Andrea di Giusto

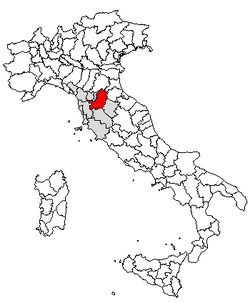

Andrea di Giusto (c. 1400- 2 September 1450, Florence), rarely also known as Andrea Manzini or Andrea di Giusto Manzini was a Florentine painter of the late Gothic to early Renaissance style in Florence and its surrounding countryside. Andrea was heavily influenced by masters Lorenzo Monaco, Bicci di Lorenzo, Masaccio, and Fra Angelico, and tended to mix and match the motifs and techniques of these artists in his own work.[1] Andrea was an eclectic painter and is considered a minor master of Florentine early Renaissance art. Andrea trained under Bicci di Lorenzo as a Garzone. He painted his most significant works, three altarpieces, in the Florentine contado, or countryside; these altarpieces were created for Sant’Andrea a Ripalta in Figline, Santa Margarita in Cortona, and the Badia degli Olivetani di San Bartolomeo alle Sacce near Prato. Aside from his major altarpieces, Andrea painted several Frescoes over the course of his career. He, along with other minor masters, are also known to have provided several different types of art, including triptychs and frescoes, for Romanesque pievi, or rural churches with baptistries. Moreover, he was well known for several types of smaller craft objects, such as small tabernacles. He is said to have worked between 1420 and 1424 under Bicci di Lorenzo on paintings for Santa Maria Nuova. He is said to have worked with Masaccio in painting the Life of San Giuliano for the Polyptych of Pisa, including the painting of the Madonna and Child, in 1426. He also appears to have collaborated in 1445 with Paolo Uccello in the Capella dell'Assunta in the Prato Cathedral.[2] In 1428, he is listed as a member of the Arte dei Medici e Speziali guild in Florence as "Andrea di Giusto di Giovanni Bugli".[3] His son, Giusto d'Andrea, was also a painter and worked with Neri di Bicci and Benozzo Gozzoli. Andrea died in Florence in 1450.[4]

Training

Andrea was trained under Bicci di Lorenzo. Bicci's sizable workshop enjoyed an established relationship, believed to have begun in 1418, with Santa Maria Nuova, a Florentine hospital with an adjoining church that provided a great number of commissions to local artists. Bicci and his associates began with craft work before being commissioned to create sculptures and frescoes in addition to this site. In 1424, Bicci's workshop accomplished relief figures for the interior of the church at Santa Maria Nuova and further decorated and gilded an exterior sculpture attributed to Dello di Niccolò Delli.[5] While completing these more prized commissions, Bicci and his workshop continued to produce lesser craft works in order to sustain the workshop financially, which inadvertently lead to renown in the creation of some of these craft items, such as gilded candlesticks and sculptures. In fact, it appears that Bicci's first commission as an independent master was for a set of gilded candlesticks in 1416.[5] Moreover, Bicci's workshop produced a sinopia and fresco of the Madonna and Child for Santa Maria Nuova; Bicci himself painted the Consecration of St. Egidio for the church's exterior, receiving payment for the work in October 1424.[5] Through these various commissions, Bicci's workshop also developed an acumen for frescoes and panel painting.

Andrea himself is mentioned regarding payment during this period as an assistant to Bicci in 1424, suggesting his involvement in several of the crafts and works created for Santa Maria Nuova. Moreover, in the later 1430s when Andrea had established himself as an independent artist, he painted a small tabernacle, a Madonna and Child with two Angels for Santa Maria Nuova, now located in the Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze.[5] The small tabernacle form appears to have been one of Andrea's early specialties, and as such public tabernacles, as well as ones made specifically for patrons, were likely a significant source of income for him and other minor masters.[6] After training with Bicci, Andrea worked under Masaccio in Pisa until 1427.[7]

Major works

Altarpieces

Andrea's career is marked by three major altarpieces created in the Florentine contado, or countryside: Sant’Andrea a Ripalta in Figline, Santa Margarita in Cortona, and the Badia degli Olivetani di San Bartolomeo alle Sacce near Prato.[8] A fourth, less significant (low) altarpiece in Florence may also be included in this group.

