Penlop

Penlop (Dzongkha: དཔོན་སློབ་; Wylie: dpon-slob; also spelled Ponlop, Pönlop) is a Dzongkha term roughly translated as governor. Bhutanese penlops, prior to unification, controlled certain districts of the country, but now hold no administrative office. Rather, penlops are now entirely subservient to the House of Wangchuck.

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Bhutan |

|

Monarchy |

|

Government |

Traditionally, Bhutan comprised nine provinces: Trongsa, Paro, Punakha, Wangdue Phodrang, Daga (also Taka, Tarka, or Taga), Bumthang, Thimphu, Kurtoed (also Kurtoi, Kuru-tod), and Kurmaed (or Kurme, Kuru-mad). The Provinces of Kurtoed and Kurmaed were combined into one local administration, leaving the traditional number of governors at eight. While some lords were penlops, others held the title Dzongpen (Dzongkha: རྗོང་དཔོན་; Wylie: rjong-dpon; also "Jongpen," "Dzongpön"), a title also translated as "governor."[1] Other historical titles, such as "Governor of Haa," were also awarded.

Under the dual system of government, penlops and dzongpens were theoretically masters of their own realms but servants of the Druk Desi. In practice, however, they were under minimal central government control, and the Penlop of Trongsa and Penlop of Paro dominated the rest of the local lords.[2] And while all governor posts were officially appointed by Shabdrung Ngawang Namgyal, later the Druk Desi, some offices such as the Penlop of Trongsa were de facto hereditary and appointed within certain families. Penlops and dzongpens often held other government offices such as Druk Desi, Je Khenpo, governor of other provinces, or a second or third term in the same office.[3]

The heir apparent and King of Bhutan still hold the title Penlop of Trongsa for a period, as this was the original position held by the House of Wangchuck before it obtained the throne.

History

Under Bhutan's early theocratic dual system of government, decreasingly effective central government control resulted in the de facto disintegration of the office of Shabdrung after the death of Shabdrung Ngawang Namgyal in 1651. Under this system, the Shabdrung reigned over the temporal Druk Desi and religious Je Khenpo. Two successor Shabdrungs – the son (1651) and stepbrother (1680) of Ngawang Namgyal – were effectively controlled by the Druk Desi and Je Khenpo until power was further splintered through the innovation of multiple Shabdrung incarnations, reflecting speech, mind, and body. Increasingly secular regional lords (penlops and dzongpens) competed for power amid a backdrop of civil war over the Shabdrung and invasions from Tibet, and the Mongol Empire.[4] The penlops of Trongsa and Paro, and the dzongpons of Punakha, Thimphu, and Wangdue Phodrang were particularly notable figures in the competition for regional dominance.[4][5]

Within this political landscape, the Wangchuck family originated in the Bumthang region of central Bhutan.[6] The family belongs to the Nyö clan, and is descended from Pema Lingpa, a Bhutanese Nyingmapa saint. The Nyö clan emerged as a local aristocracy, supplanting many older aristocratic families of Tibetan origin that sided with Tibet during invasions of Bhutan. In doing so, the clan came to occupy the hereditary position of Penlop of Trongsa, as well as significant national and local government positions.[7]

The Penlop of Trongsa controlled central and eastern Bhutan; the rival Penlop of Paro controlled western Bhutan; and dzongpons controlled areas surrounding their respective dzongs. Eastern dzongpens were generally under the control of the Penlop of Trongsa, who was officially endowed with the power to appoint them in 1853.[3]:106, 251 The Penlop of Paro, unlike Trongsa, was an office appointed by the Druk Desi's central government. Because western regions controlled by the Penlop of Paro contained lucrative trade routes, it became the object of competition among aristocratic families.[7]

Although Bhutan generally enjoyed favorable relations with both Tibet and British India through the 19th century, extension of British power at Bhutan's borders as well as Tibetan incursions in British Sikkim defined politically opposed pro-Tibet and pro-Britain forces.[8] This period of intense rivalry between and within western and central Bhutan, coupled with external forces from Tibet and especially the British Empire, provided the conditions for the ascendancy of the Penlop of Trongsa.[7]

After the Duar War with Britain (1864–65) as well as substantial territorial losses (Cooch Behar 1835; Assam Duars 1841), armed conflict turned inward. In 1870, amid the continuing civil wars, Penlop Jigme Namgyal of Trongsa ascended to the office of Druk Desi. In 1879, he appointed his 17-year-old son Ugyen Wangchuck as Penlop of Paro. Jigme Namgyal reigned through his death 1881, punctuated by periods of retirement during which he retained effective control of the country.[9]

