Pisa Altarpiece

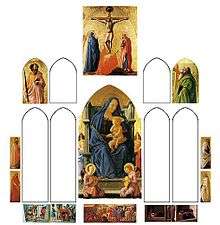

The Pisa Altarpiece (Italian: Polittico di Pisa) was a large multi-paneled altarpiece produced by Masaccio for the chapel of Saint Julian in the church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Pisa. The chapel was owned by the notary Giuliano di Colino, who commissioned the work on February 19, 1426 for the sum of 80 florins. Payment for the work was recorded on December 26 of that year. The altarpiece was dismantled and dispersed to various collections and museums in the 18th century, but an attempted reconstruction was made possible due to a detailed description of the work by Vasari in 1568.[1]

It was a tempera painting on a gold ground and wood panel. It originally had at least five compartments organised in two registers, making ten main panels, of which only four are known to have survived. Another four side panels and three predella panels (two of which had a double scene) are now in the Gemäldegalerie, Berlin. The altarpiece's central panel was Madonna and Child with Angels, produced in collaboration with Masaccio's brother Giovanni and with Andrea di Giusto, now in the National Gallery, London.

Eleven panels are known as of 2010, and they are insufficient to reconstruct the whole work with certainty. In particular four standing figures of saints flanking the central panel are missing. Vasari says these were the saints shown in the predella narrative scenes: Peter, John the Baptist, Julian and Nicholas. In particular it is unclear if these larger saints occupied the more traditional individual framed compartments, as proposed by C. Gardner von Teuffel and others, or stood in a unified field with the central Virgin and Child, as proposed by John Shearman, which was to be become the usual style in the following decades.[2]

Surviving panels

Eleven surviving panels of the altarpiece, which is the only documented work by Masaccio, are in various museums.[3] Scholars hypothesize the reconstruction of the altarpiece based on a very complete description by Vasari.[4]

The eleven surviving panels are:

- Upper Register: Crucifixion (Naples); Saint Paul (Pisa); Saint Andrew (Malibu)

- Lower Register: Madonna and Child with Angels (London); Augustine, Jerome, two Carmelite saints (all Berlin)

- Predella (all Berlin): Adoration of the Magi; two scenes of the Crucifixion of St Peter and Martyrdom of St John the Baptist; two scenes from the legends of St Julian and St Nicholas

Upper Register

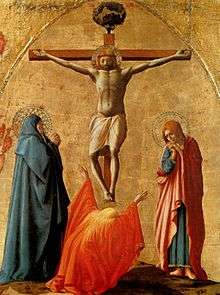

Crucifixion

The Crucifixion was placed above the central panel of the altarpiece, underlining the sacrificial (Eucharistic) nature of the central panel.[5] Although the panel unnaturalistically represents the narrative against a gold background (a medieval formula for representing sacred scenes), Masaccio creates an effect of reality by depicting the event from below, as the viewer standing before the altar truly saw it. In this way, he attempts to tie the viewer to the scene, to make the sacred accessible to the ordinary Christian.

Saints

Now in the Museo Nazionale di Pisa, the panel of Paul of Tarsus is the only portion of the commissioned work which remains in Pisa. It is usually reconstructed as being one of two flanking panels to the left of the Crucifixion. St Andrew was one of two flanking panels to the right of the Crucifixion and is now in the Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

St Paul, now in Pisa

St Paul, now in Pisa

Lower Register

Madonna and Child with Angels

The altarpiece's central panel was Madonna and Child with Angels, produced in collaboration with Masaccio's brother Giovanni and with Andrea di Giusto. It was painted in 1426.[6] The panel is in a very damaged state and smaller than its original size; it has lost perhaps as much as 8 cm. at the bottom and 2-2.5 cm. at each side.[7]

The painting contains six figures: the Madonna and Child and four angels. The Madonna is the centre figure and is larger than any of the others to signify her importance. Christ sits on her knees, eating grapes offered to him by his mother. The grapes represent the wine which was drunk at the Last Supper, symbolising Christ's blood.[6] Although he is an exceedingly babyish baby (in comparison to the babies of Masaccio's immediate predecessors, like Lorenzo Monaco or Gentile da Fabriano), the grapes are a symbol of his blood – like the red wine of Communion – which indicates Christ's awareness of his eventual death. The Madonna looks sorrowfully at her child, as she also realises his fate.