Prato

The Prato altarpiece was created in 1435 and was inspired by Lorenzo Monaco’s Monte Oliveto altarpiece from 1410. Because Andrea had been influenced early in his career by Lorenzo's work, he attempted to replicate Lorenzo's work as accurately as possible, particularly with regard to the altarpiece's figures and drapery.[9] In fact, the altarpiece's patron sought an essential copy of Lorenzo's work and therefore commissioned Andrea to complete it. While the composition, coloring, and drapery of the altarpiece starkly recall Lorenzo's style, the figures more clearly recall Bicci di Lorenzo's style.[10] Andrea employed many different colors in his chiaroscuro technique, which provides depth for the composition while also uniting the panels. The composition reveals the influence of Fra Angelico, particularly in Madonna's face, Lorenzo Monaco, and Gentile Bellini.[10] On the predella, Andrea created the Naming of the Baptist, imitating one of Fra Angelico’s compositions. While Fra Angelico involved each figure in the scene's drama, Andrea opted to de-lever the scene, creating a calmer composition using lighter colors.

Sant'Andrea a Ripalta

In 1436, Andrea painted a triptych altarpiece for Sant'Andrea a Ripalta in Figline entitled Adoration of the Magi with Four Saints. The work was commissioned by Bernardo di Tomaso di Ser Ristoro, a member of the Serristor family, descendants of a politically prominent Florentine notary. The central panel recalls Gentile Bellini's Adoration, though in a simplified manner, featuring the Madonna and child along with the three Magi. The Virgin Mary and baby Jesus reflect the influence of Fra Angelico and Masaccio through her body positioning and coloring and the composition of Jesus Christ. The predella features the four saints, Andrew, John the Baptist, James Major, and Anthony Abbot. Their composition again recalls the work of Masaccio, Masolino da Panicale and Fra Angelico; St. Andrew Baptizing strongly recalls Massacio's Brancacci Chapel St. Peter Baptizing, while the baptismal audience recalls Fra Angelico's depiction of figures surrounding St. Peter in the Linaioli tabernacle.[11] The triptych's landscapes also harken back to the Brancacci chapel, particularly through the landscapes of Masolino and Masaccio. This altarpiece is one of Andrea's most notable works because it was likely very expensive, including significant gold leaf, a Gothic frame, bold colors, and several figures and panels.[11] Moreover, because the work borrowed so much from contemporary major masters, the composition appears much less traditional and conservative than many of Andrea's other works. It is one of Andrea's most complex creations.

Madonna della Cintola

Andrea dated the Madonna della Cintola in the Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze in 1437. The main panel features a kneeling St. Thomas, while the Death of the Virgin is depicted in the center of the predella; both compositions betray significant influence from Fra Angelico. The St. Catherine is influenced by a lost work by Masolino da Panicale portraying the same character. In a turn away from Lorenzo Monaco’s typical influence on Andrea, the drapery in this altarpiece is subdued rather than animated, as in Lorenzo’s composition, though Lorenzo’s influence on Andrea’s depiction of form remains intact.

Santa Lucia dei Magnoli

In 1436, Andrea was received the meaningful sum of 60 florini (Florin) for the completion of a low altarpiece for Santa Lucia dè Magnoli in Florence, created for the altar of Lapa Benozzi or Lapo di Andrea Benozzo. In the same year, he is recorded as a member of the Arte di Calimala, which performed the administrative work surrounding the commission. While the threshold for a major altarpiece in terms of price hovered around 100 florini, this sizable sum suggests a multi-paneled and meaningfully detailed work.[5] Significantly, there are no known instances of minor masters being commissioned to create high altarpieces in Florence; this fact makes Andrea’s achievements as a minor master noteworthy. Furthermore, it is important to note that Andrea, along with other minor masters, created many more works in the Florentine contado than in Florence proper. As such, only one of Andrea’s altarpieces is found in Florence, while three are found in the contado.

