Photography by indigenous peoples of the Americas

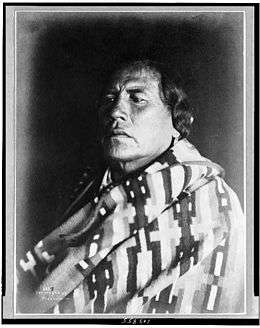

Photography by indigenous peoples of the Americas is an art form that began in the late 19th century and has expanded in the 21st century, including digital photography, underwater photography, and a wide range of alternative processes. Indigenous peoples of the Americas have used photography as a means of expressing their lives and communities from their own perspectives. Native photography stands in contrast to the ubiquitous photography of indigenous peoples by non-natives, which has often been criticized as being staged, exoticized, and romanticized.

1880s–1920s

Indigenous peoples of the Americas embraced photography in the 19th century. Some even owned and operated their own photography studios, such as Antonio Calderón Sandoval (Purépecha, ca. 1847–unknown), the grandfather of Frida Kahlo; Benjamin Haldane (1874–1941), Tsimshian of Metlakatla Village on Annette Island, Alaska;[1] and Richard Throssel (1882–1933), Cree of Montana. Max T. Vargas (father of pin-up artist Alberto Vargas), was a successful Mestizo photographer in Arequipa, Peru, who taught photography to Martín Chambi (Quechua, 1891–1973), an Indigenous miner. Jennie Ross Cobb (1881–1959), Cherokee Nation of Park Hill, Oklahoma, began developing her own film as a young child and photographed her college classmates, family, neighbors, and students.

The works of these early indigenous photographer stand in stark contrast to the romanticized images of non-native photographers. Recent scholarship by Mique’l Askren (Tsimshian-Tlingit) on the photographs of Benjamin A. Haldane has analyzed the functions that Haldane's photographs served for his community: as markers of success by having European-American-style formal portraits taken, and as markers of the continuity of potlaching and customary ceremonials by having photographs taken in ceremonial regalia. This second category is particularly significant because the use of the ceremonial regalia was against the law in Canada between 1885-1951.[2]

Native American boarding schools were important centers for photography at the turn of the century. John Leslie (Puyallup) learned photography at Carlisle Indian School. In 1895, Leslie published a book of his photography and exhibited his photographs at the 1895 Atlanta International Exposition[3][4] By 1906 Carlisle Indian School built a state-of-the-art photography studio and taught photography classes to its Native students.[4] Parker McKenzie (1897–1999) and his wife Nettie Odlety McKenzie (1896–1978) purchased cameras and took photographs while they attended Phoenix Indian School in 1916.

1920s–1940s

Peter Pitseolak (1902–1973), Inuk from Cape Dorset, Nunavut, documented Inuit life in the mid-20th century while dealing with challenges presented by the harsh climate and extreme light conditions of the Canadian Arctic. He developed his film himself in his igloo, and some of his photos were shot by oil lamps.

Horace Poolaw (1906–1984), Kiowa, shot over 2,000 images of his neighbors and relatives in Western Oklahoma from the 1920s onward.

Jean Fredericks (b. 1906), Hopi, had to carefully negotiate cultural views towards photography and made a point of not offering his portraits of Hopi people for sale to the public.[5]

1950s–1999

For a 1980s exhibit of Hopi photographers at Northlight Gallery in Tempe, Arizona, Victor Masayesva, Jr. (Hopi) explained how Hopis protect their privacy from the flood of photographs of them and their community by non-Hopi people. Hopi photographers know that certain subjects, especially ceremonial dances are not meant to be photographed. "The camera which is available to us is a weapon that will violate the silences and secrets so essential to our group survival," he wrote.[6] Many Hopi photographers do not sell their work to outsides.[7]

The establishment of tribal newspapers, such as the Qua Toqti and Hopi Tribal News both in the 1970s, created a demand for Native photojournalists.[8] Owen Seumptewa (Hopi) became photographic consultant to his tribe in 1976.[9]

While many native photographers were interested in documenting tribal life, Luis González Palma (Mestizo, b. 1957) borrows from a Victorian aesthetic to create haunting, mysterious portraits of Mayan and mestizo people, especially women, from his native Guatemala. He shoots in black and white but then hand-tints the photographs in sepia tones.[10]

The first Canadian national conference of indigenous photographers took place in March 1985 in Hamilton, Ontario, and from that the Native Indian/Inuit Photographers' Association (NIIPA) was formed.[11] During the 1980s, NIIPA had fifty members from North America.[12]

21st century

Today more Native people are professional art photographers; however, acceptance to the genre has met with challenges. Hulleah Tsinhnahjinnie (Navajo-Muscogee-Seminole), has not only established a successful career with her own work, she has also been an advocate for the entire field of Native American photography. She has curated shows and organized conferences at the C.N. Gorman Museum at UC Davis featuring Native American photographers. Tsinhnahjinnie wrote the book, Our People, Our Land, Our Images: International Indigenous Photographers. Larry McNeil (Tlingit) is a fine art photographer and professor who has mentored many emerging indigenous photographers. Together with Tsinhnahjinnie, McNeil curated New Native Photography at the New Mexico Museum of Art to draw more attention to the genre of photography during the 2011 Santa Fe Indian Market.[13]

Native photographers taking their skills into the fields of art videography, photocollage, digital photography, and digital art.

Notes

- Artwork in Our People, Our Land, Our Images. Archived 2008-08-29 at the Wayback Machine The Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture. Retrieved 1 Feb 2012.

- "Mique'l Askren, Bringing our History into Focus: Re-Developing the Work of B.A. Haldane, 19th Century Tsimshian Photographer, Blackflash: Seeing Red, Volume 24, No. 3, 2007, pp. 41-47". Archived from the original on March 6, 2012.

- Turner, Laura. "John Nicholas Choate and the Production of Photography at the Carlisle Indian School." Visualizing a Mission: Artifacts and Imagery of the Carlisle Indian School, 1879-1918. Retrieved 1 Feb 2012.

- Tsinhnahjinnie and Passalacqua xi

- Masayesva and Younger 42

- Masayesva and Younger 10

- Masayesva and Younger 33

- Masayesva and Younger 36

- Masayesva and Younger 37

- "Luis González Palma." Utata Tribal Photography. Retrieved 1 Feb 2012.

- "Native Indian/Inuit Phototgraphers' Association (NIIPA)." Connexions. 1986. Retrieved 6 Feb 2012.

- Weideman 36

- Weideman 36–7

References

- Masayesva, Victor and Erin Younger (1983). Hopi Photographers: Hopi Images. Sun Tracks, Tucson, Arizona. ISBN 978-0-8165-0804-4.

- Tsinhnahjinnie, Hulleah J. and Veronica Passalacqua, eds. Our People, Our Land, Our Images: International Indigenous Photography. Berkeley: Heyday Books, 2008. ISBN 978-1-59714-057-7.

- Weideman, Paul. "Hi-rez: New Native Photography, 2011." New Mexican: Pasatiempo. August 19–25, 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Indigenous photography of the Americas. |

- Our People, Our Land, Our Images, Museum of Nebraska Art

- Visual Sovereignty: International Indigenous Photography, C.N. Gorman Museum

- New Native Photography, New Mexico Museum of Art