Photozincography of Domesday Book

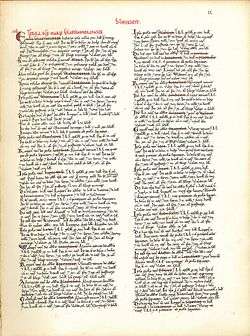

In the 1860s the first facsimile of Domesday Book was created by the process of photozincography (later termed zinco), and was executed under the directorship of Henry James at the Southampton offices of the Ordnance Survey.

Initial stages

Having developed the photozincographic process, in a meeting arranged between James and William Ewart Gladstone, then Chancellor of the Exchequer, Sir Henry expressed his ability to produce photozincographic copies of ancient documents at "a very trifling cost".[1] James outlined for his superiors the cost of a complete reproduction of Domesday Book (an estimate of £1575 for 500 copies or £3.3s per copy) using his process. In addition to this James further outlined the cost of a single county to demonstrate the affordability of the process, using Cornwall as an example of one of the shorter entries in the volumes (eleven folio pages) and estimated the cost of 500 copies to be £11. 2s. 4d. In doing so he selected the first extract of Domesday Book that he would photozincograph.

On 24 January 1861, Sir Henry was granted permission to photozincograph the Cornwall fragment of Domesday as a Treasury funded experiment to determine the success of the process. Joseph Burtt, one of the Assistant Keepers of the Records was directed to assist the Record Office binder, Hood, to unbind the relevant pages from Domesday and on Monday 4 February 1861 Burtt transported Domesday to Southampton by train.[2]

Domesday Book in Southampton

On arrival at the Ordnance Survey offices in Southampton, Burtt expressed his satisfaction with the buildings' "fireproof principles, and…military guard", and was given use of the best room in the building in which Domesday was placed in a fireproof safe, and the key entrusted to Burtt. Burtt’s description of the preparations extends to the actual photozincographic process, including James’s insistence that all plates should be developed and printed before the folios were returned. Nevertheless, the photozincography of Cornwall was completed in 11 days and Burtt returned to London.[3] The process was carried out in the Ordnance Survey photography building nicknamed the glasshouse.

Permissions and difficulties

Having completed Cornwall, James requested permission to photozincograph the rest of Domesday. Despite his claim that the public sale of the bound and engraved copies could cover the entire cost of the photozincography of the counties, the Lords of the Treasury wished to consult the Master of the Rolls regarding the comparison of James’s photozincographic reproductions with a rival process employed by Rev. Lambert Larking of Kent.[4] Larking (a local antiquarian) had employed an artist to assist the reproduction of the county of Kent using the lithographic process - a much more expensive means of reproduction than photozincography. However, in order to secure this permission over Larking's process James had to provide the Treasury with evidence of public interest and a guarantee of low-cost production. Thomas Letts of Letts Son & Co. Limited, London distributed a circular nationally bearing a foreword from James encouraging subscription, and by late October more than fifty subscribers to each county had been amassed. On 28 November 1861 Burtt returned to Southampton once more with Domesday for the aforementioned counties’ photozincographing, and by December James had secured permission from the Treasury to copy the remainder of Great Domesday – but he was explicitly forbidden from reproducing Kent, in defence of Larking’s lithograph. By 1864 the facsimile of the entirety of Great Domesday had been completed, and had been published in 32 county volumes including Kent following Larking's death, who granted James permission to complete the reproduction of the county due to his infirmity in the final stages of his life.[5]

The volumes were published in two colours (red and black), replicating the colours used in the original manuscript.

Today

"The books which were printed by James's method are still sought after even if they are not up to the standard of later facsimiles. His edition of Domesday Book is still the only facsimile of it available and can be found reasonably cheaply, whereas the letterpress is extremely rare and very expensive."

G. Wakeman, 1970.[6]

See also

References

- H. James, Domesday Book, or The Great Survey of England of William the Conqueror...Fac-Simile of the Part Relating to Cornwall, (Southampton: by H.M. Command, 1860), pp. 1-2

- E. Hallam, Domesday Book: Through Nine Centuries, (London: Guild Publishing, 1986), p. 154

- PRO 1/25 16 Feb. 1861

- E. Hallam, Domesday Book: Through Nine Centuries, (London: Guild Publishing, 1986), p. 155

- T. Owen & E. Pilbeam, Ordnance Survey: Map Makers to Britain since 1791, (Southampton: Ordnance Survey; London: H.M.S.O., 1992), p. 59

- G. Wakeman, Aspects of Victorian Lithography, (Wymondham: Brewhouse Press, 1970), p.58