Frescoes

Andrea painted three frescoes toward the end of his life in the Cappella dell'Assunta in Prato Cathedral. While the "Prato Master" planned the compositions, Andrea completed the frescos using the miniaturist technique, meaning that the designs were conceived on a small scale and then magnified. Andrea used tiny, parallel brushstrokes to detail the panels, much in the style of Fra Angelico's pradella panels.[5] Although Andrea had become an assistant to Masaccio, who frequently painted on a grand scale, Andrea never learned to do so and therefore used the same approach whether painting a wall or a small panel.[12] In the style of Fra Angelico, Andrea included an elliptical figure composition in the Stoning of St. Stephen that uses alternating heights and actions to convey a rhythm among the figures.[12] However, while Fra Angelico preferred to spread figures out between the foreground and background, Andrea chose to keep the figures in the foreground, losing some depth consequently. The Marriage of the Virgin panel recalls both Fra Angelico and Masaccio, particularly with regard to the composition of the onlookers.

Andrea painted two frescos at Santa Croce, Florence, located in the hallways leading from the Pazzi Chapel and the novitiate depicting the Crucifixion and a Christ Portacroce,[13] and worked with Bicci di Lorenzo on several frescoes in 1423 and 1424 in Florence according to payment records.[14] He completed the final scenes of Paolo Uccello's frescoes in St. Stephen's Chapel of the Assumption (Cappella dell'Assunta) in the Prato Duomo. He is also said to have painted a panel for the Florentine Opera del Duomo, paid for by private citizens. The Opera's reluctance to provide public patronage for Andrea's work reflects the institution's preference for major over minor masters.[5]

Santa Maria del Carmine Altarpiece and Predella

Andrea worked with Masaccio on the altarpiece for the Carmine church in Pisa in 1427, painting the panels of its predella, the lower, supporting section of the altarpiece, with the Legend of St. Julian and the Charity of St. Nicholas. He also assisted Masaccio in painting the central panel of the altarpiece, entitled the Madonna and Child with Angels (Madonna and Child (Masaccio)), now located at the National Gallery.

Late phase

The final stage of Andrea's career is marked by stoic, flat figures lacking the vivacity he had earlier attempted to portray, typified by his triptych altarpiece for San Michele in Moriano (ca. 1445).[5] Andrea again synthesises the various techniques of major masters, though creates a composition lacking in several elements he had previously mastered. While he may have attempted to convey tranquillity through the relatively bland colour scheme and composition, the triptych falls short when compared to his earlier works.

Impact of the contado

Andrea created the vast majority of his artistic works in the Florentine contado, or countryside. The differences in economics of the Florentine city and its contado account for a great deal of the differences between the Renaissance's minor and major masters. Very few, if any major masters painted in the contado, leaving the region in the control of the minor masters.[5] While the minor masters simply were never commissioned to paint the high altarpieces of Florentine churches, their craftsmanship was revered in the contado. In these ways, while the contado is generally understood to contain "minor works", this terminology is deceptive due to the significant works of minor masters located there, including those of Andrea di Giusto. Moreover, the minor masters were often able to obtain compensation similar to what a major master might garner in the same location. In order to support themselves, the minor masters were more reliant on less revered art forms, such as the production of small tabernacles and other small crafts. Furthermore, the minor masters tended to practice a more conservative style, allowing the major masters to take bold artistic risks in major cities while they created more traditional works. Patrons in the contado tended to prefer conservative works to bold ones, prizing craftsmanship and efficiency over artistic innovation. As artists bridging the gap between the early and high Renaissance styles, the minor masters connected the Trecento and the Quattrocento and Renaissance, incorporating some of the major masters’ innovations while remaining firmly planted in more conservative style. In this way, Andrea's works can be considered partly a product of his location in the contado; perhaps if he had been deemed a major master, he would have been able to take greater, bolder risks with his craft.

Influence of Masaccio

Andrea draws significant influence from Masaccio, with whom he worked on the Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence altarpiece, although his works are considered outside the standard Quattrocento style to which Masaccio subscribed.[5] Scholars note his desire to capture Masaccio's gravitas, stoicism, and general sculptural forms, tending to focus on one of these components while incorporating the techniques of other major masters.[5] In fusing these techniques, Andrea was likely responding to the changing preferences of his patrons as well as the emergent humanism characteristic of the Italian Renaissance; he most often did so by dramatizing the light in his compositions through Chiaroscuro, or the use of shadow and light, or including humanistic motifs like classical themes and sculptural forms. One significant example of Masaccio's influence on Andrea is evident in a comparison of Andrea's Madonna (Museo Stibbert) to Masaccio's Meterzza St. Anne; Andrea imitates Masaccio's use of chiaroscuro to light the painting starkly from left to right, a characteristic unusual to his work.[15] However, in a similar Child of the Madonna painting (Albrighi Collection, Florence), Andrea depicts the baby in a pose often used by Masaccio, although few other elements of the painting recall the major master. In this way, while Andrea was indeed influenced by Masaccio, the influence is partially obscured firstly by Andrea's choice to combine elements characteristic of several contemporary major masters simultaneously, and secondly by his distinct personal style, which is apparent even in heavily influenced works.[15]