In many ways the style of the painting is traditional; the expensive gold background and ultramarine draperies of the Virgin, her enlarged scale, and her hierarchical presentation (ceremoniously enthroned) all fit within the late-medieval formulas for the representation of Mary and Jesus in glory. In other ways, however, the painting is a step away from International Gothic in the sense that Masaccio has created a more realistic approach to the subject:

- The faces are more realistic and not idealised.

- The baby Jesus is less of a small man and more childlike.

- An attempt at creating depth has been attempted by Masaccio's placement of the two background angels and through the use of linear perspective in the throne.

- Modeling is clearly visible as the light source is coming from the left of the painting.

- The Madonna is a bulky figure, deriving from classical models, and her drapery has larger and more naturalistic folds that shape her body.

Masaccio has used linear perspective to create pictorial space; it can be seen on the orthogonal on the cornice of her throne. The vanishing point is at the child's foot. The reason for this is that the work was originally located above a representation of the Adoration of the Magi, in which one of the magi kisses Jesus' foot.

Although the paintings are noticeably different (the subjects are clothed differently and on different chairs) the Madonna is more or less in the same position in both works. This parallelism is designed to make viewers have the same attitude as the magus when looking at the Madonna and Child. They are imagined to be kneeling in front of Mary, and could easily lean forward to kiss the foot of Jesus.

Masaccio has also used the overlapping of figures and objects to create pictorial space, like the two angels in the foreground overlapping the throne and the throne overlapping the two angels in the background.

Flanking saints

These are four panels all now in the Gemäldegalerie, Berlin, all 38 cm × 12 cm (15.0 in × 4.7 in). They show Augustine of Hippo, Jerome and two unknown Carmelite monk saints, one bearded and the other tonsured.

Saint Augustine, Berlin

Saint Augustine, Berlin St Jerome, Berlin

St Jerome, Berlin Bearded Carmelite saint, Berlin

Bearded Carmelite saint, Berlin Carmelite saint, Berlin

Carmelite saint, Berlin

Predella

This was placed below the central panel or panels; probably there were only the three surviving panels, according to most reconstructions. They are about 21 cm × 61 cm (8.5 in × 24 in) and now in the Gemäldegalerie, Berlin. They show the Adoration of the Magi, especially praised by Vasari and presumed to have been the central panel, two scenes of the Crucifixion of St Peter and Martyrdom of St John the Baptist, and two scenes from the legends of St Julian and St Nicholas in the third panel. These stories come from compilations such as the Golden Legend. In the last, at left Julian the Hospitaller kills his parents, after having been misinformed by the devil, shown in the centre. At right Saint Nicholas is secretly pushing gold through the bedroom window of two poor girls, to provide a dowry for them.

Martyrdoms of St Peter and John the Baptist, Berlin

Martyrdoms of St Peter and John the Baptist, Berlin Adoration of the Magi, Berlin

Adoration of the Magi, Berlin Scenes from the legends of St Julian and St Nicholas, Berlin

Scenes from the legends of St Julian and St Nicholas, Berlin

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Polittico di Pisa (Masaccio). |

- Giorgio Vasari, Le vite de' più eccellenti pittori, scultori ed architettori, ed. Gaetano Milanesi, Florence, 1906, II, 292.; online translation

- Central area, per John Shearman

- Documents published in James Beck, Masaccio: The Documents, Locust Valley, NY, 1978, Appendix, 31–50.

- Giorgio Vasari, Le vite de' più eccellenti pittori, scultori ed architettori, ed. Gaetano Milanesi, Florence, 1906, II, 292.

- Jill Dunkerton et al., Giotto to Dürer: Early Renaissance Painting in the National Gallery, New Haven, 1991, 248–251.

- "The Virgin and Child". National Gallery.

- Jill Dunkerton and Dillian Gordon, "The Pisa Altarpiece," in Carl Brandon Strehlke, ed.The Panel Paintings of Masolino and Masaccio: The Role of Technique, Milan, 2002, 91–93.

External links

- Masaccio, Virgin and Child Enthroned, Smarthistory at Khan Academy, March 20, 2013