Police tribunal (Belgium)

The police tribunal (Dutch: politierechtbank, French: tribunal de police, German: Polizeigericht) is the traffic court and trial court which tries minor contraventions in the judicial system of Belgium. It is the lowest Belgian court with criminal jurisdiction (in addition to some limited civil jurisdiction). There is a police tribunal for each judicial arrondissement ("district"), except for Brussels-Halle-Vilvoorde, where there are multiple police tribunals due to the area's sensitive political situation. Most of them hear cases in multiple seats per arrondissement. As of 2018, there are 15 police tribunals in total, who hear cases in 38 seats. Further below, an overview is provided of all seats of the police tribunal per judicial arrondissement.[1][2]

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Belgium |

|

|

|

|

Federal Cabinet |

|

|

.jpg)

A police tribunal is chaired by a judge of the police tribunal, more commonly called police judge (Dutch: politierechter, French: juge de police, German: Polizeirichter). Police judges are professional, law-trained magistrates who are, like all judges in Belgium, appointed for life until their retirement age. The police judges hear cases as single judges, but are always assisted by a clerk. There is also a prosecutor from the public prosecutor's office present who prosecutes (suspected) offenders in the criminal cases the police tribunal hears. The defendants, as well as any victim seeking civil damages, can be assisted or represented by counsel, but this is not required. Lawyers or notaries can act as locum tenens police judge whenever a judge is absent. The organisation of the police tribunals and the applicable rules of civil procedure and criminal procedure are laid down in the Belgian Judicial Code and the Belgian Code of Criminal Procedure. Mind the fact that, despite their name, the police tribunals are not organisationally related to the police.[1][2][3]

Jurisdiction and procedures

The police tribunals only have jurisdiction over their part of the territory of their judicial arrondissement.

Contraventions

The police tribunals have original jurisdiction over all contraventions (Dutch: overtreding, French: contravention, German: Übertretung), which are the least serious types of crimes under Belgian law (such as nightly noise nuisance or acts of violence that did not cause any injury). Contraventions can be punished with a maximum prison sentence of 7 days or a maximum fine of 1 to 200 euro (as of January 2017). An important exception to this jurisdiction of the police tribunal are drug offences, over which the correctional division of the tribunal of first instance always has original jurisdiction, irrespective of their severity. In addition, the prosecutor can prosecute delicts (Dutch: wanbedrijf, French: délit, German: Vergehen), which is the category of crimes more serious than contraventions under Belgian law (comparable to misdemeanors or lesser felonies), as contraventions through the process of contraventionalisation. This requires the prosecutor to assume the existence of extenuating circumstances.[1][4]

Traffic-related cases

The police tribunals also have original jurisdiction over all traffic-related crimes, from minor parking violations to driving under the influence to serious crimes such as unintentional vehicular homicide. The prison sentences and fines to which one can be sentenced for these crimes strongly exceed the otherwise very limited sentences the police tribunals can impose over contraventions. The police tribunals can also impose traffic-specific penalties, such as a driver's license suspension. Not all traffic-related crimes are immediately brought before the police tribunal; for most minor traffic violations a police officer can issue a traffic ticket which includes a fine to be paid. If the (suspected) offender contests the ticket or fails to pay the fine, the prosecutor will usually prosecute the suspect before the police tribunal. Aside from criminal jurisdiction, the police tribunals have original jurisdiction as well over any civil damages or insurance disputes arising from traffic accidents, irrespective of the amount in value. It is a feature of the Belgian judicial system in general, that courts and tribunals having jurisdiction over criminal cases can also decide on any civil damages sought by a victim (referred to as the civil party) in the case. However, even if the prosecutor does not bring any charges against the person responsible for a traffic accident, the police tribunal will still hear any civil action related to the case. As a consequence of the police tribunals' broad jurisdiction over all traffic-related cases, both civil and criminal, the large majority of the cases they hear are traffic-related.[1][4][5]

Specific crimes

The police tribunals' jurisdiction also extends over some (usually minor) crimes defined by specific laws or ordinances, which assign the original jurisdiction over these crimes exclusively to the police tribunals. Examples of these crimes include those defined by the laws on public intoxication, compulsory education, river fishing or railway transportation, those defined by the Belgian Rural Code or Belgian Forestry Code, or those defined by a local ordinance from a municipal council or provincial council.[1][4]

