Pottery in the Indian subcontinent

Pottery in the Indian subcontinent has an ancient history and is one of the most tangible and iconic elements of Indian art. Evidence of pottery has been found in the early settlements of Lahuradewa and later the Indus Valley Civilization. Today, it is a cultural art that is still practiced extensively in Indian subcontinent. Until recent times all Indian pottery has been earthenware, including terracotta.

Hindu traditions historically discouraged the use of pottery for eating off, which probably explains the noticeable lack of traditions of fine or luxury pottery in South Asia, in contrast to East Asia and other parts of Eurasia. Large matki jars for the storage of water or other things form the largest part of traditional Indian pottery, as well as objects such as lamps. Small simple kulhar cups, and also oil lamps, that are disposable after a single use remain common. Today, pottery thrives as an art form in India. Various platforms, including potters' markets and online pottery boutiques have contributed to this trend.

This article covers pottery vessels, mainly from the ancient Indian cultures known from archaeology. There has also been much figurative sculpture and decorative tilework in ceramics in the subcontinent, with the production of terracotta figurines being widespread in different regions and periods. In Bengal in particular, a lack of stone produced an extensive tradition of architectural sculpture for temples and mosques in terracotta and carved brick. The approximately life-size figures decorating gopurams in South India are usually painted terracotta.

Traditional pottery in the subcontinent is usually made by specialized kumhar (Sanskrit: kumbhakära) communities or castes.

History

Mesolithic pottery

Cord-Impressed style pottery belongs to 'Mesolithic' ceramic tradition that developed among Vindhya hunter-gatherers during the Mesolithic period.[1][2] This ceramic style is also found in later Proto-Neolithic phase in nearby regions.[3] This early type of pottery, found at the site of Lahuradewa, is currently the oldest known pottery tradition in South Asia, dating back to 7,000-6,000 BC.[4][5][6][7]

Sothi-Siswal culture

Sothi-Siswal is the site of a Pre-Indus Valley Civilisation settlement dating to as early as 4600 BCE.[8] According to Tejas Garge, Sothi culture precedes Siswal culture considerably, and should be seen as the earlier tradition.[8] Sothi-Siswal culture is named after these two sites, located 70 km apart. As many as 165 sites of this culture have been reported. There are also broad similarities between Sothi-Siswal and Kot Diji ceramics. Kot Diji culture area is located just to the northwest of the Sothi-Siswal area.[9] Sothi-Siswal ceramics are found as far south as the Ahar-Banas culture area in southeastern Rajasthan.

Ahar-Banas culture

Ahar-Banas culture is a Chalcolithic archaeological culture on the banks of Ahar River of southeastern Rajasthan state in India,[10] lasting from c. 3000 to 1500 BC, contemporary and adjacent to the Indus Valley Civilization. Situated along the Banas and Berach Rivers, as well as the Ahar River, the Ahar-Banas people were exploiting the copper ores of the Aravalli Range to make axes and other artefacts. They were sustained on a number of crops, including wheat and barley. The design motifs of the seals are generally quite simple, with wide-ranging parallels from various Indus Civilization sites.

Indus Valley Civilization

Indus Valley Civilization has an ancient tradition of pottery making. Though the origin of pottery in India can be traced back to the much earlier Mesolithic age, with coarse handmade pottery - bowls, jars, vessels - in various colors such as red, orange, brown, black and cream. During the Indus Valley Civilization, there is proof of pottery being constructed in two ways, handmade and wheel-made.[11]

Rangpur culture

Rangpur culture, near Vanala on Saurashtra peninsula in Gujarat, lies on the tip between the Gulf of Khambhat and Gulf of Kutch, it belongs to the period of the Indus valley civilization, and lies to the northwest of the larger site of Lothal.[12] Trail Diggings were conducted by Archeological Survey of India (ASI) during 1931 led by M.S.Vats(madho svarup vats). Later, Ghurye (1939), Dikshit (1947) and S.R.Rao (1953–56) excavated the site under ASI projects.[13] S.R.Rao has classified the deposits into four periods with three sub periods in Harappan Culture, Period II with an earlier Period, Microlithic and a Middle Paleolithic State (River sections) with points, scrapers and blades of jasper. The dates given by S.R.Rao are:

