Pico Duarte

Pico Duarte is the highest peak in the Dominican Republic, and in all the Caribbean. It is 85 kilometres (53 miles) northeast of the region's lowest point, Lake Enriquillo, in the Cordillera Central range, the largest in the country. The Cordillera Central extends from the plains between San Cristóbal and Baní to the northwestern peninsula of Haiti, where it is known as Massif du Nord. The highest elevations of the Cordillera Central are found in the Pico Duarte and Valle Nuevo massifs.

| Pico Duarte | |

|---|---|

Pico Duarte | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 3,098 m (10,164 ft) [1] |

| Prominence | 3,098 m (10,164 ft) [1] |

| Isolation | 941 km (585 mi) |

| Listing |

|

| Coordinates | 19°01′23″N 70°59′53″W [1] |

| Geography | |

| Location | San Juan, Dominican Republic |

| Parent range | Cordillera Central |

| Climbing | |

| First ascent | 1851 by Robert H. Schomburgk |

| Easiest route | Hike |

History

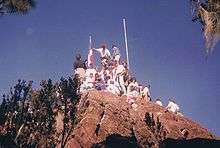

The first reported climb was made in 1851 by the British consul Sir Robert Hermann Schomburgk.[2] He named the mountain "Monte Tina" and estimated its height at 3,140 m. In 1912, Father Miguel Fuertes dismissed Schomburgk's calculations after climbing La Rucilla and judging it to be the tallest summit of the island. A year later, Swedish botanist Erik Leonard Ekman sided with Schomburgk's estimate, and called the sister summits "Pelona Grande" and "Pelona Chica" ("Big Bald One" and "Small Bald One", respectively). During the Rafael Trujillo Molina regime, the taller of the two was called "Pico Trujillo". After the dictator's death, it was renamed Pico Duarte, in honor of Juan Pablo Duarte, one of the Dominican Republic's founding fathers. At the summit is an east-facing bronze bust of Duarte atop a stone pedestal, next to a flagpole that flies the Dominican flag and a cross.

Geography

The mountain's elevation was debated for decades, up until the mid-1990s, when it was still held to be 3,175 meters high. In 2003, it was measured by a researcher using GPS technology, and it was found to be 3,098 meters tall.[3] The official elevation as recorded by Dominican government agencies is 3,087 meters, a measurement that has been confirmed by several groups of hikers using personal GPS consoles (the most recent verified one in January 2005). Despite this, SRTM data indicates that the professional survey is probably more accurate. It is only a few meters taller than La Pelona, its twin which stands at 3,084, and from which it is separated by a col between summits that is approximately 1.5 km wide, and is officially named Valle del Baíto, but unofficially called Valle de Lilís. The col's mean elevation is 2,950 meters.

Ecology

The area has a climate that very few would associate as typical of a Caribbean island, with cool temperatures all year round, going several degrees below freezing during winter nights.

The mountain and the surrounding landscape are covered in pino de cuaba (Pinus occidentalis) forests. The pines frequently host the epiphytes guajaca (Tillandsia spp.) and the parasitic Dendropemon pycnophyllus. Some areas, like the Valle de Lilís, are treeless meadows of tussock-like pajones (Danthonia domingensis). The understory is composed of shrub such as Lyonia heptamera, Myrica picardae, Myrsine coriacea, Ilex tuerkheimii, Garrya fadyenii and Baccharis myrsinites. All of these species are adapted to the acidic soil of the area.[4]

Birds seen in the area include the endemic Hispaniolan palm crow (Corvus palmarum palmarum), Antillean siskin (Carduelis dominicensis), rufous-throated solitaire (Myadestes genibarbis), Hispaniolan crossbill (Loxia megaplaga) (abundance directly related to the Hispaniolan pine cone crop), and Hispaniolan trogon (Priotelus roseigaster); at lower elevations the Hispaniolan amazon (Amazona ventralis), scaly-naped pigeon (Patagioenas squamosa) and golden swallow (Tachycineta euchrysea) can be seen. There are two extant mammals endemic to Hispaniola[5] whose remaining range includes the broadleaf forests of lower elevations: the primarily nocturnal Hispaniolan solenodon (Solenodon paradoxus)[6] and the Hispaniolan hutia (Plagiodontia aedium).[7] Both are endangered and rarely seen. Wild boars, descendants of animals introduced to the island during the colonial period, have been reported.[8]

A wildfire in 2003 altered the landscape of a large section of the eastern side of the mountain. As of 2008, the hillside of charred trees is now a new-growth forest. While thousands of charred trees are still standing, a large variety of indigenous grasses and small plants are now growing.

Climbing information

There is a system of trails leading up to the summit, with trailheads at several locations (see topo map for their final stretches to the summit). The easiest access is from the town of La Ciénaga, near Jarabacoa. The trail is 23.1 km (14.4 mi) to the summit, with a total elevation change of 1,977 meters, and a shelter 5 km away from the summit at La Comparticion.[9] Tourist-friendly travel agencies in the town of Jarabacoa can help arrange trips from this trailhead, using mules in their employ to help lug food, sleeping bags and supplies for the overnight stay in the shelter.

A few fresh water springs labeled "potable" are along the trail, but water filters or purifying tablets are recommended. The majority of hikers travel by this route.

A trailhead northwest of the town of San Juan de la Maguana is the starting point for four-day (three-night) trips that end at the Ciénaga trailhead (or, for an extra day of hiking, back at the starting location), which are run entirely by local Dominicans who cook the food provided, and help campers along the way. Each night is spent in shelters, and due to the distance traveled, riding by mule-back is strongly encouraged. Far off the beaten path, it is highly unlikely that anyone else can be seen on the trail until the merge with the trail from La Ciénaga. Fluency in Spanish is recommended for anyone that attempts this route.

According to Dominican Park Service representatives in La Cienaga, while approximately 1,000 hikers visit Pico Duarte during each of the months of December and January; only about 10 to 15 people a day hike the mountain during off-season months.

References

- Maizlish, Aaron (2003). "Central America and Caribbean Ultra Prominence Page". Peaklist.org. Retrieved 2012-04-06.

- Baker, Christopher P. (2009). Explorer's Guide Dominican Republic: A Great Destination. Explorer's Great Destinations. Countryman Press. p. 327. ISBN 978-1-58157-907-9.

- Orvis, K. H. (2003). "The Highest Mountain in the Caribbean: Controversy and Resolution via GPS". Caribbean Journal of Science. 39 (3): 378–380. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.403.4046.

- Myers, R.; O'Brien, J.; Mehlman, D.; Bergh, C. (November 2004). Fire Management Assessment of the Highland Ecosystems of the Dominican Republic (Report). The Nature Conservancy. Download available at Conservation Gateway.

- Woods, C. A. (1981). "Last endemic mammals in Hispaniola". Oryx. 16 (2): 146–152. doi:10.1017/S0030605300017105.

- Turvey, S.; Incháustegui, S. (2008). "Solenodon paradoxus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008: e.T20321A9186243. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T20321A9186243.en.

- Turvey, S.; Incháustegui, S. (2008). "Plagiodontia aedium". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008: e.T17460A7086930. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T17460A7086930.en.

- Pariser, Harry S. (1994). The Adventure Guide to the Dominican Republic. Hunter Publishing. p. 163. ISBN 978-1-55650-629-1.

- "Hiking Pico Duarte". Summit Post. Retrieved 10 May 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pico Duarte Nacional park. |

- Pico Duarte @ SummitPost.org

- The Pico Duarte: The Caribbean's Summit

- "Top of the Caribbean: Climbing Pico Duarte, 2012 travelogue in three parts at Uncommon Caribbean website.