The pro-Britain Penlop Ugyen Wangchuck ultimately prevailed against the pro-Tibet and anti-Britain Penlop of Paro after a series of civil wars and rebellions between 1882 and 1885. After his father's death in 1881, Ugyen Wangchuck entered a feud over the post of Penlop of Trongsa. In 1882, at the age of 20, he marched on Bumthang and Trongsa, winning the post of Penlop of Trongsa in addition to Paro. In 1885, Ugyen Wangchuck intervened in a conflict between the Dzongpens of Punakha and Thimphu, sacking both sides and seizing Simtokha Dzong. From this time forward, the office of Desi became purely ceremonial.[9]

Trongsa Penlop Ugyen Wangchuck, firmly in power and advised by Kazi Ugyen Dorji, accompanied the British expedition to Tibet as an invaluable intermediary, earning his first British knighthood. Penlop Ugyen Wangchuck further garnered knighthood in the KCIE in 1904. Meanwhile, the last officially recognized Shabdrung and Druk Desi had died in 1903 and 1904, respectively. As a result, a power vacuum formed within the already dysfunctional dual system of government. Civil administration had fallen to the hands of Penlop Ugyen Wangchuck, and in November 1907 he was unanimously elected hereditary monarch by an assembly of the leading members of the clergy, officials, and aristocratic families. His ascendency to the throne ended the traditional dual system of government in place for nearly 300 years. It also marked the end of the traditional position of independent penlops.[8][10] The title Penlop of Trongsa – or Penlop of Chötse, another name for Trongsa – continued to be held by crown princes.[11]

Penlops of Trongsa

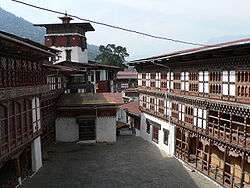

Penlops of Trongsa, also called "Tongsab" (Dzongkha: ཀྲོང་སརབ་; Wylie: krong-sarb), are based in Trongsa, modern day Trongsa District in central Bhutan. In the 19th century, the Penlop of Trongsa emerged as one of the two most powerful offices in the realm, having marginalized all others but the Penlop of Paro. By the ascension of Jigme Namgyel (also called Deb Nagpo, "the Black Deb")[12]:132 in 1853, the office was virtually hereditary, held firmly by the House of Wangchuck of the Nyö clan. Many members of the family occupied other government offices before, during, or after the position of Trongsa Penlop.

| Number | Name | Dates |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tongsab Chogyal Minjur Tenpa | 1646–? |

| 2 | Tongsab Sherub Lhendup (Namlungpa) | (fl. 1667) |

| 3 | Tongsab Zhidhar (Druk Dhendup) | (fl. 1715) |

| 4 | Tongsab Dorji Namgyel (Druk Phuntsho)[Trongsab 1] | ? |

| 5 | Tongsab Sonam Drugyel (Pekar) | (fl. 1770) |

| 6 | Tongsab Jangchhub Gyeltshen | ? |

| 7 | Tongsab Konchhog Tenzin | ? |

| 8 | Tongsab Ugyen Phuntsho | ? |

| 9 | Tongsab Tshoki Dorji | ?–1853 |

| 10 | Tongsab Samdrup Jigme Namgyel[Trongsab 2] | 1853–1870 |

| 11 | Tongsab Dungkar Gyeltshen | ? |

| 12 | Tongsab Gongsar Ugyen Wangchuck | 1882–1907 |

| 13 | Tongsab Gyalsay Jigme Wangchuck | 1923–?? |

| 14 | Tongsab Gyalsay Jigme Dorji Wangchuk | 1946–?? |

| 15 | Tongsab Gyalsay Jigme Singye Wangchuck | 1972–?? |

| 16 | Tongsab Gyalsay Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck | 2004–present |

Notes:

| ||

Penlops of Paro

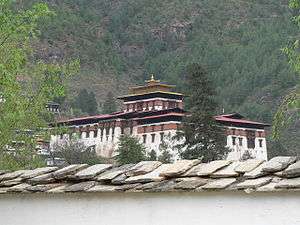

The Penlops of Paro were also known as "Parob" (Dzongkha: སྤ་རོབ་; Wylie: spa-rob). As the office flourished, so did competition with the pro-British Penlop of Trongsa. Ultimately, the independence of the Penlop of Paro ended in merger with the House of Wangchuck.