- Period I - Microliths unassociated with Pottery : 3000 BC

- Period II - Harappan : 2000–1500 BC

- Period II B - Late Harappan : 1500–1100 BC

- Period II C - Transition Phase of Harappa : 1100–1000 BC

- Period III - Lustrous Red Ware Period : 1000-800 BC.[13]

Jhukar and Jhangar Phase

Jhukar Phase was a Late Bronze Age culture that existed in the lower Indus Valley, i.e. Sindh, during the 2nd millennium BC. Named after the archaeological type site Jhukar in Sindh, it was a regional form of the Late Harappan Culture, following the mature, urban phase of the civilization.[14]

Jhukar phase was followed by the Jhangar Phase,[14] which is a non-urban culture, characterised by "crude handmade pottery" and "campsites of a population which was nomadic and mainly pastoralist," and is dated to approximately the late second millennium BCE and early first millennium BCE.[15] In Sindh, urban growth began again after approximately 500 BCE.[16]

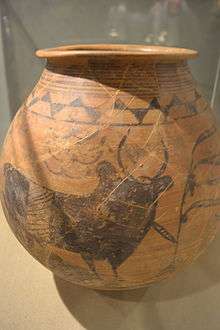

Jar found in Naushahro, 2700-1800 BC.

Jar found in Naushahro, 2700-1800 BC. Storage jar, Mature Harappan period, Chanhudaro, c.2700-2000 BC.

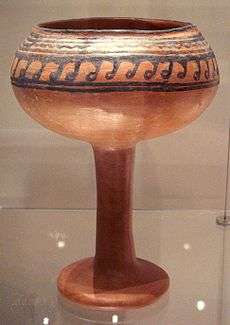

Storage jar, Mature Harappan period, Chanhudaro, c.2700-2000 BC. Indus Valley Civilization, Harappan, Southern Pakistan, c. 2600-2450 BC

Indus Valley Civilization, Harappan, Southern Pakistan, c. 2600-2450 BC

Vedic pottery

Together with the Gandhara grave culture and the Ochre Coloured Pottery culture, the Cemetery H culture is considered by some scholars as a factor in the formation of the Vedic civilization.[17]

Wilhelm Rau (1972) has examined the references to pottery in Vedic texts like the Black Yajur Veda and the Taittiriya Samhita. According to his study, Vedic pottery is for example hand-made and unpainted. According to Kuzmina (1983), Vedic pottery that matches Willhelm's Rau description cannot be found in Asia Minor and Central Asia, though the pottery of Andronovo culture is similar in some respects.[18]

Ochre Coloured Pottery culture

Ochre Coloured Pottery culture (OCP) is a 2nd millennium BC Bronze Age culture of the Indo-Gangetic Plain, extending from eastern Punjab to northeastern Rajasthan and western Uttar Pradesh.[19] It is considered a candidate for association with the early Indo-Aryan or Vedic culture. Early specimens of the characteristic ceramics found near Jodhpura, Rajasthan, date from the 3rd millennium (this Jodhpura is located in the district of Jaipur and should not be confused with the city of Jodhpur). Several sites of culture flourish along the banks of Sahibi River and its tributaries such as Krishnavati river and Soti river, all originating from the Aravalli range and flowing from south to north-east direction towards Yamuna before disappearing in Mahendragarh district of Haryana.[20]

The culture reached the Gangetic plain in the early 2nd millennium. Recently, the Archaeological Survey of India discovered copper axes and some pieces of pottery in its excavation at the Saharanpur district of Uttar Pradesh. The Ochre Coloured Pottery culture has the potential to be called a proper civilisation (e.g., the North Indian Ochre civilisation) like the Harrapan civilisation, but is termed only as a culture pending further discoveries.[21]

