's abundant rock carvings largely portray long rowing ships: these images appear to allude both to trade voyages and to mythological concepts. Areas with rich bronze finds and areas with rich rock art occur separately, suggesting that the latter may represent an affordable alternative to the former.

Bronze Age religion as depicted in rock art centres upon the sun, nature, fertility and public ritual. Wetland sacrifices played an important role. The later part of the period after about 1,100 BC shows many changes: cremation replaced inhumation in burials, burial investment declined sharply and jewellery replaced weaponry as the main type of sacrificial goods.

Iron Age, 500 BC – 1,100 AD

In the absence of any Roman occupation, Sweden's Iron Age is reckoned up to the introduction of stone architecture and monastic orders about 1,100 AD. Much of the period is proto-historical, that is, there are written sources but most hold a very low source-critical quality. The scraps of written matter are either much later than the period in question, written in areas far away, or local and coeval but extremely brief.

Pre-Roman Iron Age, 500–1 BC

The archaeological record for the fifth to third centuries BC is rich in rural settlements and remains of agriculture but very poor in artifacts. This is mainly due to extremely austere burial customs where few people received formal burial and those who did got little in the way of grave goods. There is little indication of any social stratification. Bronze importation ceased almost entirely and local iron production started in earnest.

The climate took a turn for the worse, forcing farmers to keep cattle indoors over the winters, leading to an annual build-up of manure that could now for the first time be used systematically for soil improvement. Fields were however still largely impermanent, leading to the gradual coalescence of vast systems of sunken fields or clearance cairns where only small parts were tilled at any one time.

From the second century BC onward, urn cremation cemeteries and weapon burials with various above-ground stone markers appear, beginning a monumental cemetery record that persists unbroken until the end of the Iron Age. Cemeteries of these roughly 13 centuries are by far the most common type of visible ancient monument in Scandinavia. The reappearance of weapon burial after millennium's hiatus suggests a process of increased social stratification similar to the one at the beginning of the Bronze Age.

Roman Iron Age, 1–400 AD

A Roman attempt to move the Imperial border forward from the Rhine to the Elbe was aborted in 9 AD when Germans under Roman-trained leadership defeated the legions of Varus by ambush in the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest. About this time, a major shift in the material culture of Scandinavia occurred, reflecting increased contact with the Romans. Imported goods, now largely bronze drinking gear, reappear in burials. The early third century sees a brief floruit of very richly equipped graves on a template from Zealand.

Starting in the second century AD, much of southern Sweden's agricultural land was parcelled up with low stone walls. They divided the land into permanent infields and meadows for winter fodder on one side of the wall, and wooded outland where the cattle was grazed on the other side. This principle of landscape organisation survived into the nineteenth century AD.

Hillforts, most of them simple structures on peripheral mountaintops designed as refuges at times of attack, became common toward the end of the Roman Period. War booty finds from western Denmark suggest that warriors from coastal areas of modern Sweden participated in large-scale seaborne raids upon that area and were sometimes soundly defeated.

Sweden enters proto-history with the Germania of Tacitus in 98 AD. Whether any of the brief information he reports about this distant barbaric area was well-founded is uncertain, but he does mention tribal names that appear to correspond with the Swedes and Sami of later centuries. As for literacy in Sweden itself, the runic script was invented among the south Scandinavian elite in the second century, but all that has come down to the present from the Roman Period is curt inscriptions on artefacts, mainly of male names, demonstrating that the people of south Scandinavia spoke Proto-Norse at the time, a language ancestral to modern Swedish and others.

Migration Period, 400–550 AD

The changes in material culture marking the start of the Migration Period appear to coincide with the arrival of the Huns on the continental stage. A brief tumultuous phase ensued during which the Western Roman Empire collapsed and the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantium) held the barbarians at bay only through enormous peace payments. As a consequence, the Scandinavian elite of the time was inundated with gold. It was used to produce some very fine goldsmith work including filigree collars and bracteate pendants. The memory of this Golden Age reverberates through all the main early Germanic poetry cycles, including Beowulf and the Niebelungenlied.

Another feature of the Migration Period that had far-reaching consequences was the development of the first Scandinavian animal art. Inspired by provincial Roman chip-carved belt mounts decorated with lions and dolphins along the edges, Scandinavian artisans of the Migration Period developed first the Nydam Style, and then the highly abstract and sophisticated Style I from c. 450 AD onward.

The Migration Period was long believed to have been a time of crisis and devastation in Scandinavia. In recent decades, however, scholarship has gravitated to the view that the period was in fact one of prosperity and glorious elite culture, but that it ended with a severe crisis, possibly having to do with the 535‒536 AD atmospheric dust event and the concomitant famine.

Vendel Period, 550–800 AD

See also

- Prehistory of Sweden topics

References

- Günther, Torsten; Malmström, Helena; Svensson, Emma M.; Omrak, Ayça; Sánchez-Quinto, Federico; Kılınç, Gülşah M.; Krzewińska, Maja; Eriksson, Gunilla; Fraser, Magdalena; Edlund, Hanna; Munters, Arielle R. (2018-01-09). "Population genomics of Mesolithic Scandinavia: Investigating early postglacial migration routes and high-latitude adaptation". PLOS Biology. 16 (1): e2003703. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.2003703. ISSN 1545-7885. PMC 5760011. PMID 29315301.

- Günther, Torsten; Malmström, Helena; Svensson, Emma M.; Omrak, Ayça; Sánchez-Quinto, Federico; Kılınç, Gülşah M.; Krzewińska, Maja; Eriksson, Gunilla; Fraser, Magdalena; Edlund, Hanna; Munters, Arielle R. (2018-01-09). "Population genomics of Mesolithic Scandinavia: Investigating early postglacial migration routes and high-latitude adaptation". PLOS Biology. 16 (1): e2003703. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.2003703. ISSN 1545-7885. PMC 5760011. PMID 29315301.

- Kristian Sjøgren. "First Scandinavian farmers were far more advanced than we thought" 17 August 2015

- Gron, Kurt J.; Montgomery, Janet; Rowley-Conwy, Peter (2015). "Cattle Management for Dairying in Scandinavia's Earliest Neolithic". PLOS ONE. 10 (7): e0131267. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0131267. PMC 4492493. PMID 26146989.