| Number | Name |

|---|---|

| 1 | Parob Tenzin Drukda |

| 2 | Parob Ngawang Chhoda |

| 3 | Parob Ngawang Peljor |

| 4 | Parob Druk Dondub |

| 5 | Parob Samten Pekar |

| 6 | Parob Ngawang Gyeltshen |

| 7 | Parob Phuntsho |

| 8 | Parob Pema Wangda |

| 9 | Parob Tenzin Lhundub |

| 10 | Parob Sherub Wangchuck |

| 11 | Parob Tharpa |

| 12 | Parob Dalub Rinchhen |

| 13 | Parob Tyochung |

| 14 | Parob Ling Phuntsho |

| 15 | Parob Tagzi Dolma |

| 16 | Parob Tshulthrim Namgyel ("Penlop Haap") |

| 17 | Parob Yonten Rinchhen |

| 18 | Parob Nyima Dorji |

| 19 | Parob Thinley Zangpo |

| 20 | Parob Tshewang Norbu |

| 21 | Parob Ugyen Wangchuck[Parob 1] |

| 22 | Parob Thinley Tobgay |

| 23 | Parob Dawa Peljor[12]:123, 132 [Parob 2] |

| 24 | Parob Tshering Peljor[Parob 3] |

| 25 | Parob Gyalsay Jigme Dorji Wangchuck[Parob 4] |

| 26 | Parob Gyalsay Namgyel Wangchuck[Parob 5] |

Notes:

| |

Penlops of Daga

The Penlop of Daga, or "Dagab" (Dzongkha: དར་དཀརབ་; Wylie: dar-dkarb), was based in Daga, a town in modern Dagana District.

| Number | Name |

|---|---|

| 1 | Dagab Tenpa Thinley |

| 2 | Dagab Tshulthrim Jungney |

| 3 | Dagab Rigzin Lhundub |

| 4 | Dagab Rabten |

| 5 | Dagab Tenzin Wangpo |

| 6 | Dagab Tshering Dondub |

| 7 | Dagab Dorji Norbu |

| 8 | Dagab Tashi Gangpa |

| 9 | Dagab Tshewang Phuntsho |

| 10 | Dagab Samten Dorji |

| 11 | Dagab Jamo Serpo |

| 12 | Dagab Doyon Chelwa |

| 13 | Dagab Sithub |

| 14 | Dagab Tshewang Dorji |

References

- Madan, P. L. (2004). Tibet, Saga of Indian Explorers (1864–1894). Manohar Publishers & Distributors. p. 77. ISBN 978-81-7304-567-7. Retrieved 2011-08-14.

- Lawrence John Lumley Dundas Zetland (Marquis of); Ronaldsha E., Asian Educational Services (2000). Lands of the thunderbolt: Sikhim, Chumbi & Bhutan. Asian Educational Services. p. 204. ISBN 978-81-206-1504-5. Retrieved 2011-08-10.

- Dorji, C. T. (1994). "Appendix III". History of Bhutan based on Buddhism. Sangay Xam, Prominent Publishers. p. 200. ISBN 978-81-86239-01-8. Retrieved 2011-08-12.

-

-

- Crossette, Barbara (2011). So Close to Heaven: The Vanishing Buddhist Kingdoms of the Himalayas. Vintage Departures. Random House Digital, Inc. ISBN 978-0-307-80190-6. Retrieved 2011-08-10.

- Padma-gliṅ-pa (Gter-ston) (2003). Harding, Sarah (ed.). The life and Revelations of Pema Lingpa. Snow Lion Publications. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-55939-194-8. Retrieved 2011-08-10.

- Europa Publications (2002). Far East and Australasia. Regional surveys of the world: Far East & Australasia (34 ed.). Psychology Press. pp. 180–81. ISBN 978-1-85743-133-9. Retrieved 2011-08-08.

- Brown, Lindsay; Mayhew, Bradley; Armington, Stan; Whitecross, Richard W. (2007). Bhutan. Lonely Planet Country Guides (3 ed.). Lonely Planet. pp. 38–43. ISBN 978-1-74059-529-2. Retrieved 2011-08-09.

-

- Rennie, Frank; Mason, Robin (2008). Bhutan: Ways of Knowing. IAP. p. 176. ISBN 978-1-59311-734-4. Retrieved 2011-08-10.

- White, J. Claude (1909). "Appendix I – The Laws of Bhutan". Sikhim & Bhutan: Twenty-One Years on the North-East Frontier, 1887–1908. New York: Longmans, Green & Co. pp. 11, 272–3, 301–10. Retrieved 2010-12-25.

- Dorji Wangdi (2004). "A Historical Background of the Chhoetse Penlop" (PDF). The Tibetan and Himalayan Library online. Thimphu: Cabinet Secretariat. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-02-14. Retrieved 2011-02-20.