Copper Hoard Culture

Copper Hoard Culture occur in the northern part of India mostly in hoards large and small and are believed to date to the later 2nd millennium BCE, although very few derive from controlled and dateable excavation contexts. The doab hoards are associated with the so-called Ochre Coloured Pottery (OCP) which appears to be closely associated with the Late Harappan (or Posturban) phase. These hoard artefacts are a main manifestation of the archaeology of India during the metals age, of which many are deposited in the "Kanya Gurukul museum" in Narela and Haryana.[22]

Cemetery H culture

Cemetery H culture was a Bronze Age cultural regional form in the Punjab region and north-western India, from about 1900 BCE until about 1300 BCE, of the late phase of the Harappan (Indus Valley) civilisation (alongside the Jhukar culture of Sindh and Rangpur culture of Gujarat), and it has also been connected with the early stages of the Indo-Aryan migrations. It was named after a cemetery found in "area H" at Harappa.[23][24][25] According to Kenoyer, the Cemetery H culture "may only reflect a change in the focus of settlement organization from that which was the pattern of the earlier Harappan phase and not cultural discontinuity, urban decay, invading aliens, or site abandonment, all of which have been suggested in the past."[26]

Gandhara grave culture

Gandhara grave culture, also called Swat culture, emerged c. 1600 BC, and flourished c. 1500 BC to 500 BC in Gandhara, which lies in modern-day Pakistan and Afghanistan. It may be associated with early Indo-Aryan speakers as well as the Indo-Aryan migration into the Indian Subcontinent,[17] which came from the Bactria–Margiana region. According to Kochhar, the Indo-Aryan culture fused with indigenous elements of the remnants of the Indus Valley Civilization (OCP, Cemetery H) and gave rise to the Vedic Civilization.[17]

Black and red ware culture

Black and red ware culture (BRW) is a late Bronze Age and early Iron Age archaeological culture of the northern and central Indian subcontinent, associated with the Vedic civilization. In the Western Ganges plain (western Uttar Pradesh) it is dated to c. 1450-1200 BCE, and is succeeded by the Painted Grey Ware culture; whereas in the Central and Eastern Ganges plain (eastern Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Bengal) and Central India (Madhya Pradesh) the BRW appears during the same period but continues for longer, until c. 700-500 BCE, when it is succeeded by the Northern Black Polished Ware culture.[27] In the Western Ganges plain, the BRW was preceded by the Ochre Coloured Pottery culture. The BRW sites were characterized by subsistence agriculture (cultivation of rice, barley, and legumes), and yielded some ornaments made of shell, copper, carnelian, and terracotta.[28] In some sites, particularly in eastern Punjab and Gujarat, BRW pottery is associated with Late Harappan pottery, and according to some scholars like Tribhuan N. Roy, the BRW may have directly influenced the Painted Grey Ware and Northern Black Polished Ware cultures.[29]

Painted Grey Ware

The Painted Grey Ware (PWG) culture is an Iron Age culture of the western Gangetic plain and the Ghaggar-Hakra valley, lasting from roughly 1200 BCE to 600 BCE,[30][31][32] which probably corresponds to the middle and late Vedic period, i.e., the Kuru-Panchala kingdom, the first large state in South Asia after the decline of the Indus Valley Civilization.[33][34] It is a successor of the Black and red ware culture (BRW) within this region, and contemporary with the continuation of the BRW culture in the eastern Gangetic plain and Central India.[27]

Northern Black Polished Ware

.png)

Northern Black Polished Ware (abbreviated NBPW or NBP) is an urban Iron Age culture of the Indian Subcontinent, lasting c. 700–200 BCE, succeeding the Painted Grey Ware culture and Black and red ware culture. It developed beginning around 700 BC, in the late Vedic period, and peaked from c. 500–300 BC, coinciding with the emergence of 16 great states or mahajanapadas in Northern India, and the subsequent rise of the Mauryan Empire.[note 1]

Red Polished Ware (Gujarat)

The Red Polished Ware (RPW) is found in great quantities in Gujarat, especially in the Kathiawar region.[36] Commonly, it consist of domestic forms like cooking pots, and it dates to around first century BC.

