Piceance Basin

The Piceance Basin is a geologic structural basin in northwestern Colorado, in the United States. It includes geologic formations from Cambrian to Holocene in age, but the thickest section is made up of rocks from the Cretaceous Period. The basin contains reserves of coal, natural gas, and oil shale. The name likely derives from the Shoshoni word /piasonittsi/ meaning “tall grass” (/pia-/ ‘big’ and /soni-/ ‘grass’).[1]

Hydrocarbon resources

In 2016 USGS released an assessment of the resources of the Mancos Shale of the Piceance Basin in Colorado and Utah, "a total of assessed technically recoverable mean resources of 74 million barrels of shale oil, 66.3 trillion cubic feet of gas, and 45 million barrels of natural gas liquids."[2]

Natural gas

The basin has come to increasing public attention in recent years because of widespread drilling to extract natural gas. The primary target of gas development has been the Williams Fork Formation of the Mesaverde Group, of Cretaceous age. The Williams Fork is a several-thousand-foot thick section of shale, sandstone and coal deposited in a coastal plain environment. The formation has long been known to contain natural gas. The sandstone reservoirs have low permeability and limited areal extent, however, which made gas wells uneconomic in the past.

In 1969 an atomic device was detonated in a well drilled into the Williams Fork Formation southwest of Rifle, Colorado in an attempt to fracture the rock and enable commercial extraction of natural gas. Project Rulison, as it was called, was a failure.

Advances in hydraulic fracturing within the past decade, along with higher gas prices, have made gas wells broadly economic in the area. In 2007 the basin contained five of the top 50 US gas fields in proved reserves (Grand Valley #16, Parachute #24, Mamm Creek #27, Rulison #29, and Piceance Creek #46).[3]

Oil shale

Increasing demand for energy resources has spurred interest in energy alternatives such as oil shale. The Piceance Basin contains one of the thickest and richest oil shale deposits in the world and is the focus of most on-going oil shale research and development extraction projects in the U.S. The Piceance Basin has an estimated 1.525 trillion barrels of in-place oil shale resources, and an estimated 43.3 billion tons of in-place nahcolite resources in the Piceance Basin. This mineral is embedded with oil shale in many areas.[4]

On 2 April 2009 The U.S. Geological Survey updated its assessment of in-place oil shale resources in the Piceance Basin in western Colorado. This new assessment is about 50 percent larger than the 1989 assessment of about one trillion barrels. Almost all of this increase is due to assessments of new geographic areas and subsurface zones that had too little data for previous research and assessments. "For the first time in 20 years, we have an updated assessment of in-place oil shale in the Piceance Basin of Colorado," said US Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar. "The USGS scientific report shows significant quantities of oil locked up in the shale rocks of the Piceance Basin. I believe it demonstrates the need for our continued research and development efforts."[5]

Production

The Pacific Connector Gas Pipeline was proposed to carry hydrocarbon production to the Jordan Cove Energy Project in Coos Bay, Oregon. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission denied the project a permit on March 11, 2016. The reason given was that Veresen had not demonstrated the need for the project, and that the benefits from the project would not outweigh the harm done to individual landowners to justify the use of eminent domain. The pipeline's backers had not yet found buyers for the natural gas.[6] On March 25, Veresen announced that they had found a buyer for the gas that would be exported, which was a consortium of Japanese utilities. They suggested they would appeal the decision by FERC, and they had 30 days from the March 11 decision to do so.[7] As of May 2018 energy producers hoped to revive the project.[8]

Geology

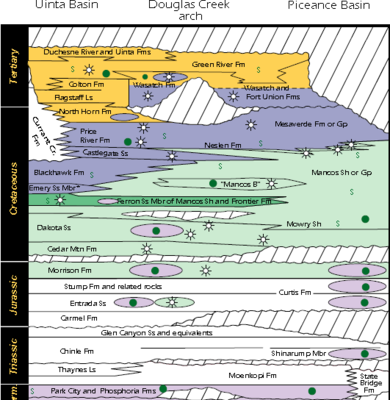

The Piceance Basin forms a geologic structural basin, and is the source of commercial oil and gas production. Separated from the Uinta Basin by the Douglas Creek Arch, both basins formed during the Laramide Orogeny, and are bounded by the Charleston-Nebo thrust fault, the Uinta Basin boundary fault, and the Grand Hogback monocline. According to the USGS Uinta-Piceance Assessment Team, "The black-shale facies of the Green River Formation is the main petroleum system of Tertiary age whereas the Mahogany zone of the Green River Formation is a minor component. The Cretaceous Mancos Group and equivalent rocks are the main source of Cretaceous oil and a major contributor of gas in the basin, whereas the Upper Cretaceous Mesaverde is a lesser contributor of oil but a significant source for gas. Ferron Sandstone coals are known to be a source of coalbed methane. The most prominent source of oil from Paleozoic rocks is the Permian Phosphoria Formation.[9][10]