Appellate jurisdiction

Aside from establishing local ordinances of which the violation is punished as a contravention, Belgian law also allows municipalities to establish municipal administrative sanctions (Dutch: gemeentelijke administratieve sanctie, French: sanction administrative communale, German: kommunale Verwaltungssanktion) themselves. These are intended for a municipality to be able to act against public nuisances, such as littering, obstructing public roads or parking violations, in a flexible manner. A municipal administrative sanction can be an administrative fine (not exceeding 350 euro), the administrative suspension or withdrawal of a permit issued by the municipality, or the forced closure of an establishment (either temporary or permanent). An administrative fine can be imposed by a municipal officer, the other sanctions can only be imposed by a municipality's college of mayor and aldermen. Community service and mediation exist as alternatives for a municipal administrative sanction. Appeals against such a sanction are heard by the police tribunals, except in the case of minors, in which case the appeal is heard by the juvenile division of the tribunal of first instance.[1][5][6]

The police tribunals hear appeals against other kinds of administrative penalties as well, such as fines or stadium bans issued under the Belgian football law. The appeals against administrative fines and penalties are heard as civil cases.[1][5]

Search warrants

Lastly, the police tribunals are responsible for issuing search warrants related to the inspection and enforcement of specific laws, such as the laws on taxation, customs duties, gambling, animal welfare or environmental protection. The general authority to issue search warrants in criminal investigations lies with the investigative judges at the tribunals of first instance.

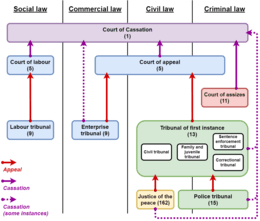

Appeal

Judgements made by the police tribunals can be appealed to the correctional divisions of the tribunals of first instance, or to the civil divisions of these tribunals if the case has a purely civil nature. The judgements delivered on these appeals by the tribunals of first instance are final; they cannot be further appealed to the courts of appeal. However, an appeal in cassation to the Court of Cassation on questions of law, not on questions of fact, is still possible on these final judgements.[7][8]

The judgements made by the police tribunals in petty civil cases where the disputed amount does not exceed 2,000 euro (as of September 2018) cannot be appealed (except for an appeal in cassation). In the judgements made on appeals against administrative sanctions or penalties, the police tribunals have already exercised appellate review; these judgements are thus final as well and cannot be further appealed (except for an appeal in cassation).[8]

Statistics

According to the statistics provided by the College of the courts and tribunals of Belgium, a total of 258,976 suspects were prosecuted in all police tribunals in 2016. The police tribunals rendered a total of 237,441 judgements in these criminal cases. Of these judgements, a total of 11,009 were appealed to the tribunals of first instance. Additionally, the police tribunals decided on 364 search warrant requests in total as well in 2016. Due to incomplete data collection, no reliable statistics could be provided on civil judgements for 2016, but in 2015 a total of 6,813 new civil cases were opened at all police tribunals, next to 11,854 pending cases that originated from before 1 January 2015. A judgement was delivered in 7,816 civil cases in 2015 as well.[9][10]

List of police tribunals

As of 2018, there is a seat of a police tribunal in the following municipalities (per judicial arrondissement):

Arrondissement of East Flanders:

Arrondissement of Luxembourg:

(*): Due to the sensitive political situation in and around Brussels, there are four police tribunals in the arrondissement of Brussels which are all independent from each other.

See also

References

- "Politierechtbank" [Police tribunal]. www.tribunaux-rechtbanken.be (in Dutch). College of the courts and tribunals of Belgium. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- "Judiciary – Organization" (PDF). www.dekamer.be. Parliamentary information sheet № 22.00. Belgian Chamber of Representatives. 1 June 2014. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- "Judiciary – Breakdown of law" (PDF). www.dekamer.be. Parliamentary information sheet № 21.00. Belgian Chamber of Representatives. 26 June 2014. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- "Articles 137–140 of the Belgian Code of Criminal Procedure". www.ejustice.just.fgov.be (in Dutch). Belgian official journal. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- "Articles 601bis–601ter of the Belgian Judicial Code". www.ejustice.just.fgov.be (in Dutch). Belgian official journal. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- "Gemeentelijke administratieve sancties" [Municipal administrative sanctions]. www.besafe.be (in Dutch). Federal Public Service Interior. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- "Articles 172–177 of the Belgian Code of Criminal Procedure". www.ejustice.just.fgov.be (in Dutch). Belgian official journal. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- "Articles 577, 602 & 617 of the Belgian Judicial Code". www.ejustice.just.fgov.be (in Dutch). Belgian official journal. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- "Politierechtbanken – Jaar 2016" [Police tribunals – Year 2016] (PDF). www.tribunaux-rechtbanken.be. Yearly statistics of the courts and tribunals (in Dutch). College of the courts and tribunals of Belgium. June 2018. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- "Kerncijfers van de gerechtelijke activiteit – Jaren 2010-2017" [Key figures of judicial activity – Years 2010-2017] (PDF). www.tribunaux-rechtbanken.be (in Dutch). College of the courts and tribunals of Belgium. August 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 May 2019. Retrieved 3 May 2019.