But this type of ware also is widely distributed in other places in India. It is found at Baroda, Timberva (Surat), Vadnagar, Vala, Prabhas, Sutrapada, Bhandaria, and many other places. The use of this pottery continued for many centuries.

Early on, the scholars considered this pottery as a diagnostic marker for ‘Indo-Roman trade’, showing the possibility of the Roman empire influence. Also, this type of pottery was identified at sites bordering the Persian Gulf, so it became significant for the research on the Indian Ocean trade.

Red Polished Ware was first identified in 1953 by B. Subbarao.[37] According to him, a "high degree of finish led to consider it as an imported ware or at least an imitation of the Roman Samian Ware".[38]

But in 1966 S. R. Rao in his report on Amreli rejected this possibility of a Roman influence. He insisted on an indigenous origin as none of the forms shared the shapes of Roman prototype.[39] He presented a broad variety of vessel types consisting of clay suitable to that definition. Instead he referred to a similarity of vessels of Black Ware with polished surface [Black Polished ware] from the same site noted in layers beyond the first occurrence of RPW.[40]

According to Heidrun Schenk, the pottery defined as RPW consists of two very distinct functional groups. Thus, the subject needs more precise classification and dating.

One group belongs to the local pottery development of a region around Gujarat—mostly domestic vessels like cooking pots. The core area of this group is western India, but it is also distributed elsewhere on the western littoral of the Indian Ocean.

The other group are the very specialized types of the 'sprinkler' and 'spouted' water jars, that often go together. This special group is widely found in the eastern region of the Indian Ocean, throughout the South Asian subcontinent and South East Asia with many different fabrics. This group represents a later development continuing well into the Middle Ages.

In particular, in Tissamaharama, in the Southern Province of Sri Lanka, a good stratigraphy is found.

Early Red Polished Ware is often associated with the Northern Black Polished ware (NBP), and goes back to 3rd century BC.[40]

Malwa culture

Malwa culture was a Chalcolithic archaeological culture which existed in the Malwa region of Central India and parts of Maharashtra in the Deccan Peninsula. It is mainly dated to c. 1600 – c. 1300 BCE,[41] but calibrated radiocarbon dates have suggested that the beginning of this culture may be as early as c. 2000-1750 BCE.[42] the unique aspect of the Malwa culture is they do not use potter’s wheel instead the whole process is done by hand.[43]

Jorwe culture

Jorwe culture was a Chalcolithic archaeological culture which existed in large areas of what is now Maharashtra state in Western India, and also reached north into the Malwa region of Madhya Pradesh. It is named after the type site of Jorwe. The early phase of the culture is dated to c. 1400-1000 BCE, while the late phase is dated to c. 1000-700 BCE.[44]

Rang Mahal culture

Rang Mahal culture, a post-Vedic culture,[45] is a collection of more than 124 sites spread across Sriganganagar, Suratgarh, Sikar, Alwar and Jhunjhunu districts along the palaeochannel of Ghaggar-Hakra River (Sarasvati-Drishadvati rivers) dating to Kushan (1st to 3rd CE) and Gupta (4th to 7th CE) period, is named after the first archaeological Theris excavated by the Swedish scientists at Rang Mahal village which is famous for the terracota of the early gupta period excavated from the ancient theris in the village.[46][47] The Rang Mahal culture is famed for the beautifully painted vases on red surface with floral, animal, bird and geometric designs painted in black.[48][49]

Turko-Mughal period

The phase of glazed pottery started in the 12th century AD, when Turkic Muslim rulers encouraged potters from Persia, Central Asia and elsewhere to settle in present-day Northern India. Glazed pottery of Persian models with Indian designs, dating back to the Sultanate period, has been found in Gujarat and Maharashtra.