Critical reception

Art historians tend to take a negative view of Andrea's work, and particularly call into question his artistic inspiration, citing the great deal of imitation pervasive in his works.

"There is a small typical Madonna by Andrea di Giusto from S. Giusto a Montalbino that shows him as inept and threadbare as in his other works."[16]

"The artistic career of Andrea di Giusto...reveals the incredible ease with which he mastered every old and new element, in order to compensate for his lack of imagination."[1][17]

Sales at auction

On 5 June 2008, Andrea's Praying Angel sold for $15,000 at Sotheby's art auction in New York. The painting exemplifies the influence Fra Angelico had on Andrea later in the latter's career.[18]

Andrea's The Madonna and Child with two Angles sold at Christie's art auction in London on the 3 December 2008 for £55,250, vastly outperforming its price estimate of £12,000 - £18,000.[19] Subsequently, it was sold at Koller art auction in Zurich on 23 September 2016 for CHF 55,000, less than it was purchased for at Christie's.[20]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Andrea di Giusto. |

- P. Dal Poggetto, p. 44, Arte in Valdelsa, Certaldo, 1963

- Comune di Figline e Incisa Valdarno Archived 2016-09-23 at the Wayback Machine.

- Il Museo di Palazzo Pretorio a Prato, by AA. VV., Giunti editore, page 112.

- Associazione Storico Culturale Sant'Agostino.

- Bailey, H. E. (1992). The other renaissance: Florentine painting in the shadow of Masaccio (Order No. 9316305). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (303964947).

- Bailey, H. E. (1992). The other renaissance: Florentine painting in the shadow of masaccio, pg. 41(Order No. 9316305). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (303964947).

- Beck, James H (1978). Masaccio, the documents. Locust Valley, NY, USA: J. J. Augustin. p. 22.

- Bailey, H. E. (1992). The other renaissance: Florentine painting in the shadow of Masaccio, pg 46 (Order No. 9316305). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (303964947).

- Bailey, H. E. (1992). The other renaissance: Florentine painting in the shadow of masaccio, pg 74 (Order No. 9316305). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (303964947).

- Bailey, H. E. (1992). The other renaissance: Florentine painting in the shadow of masaccio, pg 125 (Order No. 9316305). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (303964947).

- Bailey, H. E. (1992). The other renaissance: Florentine painting in the shadow of masaccio, pg 57 (Order No. 9316305). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (303964947).

- Bailey, H. E. (1992). The other renaissance: Florentine painting in the shadow of masaccio, pg 129 (Order No. 9316305). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (303964947).

- Bailey, H. E. (1992). The other renaissance: Florentine painting in the shadow of masaccio, pg 36 (Order No. 9316305). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (303964947).

- WALSH, B. B. (1979). The Fresco Paintings Of Bicci Di Lorenzo (Order No. 7921335). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (302921232).

- Bailey, H. E. (1992). The other renaissance: Florentine painting in the shadow of masaccio, pg 88 (Order No. 9316305). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (303964947).

- R. Offner, p.174, The Burlington Magazine, LXIII, July-Dec, 1933.

- Fremantle, Richard (1975). Florentine Gothic painters from Giotto to Masaccio : a guide to painting in and near Florence, 1300 to 1450. London: Secker & Warburg. p. 513.

- "giusto, andrea di p ||| old master paintings ||| sotheby's n08453lot3nv9pen". www.sothebys.com. Retrieved 2017-03-07.

- "Andrea Manzini, called Andrea di Giusto (active Florence 1400-1450) , The Madonna and Child with two Angels". www.christies.com. Retrieved 2017-03-07.

- "Objektsuche künftiger Auktionen". www.kollerauktionen.ch. Retrieved 2017-03-07.