Polytrichum

Polytrichum is a genus of mosses — commonly called haircap moss or hair moss — which contains approximately 70 species that cover a cosmopolitan distribution. (Less common vernacular names include bird wheat and pigeon wheat.)

| Polytrichum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male gametophytes bearing antheridia. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Bryophyta |

| Class: | Polytrichopsida |

| Order: | Polytrichales |

| Family: | Polytrichaceae |

| Genus: | Polytrichum Hedw. |

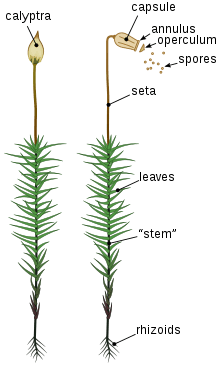

The genus Polytrichum has a number of closely related sporophytic characters. The scientific name is derived from the Ancient Greek words polys, meaning "many", and thrix, meaning "hair". This name was used in ancient times to refer to plants with fine, hairlike parts, including mosses, but this application specifically refers to the hairy calyptras found on young sporophytes. There are two major sections of Polytrichum species. The first — section Polytrichum — has narrow, toothed, and relatively erect leaf margins. The other — section Juniperifolia — has broad, entire, and sharply inflexed leaf margins that enclose the lamellae on the upper leaf surface.[1][2]. Polytrichum reproduce by vegetative and sexual methods.

Appearance

With a distinct appearance the Common Hair Cap Moss gets its name from the hairs that cover, or cap, the calyptra where each spore case is held (1). Looking down on it, the Common Hair Cap Moss has a star shaped appearance because of the pointed leaves arranged spirally at right angles around a stiff stem (3). Like other mosses, it is generally a dark green colour and doesn’t grow very tall. The Common Hair Cap Moss has no woody tissue so it only grows from 4–20 cm tall (2). Growing like a lush green carpet, the average life span of this moss is three to five years, although ten has been recorded, and even dead the moss remains intact, and is what makes up the lower portion of this organism

Physiology

Mosses in the genus Polytrichum are endohydric, meaning water must be conducted from the base of the plant. While mosses are considered non-vascular plants, those of Polytrichum show clear differentiation of water conducting tissue. One of these water conducting tissues is termed the hydrome, which makes up the central cylinder of stem tissue. It consists of cells with a relatively wide diameter called hydroids, which conduct water. This tissue is analogous to xylem in higher plants. The other tissue is called leptome, which surrounds the hydrome, contains smaller cells and is analogous to phloem.[3]

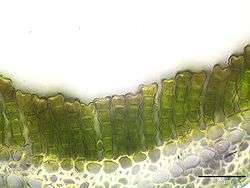

Another characteristic feature of the genus is its parallel photosynthetic lamellae on the upper surfaces of the leaves. Most mosses simply have a single plate of cells on the leaf surface, but those of Polytrichum have more highly differentiated photosynthetic tissue. This is an example of a xeromorphic adaption, an adaptation for dry conditions. Moist air is trapped in between the rows of lamellae, while the larger terminal cells act to contain moisture and protect the photosynthetic cells. This minimises water loss as relatively little tissue is directly exposed to the environment, but allows for enough gas exchange for photosynthesis to take place. The microenvironment between the lamellae can host a number of microscopic organisms such as parasitic fungi and rotifers. Additionally, the leaves will curve and then twist around the stem when conditions become too dry, this being another xeromorphic adaptation. It is speculated that the teeth along the leaf's edge may aid in this process, or perhaps also that they help discourage small invertebrates from attacking the leaves.[3]

Classification

The genus Polytrichastrum was separated from Polytrichum in 1971 based on the structure of the peristome (which controls spore release).[4][5] However, molecular and morphological data from 2010 support moving some species back into Polytrichum.[4][6]

Species

|

|

|

|

References

- Smith Merrill, Gary L. (2007), "Polytrichum", in Flora of North America Editorial Committee, eds. 1993+ (ed.), Flora of North America, 27, New York & Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Crum, Howard Alvin; Anderson, Lewis Edward (1981), Mosses of Eastern North America, Columbia University Press, pp. 1281–1282, ISBN 0-231-04516-6

- Silverside, A.J. (2005), Biodiversity Reference: Polytrichum commune Hedw., University of Paisley, archived from the original on 2005-12-28, retrieved 2008-02-16

- Bell, N. E.; Hyvonen, J. (2010), "A phylogenetic circumscription of Polytrichastrum (Polytrichaceae): Reassessment of sporophyte morphology supports molecular phylogeny", American Journal of Botany, 97 (4): 566–78, doi:10.3732/ajb.0900161, PMID 21622419

- 1. Polytrichastrum G. L. Smith, Flora of North America

- Bell, NE; Hyvönen, J (2010), "Phylogeny of the moss class Polytrichopsida (BRYOPHYTA): Generic-level structure and incongruent gene trees", Molecular Phylogenetics & Evolution, 55 (2): 381–98, doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2010.02.004, PMID 20152915

- Polytrichum, USDA PLANTS

- BLWG Verspreidingsatlas Mossen online (in Dutch)

9. Sumukh C Prakash in his one of interview