Current era Blue Pottery of Jaipur is widely recognized as a traditional craft of Jaipur, though it is Turko-Persian in origin.[50]

Styles

Over time India's simple style of molding clay went into an evolution. A number of distinct styles emerged from this simple style. Some of the most popular forms of pottery include unglazed pottery, glazed pottery, terracotta, and papier-mache.[51]

Unglazed pottery

Unglazed pottery, the oldest form of pottery practiced in India, is of three types. First is paper thin pottery, biscuit-colored pottery decorated with incised patterns. Next is the scraffito technique, the matka pot is polished and painted with red and white slips along with intricate patterns. The third is polished pottery, this type of pottery is strong and deeply incised, and has stylized patterns of arabesques.[51]

Glazed pottery

Glazed pottery began in the 12th century AD. This type of pottery often has a white background and has blue and green patterns. Glazed pottery is only practiced in parts of the country.[51]

Terracotta sculpture

Terracotta is the term used for unglazed earthenware, and for ceramic sculpture made in it. Indian sculpture made heavy use of terracotta from a very early period (with stone and metal sculpture being rather rare), and in more sophisticated areas had largely abandoned modelling for using moulds by the 1st century BC. This allows relatively large figures, nearly up to life-size, to be made, especially in the Gupta period and the centuries immediately following it. Several vigorous local popular traditions of terracotta folk sculpture remain active today, such as the Bankura horses.[52] Often women prepare clay figures to propitiate their gods and goddesses, during festivals. In Moela deities are created with moulded clay on a flat surface. They are then fired and painted in bright colours. Other parts of India use this style to make figures like horses with riders, sometimes votive offerings.[51]

Comparative chronology

Notes

- After recent excavations at Gotihwa in Nepal, archaeologist Giovanni Verardi by radiocarbon datings says that proto-NBPW is at least from 900 BC. Excavations in India at Ayodhya, Juafardih near Nalanda, and Kolhua near Vaisali, show even earlier radiocarbon datings around 1200 BC. Based on this, historian Carlos Aramayo proposes the following chronology: Proto-NBPW (1200–800 BC); Early NBPW (800–300 BC); and Late NBPW (300–100 BC).[35][35]

References

- D. Petraglia, Michael (26 March 2007). The Evolution and History of Human Populations in South Asia (2007 ed.). Springer. p. 407. ISBN 9781402055614. Retrieved 26 March 2007.

- Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute, Volume 49, Dr. A. M. Ghatage, Page 303-304

- Upinder Singh (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone age to the 12th century. p. 76. ISBN 9788131716779.

- Peter Bellwood; Immanuel Ness (2014-11-10). The Global Prehistory of Human Migration. John Wiley & Sons. p. 250. ISBN 9781118970591.

- Gwen Robbins Schug; Subhash R. Walimbe (2016-04-13). A Companion to South Asia in the Past. John Wiley & Sons. p. 350. ISBN 9781119055471.

- Barker, Graeme; Goucher, Candice (2015). The Cambridge World History: Volume 2, A World with Agriculture, 12,000 BCE–500 CE. Cambridge University Press. p. 470. ISBN 9781316297780.

- Cahill, Michael A. (2012). Paradise Rediscovered: The Roots of Civilisation. Interactive Publications. p. 104. ISBN 9781921869488.

- Tejas Garge (2010), Sothi-Siswal Ceramic Assemblage: A Reappraisal. Ancient Asia. 2, pp.15–40. doi:10.5334/aa.10203

- Asko Parpola, The Roots of Hinduism: The Early Aryans and the Indus Civilization. Oxford University Press, 2015 ISBN 0190226919 p18

- Hooja, Rima (July 2000). "The Ahar culture: A Brief Introduction". Serindian: Indian Archaeology and Heritage Online (1). Archived from the original on 18 August 2000.

- "Pottery". Culturalindia.net. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- Singh, Upinder (August 21, 2008). "A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century". Pearson Education India. p. 214 – via Google Books.

- "Archaeological Survey of India". Asi.nic.in. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- Langer, William L., ed. (1972). An Encyclopedia of World History (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company. pp. 17. ISBN 0-395-13592-3.