See also

References

- CASTANEDA, TERRI (November 2006). "Native American Placenames of the United States:Native American Placenames of the United States". The Public Historian. 28 (4): 100–102. doi:10.1525/tph.2006.28.4.100. ISSN 0272-3433.

- Sarah J. Hawkins; Ronald R. Charpentier; Christopher J. Schenk; Heidi M. Leathers-Miller; Timothy R. Klett; Michael E. Brownfield; Tom M. Finn; Stephanie B. Gaswirth; Kristen R. Marra; Phuong A. Le; Tracey J. Mercier; Janet K. Pitman; Marilyn E. Tennyson (June 2016). "Assessment of Continuous (Unconventional) Oil and Gas Resources in the Late Cretaceous Mancos Shale of the Piceance Basin, Uinta-Piceance Province, Colorado and Utah, 2016" (PDF). pubs.usgs.gov. USGS. Retrieved June 10, 2018.

Using a geology-based assessment methodology, the U.S. Geological Survey assessed technically recoverable mean resources of 74 million barrels of shale oil, 66.3 trillion cubic feet of gas, and 45 million barrels of natural gas liquids in the Mancos Shale of the Piceance Basin in Colorado and Utah

- US Energy Information Administration: Top 100 oil and gas fields Archived 2009-05-15 at the Wayback Machine, Table B2, PDF file, retrieved 19 February 2009.

- "USGS updates Piceance basin oil shale assessments". Oil and Gas Journal. Pennwell Corporation. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- USGS Technical Announcement: U.S. Oil Shale Assessments Updated Released: 4/2/2009 10:14:35 AM Retrieved 17 June 2014

- Ted, Sickenger (March 11, 2016). "Feds reject Jordan Cove LNG terminal". The Oregonian. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- Sickenger, Ted (March 25, 2016). "Jordan Cove LNG finds potential gas buyer, says there is need for the project". The Oregonian. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

"Because the record does not support a finding that the public benefits of the Pacific Connector Pipeline outweigh the adverse effects on landowners, we deny Pacific Connector's request...to construct and operate the pipeline," the commission's order said.

- https://naturalresources.house.gov/calendar/eventsingle.aspx?EventID=404820 https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=177&v=YU4s6JqJCLY

- Lucas, Peter; Drexler, James (1976). Braunstein, Jules (ed.). Altamont-Bluebell - A Major, Naturally Fractured Stratigraphic Trap, Uinta Basin, Utah, in North American Oil and Gas Fields. Tulsa: The American Association of Petroleum Geologists. pp. 121–135. ISBN 978-0891813002.

- USGS Uinta-Piceance Assessment Team (2002). The Uinta-Piceance Province - Introduction to a Geologic Assessment of Undiscovered Oil and Gas Resources, USGS Digital Data Series DDS-69-B. USGS. ISBN 978-0-607-99359-2.

- US Geological Survey (Mar. 2009): Nahcolite Resources of the Green River Formation, Piceance Basin, Northwestern Colorado, Fact Sheet 2009-3011, PDF file, retrieved 5 April 2009.

- US Geological Survey (Mar. 2009): Assessment of In-Place Oil Shale Resources, Green River Formation, Piceance Basin, Western Colorado, Fact Sheet 2009-3012, PDF file, retrieved 5 April 2009.

- Ronald C. Johnson and others: An Assessment of In-Place Oil Shale Resource in the Green River Formation, Piceance Basin, Colorado, US Geological Survey, retrieved 5 April 2009.

- Thomas, Judith C. Overview of Groundwater Quality in the Piceance Basin, Western Colorado, 1946-2009, US Geological Survey, retrieved 16 August 2013.

External links

- "Piceance Creek Basin". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2013-12-24.