- F.R. Allchin (ed.), The Archaeology of Early Historic South Asia: The Emergence of Cities and States (Cambridge University Press, 1995), p.36

- J.M. Kenoyer (2006), "Cultures and Societies of the Indus Tradition. In Historical Roots" in the Making of ‘the Aryan’, R. Thapar (ed.), pp. 21–49. New Delhi, National Book Trust.

- Kochhar 2000, pp. 185-186.

- (see Edwin Bryant, Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture, 2001:211-212)

- Upinder Singh (2008), A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India From the Stone Age to the 12th Century, p.216

- Cultural Contours of India: Dr. Satya Prakash Felicitation Volume, Vijai Shankar Śrivastava, 1981. ISBN 0391023586

- Ali, Mohammad (February 28, 2017). "Copper axes point to an ancient culture story". Thehindu.com. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- Paul Yule (1985). "XX,8". The Bronze Age Metalwork of India. München: Prähistorische Bronzefunde. ISBN 3-406-30440-0.

- M Rafiq Mughal (1990). "Lahore Museum Bulletin, off Print" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-06-26. Retrieved 2018-04-25.

- Kenoyer 1991a.

- Shaffer 1992.

- Kenoyer 1991b, p. 56.

- Franklin Southworth, Linguistic Archaeology of South Asia (Routledge, 2005), p.177

- Upinder Singh (2008), A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India From the Stone Age to the 12th Century, p.220

- Shaffer, Jim. 1993, Reurbanization: The eastern Punjab and beyond. In Urban Form and Meaning in South Asia: The Shaping of Cities from Prehistoric to Precolonial Times, ed. H. Spodek and D.M. Srinivasan. p. 57

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2006-09-08. Retrieved 2005-09-06.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Douglas Q. Adams (January 1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. Taylor & Francis. pp. 310–. ISBN 978-1-884964-98-5.

- Kailash Chand Jain (1972). Malwa Through the Ages, from the Earliest Times to 1305 A.D. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 96–. ISBN 978-81-208-0824-9.

- Geoffrey Samuel, (2010) The Origins of Yoga and Tantra: Indic Religions to the Thirteenth Century, Cambridge University Press, pp. 45–51

- Michael Witzel (1989), Tracing the Vedic dialects in Dialectes dans les litteratures Indo-Aryennes ed. Caillat, Paris, 97–265.

- "Yahoo! Groups". Groups.yahoo.com. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- Patel, A. and S.V. Rajesh (2007) Red Polished Ware (RPW) in Gujarat, Western India – An Archaeological Perspective. Prãgdharã 17 (2006-07): 89-111

- Subbarao, 1953: 32

- Sankalia, Subbarao and Deo, 1958: 46-47

- Rao, 1966: 51

- Heidrun Schenk, Role of ceramics in the Indian Ocean maritime trade during the Early Historical Period. In: Sila Tripati (ed.) Maritime Contacts of the Past – Deciphering Connections Amongst Communities, pp. 143-181. New Delhi: Delta Book World, 2015, academia.edu

- P. K. Basant (2012), The City and the Country in Early India: A Study of Malwa, p.85

- Upinder Singh (2008), A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century, p.227

- "Mitti Mitti Bol: Unearthing India's Rare Pottery". https://www.outlookindia.com/outlooktraveller/. Retrieved 2020-06-20. External link in

|website=(help) - Singh 2008, p. 232.

- Urmila Sant, 1997, Terracotta Art of Rajasthan: From Pre-Harappan and Harappan Times to the Gupta Period, page 59.

- Bikaner history Archived 2012-08-20 at the Wayback Machine

- Hanna Rydh, 1959,Rang Mahal: The Swedish Archaeological Expedition to India, 1952-1954, page 42.

- Chedarambattu Margabandhu, 1991, Indian Archaeological Heritage: Shri K.V. Soundara Rajan Festschrift, page 233.

- Virendra N. Misra, 2007, Rajasthan: prehistoric and early historic foundations, Page 62.

- Subodh Kapoor (2002). "Blue Pottery of Jaipur". The Indian Encyclopaedia. Cosmo Publications. p. 935. ISBN 978-81-7755-257-7. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- "Indian Pottery". Lifestyle.iloveindia.com. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- C. A. Galvin, et al. "Terracotta.", section 5, Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed July 23, 2015, subscription required

- Liverani, Mario (2013). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. Routledge. p. 13, Table 1.1 "Chronology of the Ancient Near East". ISBN 9781134750917.

- Shukurov, Anvar; Sarson, Graeme R.; Gangal, Kavita (7 May 2014). "The Near-Eastern Roots of the Neolithic in South Asia". PLOS ONE. 9 (5): e95714. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...995714G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0095714. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4012948. PMID 24806472.

- Bar-Yosef, Ofer; Arpin, Trina; Pan, Yan; Cohen, David; Goldberg, Paul; Zhang, Chi; Wu, Xiaohong (29 June 2012). "Early Pottery at 20,000 Years Ago in Xianrendong Cave, China". Science. 336 (6089): 1696–1700. Bibcode:2012Sci...336.1696W. doi:10.1126/science.1218643. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 22745428.

- Thorpe, I. J. (2003). The Origins of Agriculture in Europe. Routledge. p. 14. ISBN 9781134620104.

- Price, T. Douglas (2000). Europe's First Farmers. Cambridge University Press. p. 3. ISBN 9780521665728.

- Jr, William H. Stiebing; Helft, Susan N. (2017). Ancient Near Eastern History and Culture. Routledge. p. 25. ISBN 9781134880836.

- Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. ISBN 9788131711200.

- Kenoyer, Jonathan Mark (1991a), "The Indus Valley tradition of Pakistan and Western India", Journal of World Prehistory, 5 (4): 1–64, doi:10.1007/BF00978474

- Kenoyer, Jonathan Mark (1991b), "Urban Process in the Indus Tradition: A preliminary model from Harappa", in Meadow, R. H. (ed.), Harappa Excavations 1986-1990: A multidiscipinary approach to Third Millennium urbanism, Madison, WI: Prehistory Press, pp. 29–60

- Kochhar, Rajesh (2000), The Vedic People: Their History and Geography, Sangam BooksCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shaffer, Jim G. (1992), "The Indus Valley, Baluchistan and Helmand Traditions: Neolithic Through Bronze Age", in Ehrich, R. W. (ed.), Chronologies in Old World Archaeology (Second ed.), Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. I:441–464, II:425–446

Other sources

- Jarrige, Jean-François: 1985, Continuity and change in the North Kachi Plain at the beginning of the 2nd millennium BC, in J Schotsmans and M. Taddei (eds.) South Asian Archaeology, Naples 1983. Instituto Universatirio Orientale.

Further reading

- Bhagat, S. S. 1999. Studio potters of India. New Delhi: All India Fine Arts & Crafts Society.

- Lal, Anupa, Anuradha Ravindranath, Shailan Parker, and Gurcharan Singh. 1998. Pottery and the legacy of Sardar Gurcharan Singh. New Delhi: Delhi Blue Pottery Trust.

- Perryman, Jane. 2000. Traditional pottery of India. London: A. & C. Black.

- Rau, Wilhelm. 1972. Töpferei und Tongeschirr im vedischen Indien Mainz: Verl. d. Akad. d. Wiss. u. d. Lit. - 71 pages.

(Abhandlungen der Geistes- und Sozialwissenschaftlichen Klasse / Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Literatur in Mainz; 1972,10)

- Satyawadi, Sudha. 1994. Proto-Historic Pottery of Indus Valley Civilisation : Study of Painted Motifs.

- Shah, Haku. 1985. Form and many forms of mother clay: contemporary Indian pottery and terracotta : exhibition and catalogue. New Delhi: National Crafts Museum, Office of the Development Commissioner for Handicrafts, Govt. of India.

- Singh, Gurcharan . 1979. Pottery in India. New Delhi: Vikas.

- B. B. Lal (1953). Studies in Early and Mediaeval Indian Ceramics: Some Glass and Glasslike Artefacts from Bellary, Kolhapur, Maski, Nasik and Maheshwar.

.jpg)