Volt

The volt (symbol: V) is the derived unit for electric potential, electric potential difference (voltage), and electromotive force.[1] It is named after the Italian physicist Alessandro Volta (1745–1827).

| Volt | |

|---|---|

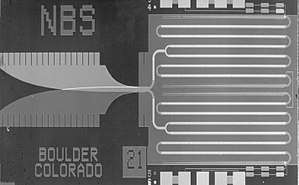

Josephson voltage standard chip developed by the National Bureau of Standards as a standard volt | |

| General information | |

| Unit system | SI derived unit |

| Unit of | Electric potential, electromotive force |

| Symbol | V |

| Named after | Alessandro Volta |

| In SI base units: | kg·m2·s−3·A−1 |

Definition

One volt is defined as the difference in electric potential between two points of a conducting wire when an electric current of one ampere dissipates one watt of power between those points.[2] Equivalently, it is the potential difference between two points that will impart one joule of energy per coulomb of charge that passes through it. It can be expressed in terms of SI base units (m, kg, s, and A) as:

It can also be expressed as amperes times ohms (current times resistance, Ohm's law), webers per second (magnetic flux per time), watts per ampere (power per unit current, definition of electric power), or joules per coulomb (energy per unit charge), which is also equivalent to electronvolts per elementary charge:

Josephson junction definition

The "conventional" volt, V90, defined in 1987 by the 18th General Conference on Weights and Measures[3] and in use from 1990, is implemented using the Josephson effect for exact frequency-to-voltage conversion, combined with the caesium frequency standard.

For the Josephson constant, KJ = 2e/h (where e is the elementary charge and h is the Planck constant), a "conventional" value KJ-90 = 0.4835979 GHz/μV was used for the purpose of defining the volt. As a consequence of the 2019 redefinition of SI base units, the Josephson constant was redefined in 2019 to have an exact value of KJ = 483597.84841698... GHz⋅V−1,[4] which replaced the conventional value KJ-90.

This standard is typically realized using a series-connected array of several thousand or tens of thousands of junctions, excited by microwave signals between 10 and 80 GHz (depending on the array design).[5] Empirically, several experiments have shown that the method is independent of device design, material, measurement setup, etc., and no correction terms are required in a practical implementation.[6]

Water-flow analogy

In the water-flow analogy, sometimes used to explain electric circuits by comparing them with water-filled pipes, voltage (difference in electric potential) is likened to difference in water pressure. Current is proportional to the diameter of the pipe or the amount of water flowing at that pressure. A resistor would be a reduced diameter somewhere in the piping and a capacitor/inductor could be likened to a "U" shaped pipe where a higher water level on one side could store energy temporarily.

The relationship between voltage and current is defined (in ohmic devices like resistors) by Ohm's law. Ohm's Law is analogous to the Hagen–Poiseuille equation, as both are linear models relating flux and potential in their respective systems.

Common voltages

The voltage produced by each electrochemical cell in a battery is determined by the chemistry of that cell (see Galvanic cell § Cell voltage). Cells can be combined in series for multiples of that voltage, or additional circuitry added to adjust the voltage to a different level. Mechanical generators can usually be constructed to any voltage in a range of feasibility.

Nominal voltages of familiar sources:

- Nerve cell resting potential: ~75 mV[7]

- Single-cell, rechargeable NiMH[8] or NiCd battery: 1.2 V

- Single-cell, non-rechargeable (e.g., AAA, AA, C and D cells): alkaline battery: 1.5 V;[9] zinc-carbon battery: 1.56 V if fresh and unused

- LiFePO4 rechargeable battery: 3.3 V

- Cobalt-based Lithium polymer rechargeable battery: 3.75 V (see Comparison of commercial battery types)

- Transistor-transistor logic/CMOS (TTL) power supply: 5 V

- USB: 5 V DC

- PP3 battery: 9 V

- Automobile battery systems are 2.1 volts per cell; a "12V" battery is 6 cells or 12.6V; a "24V" battery is 12 cells or 25.2V. Some antique vehicles use "6V" 3-cell batteries or 6.3 volts.

- Household mains electricity AC: (see List of countries with mains power plugs, voltages and frequencies)

- 100 V in Japan

- 120 V in North America,

- 230 V in Europe, Asia, Africa and Australia

- Rapid transit third rail: 600–750 V (see List of railway electrification systems)

- High-speed train overhead power lines: 25 kV at 50 Hz, but see the List of railway electrification systems and 25 kV at 60 Hz for exceptions.

- High-voltage electric power transmission lines: 110 kV and up (1.15 MV is the record; the highest active voltage is 1.10 MV[10])

- Lightning:, often around 100 MV.

History

In 1800, as the result of a professional disagreement over the galvanic response advocated by Luigi Galvani, Alessandro Volta developed the so-called voltaic pile, a forerunner of the battery, which produced a steady electric current. Volta had determined that the most effective pair of dissimilar metals to produce electricity was zinc and silver. In 1861, Latimer Clark and Sir Charles Bright coined the name "volt" for the unit of resistance.[11] By 1873, the British Association for the Advancement of Science had defined the volt, ohm, and farad.[12] In 1881, the International Electrical Congress, now the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC), approved the volt as the unit for electromotive force.[13] They made the volt equal to 108 cgs units of voltage, the cgs system at the time being the customary system of units in science. They chose such a ratio because the cgs unit of voltage is inconveniently small and one volt in this definition is approximately the emf of a Daniell cell, the standard source of voltage in the telegraph systems of the day.[14] At that time, the volt was defined as the potential difference [i.e., what is nowadays called the "voltage (difference)"] across a conductor when a current of one ampere dissipates one watt of power.

The "international volt" was defined in 1893 as 1/1.434 of the emf of a Clark cell. This definition was abandoned in 1908 in favor of a definition based on the international ohm and international ampere until the entire set of "reproducible units" was abandoned in 1948. [15]

A redefinition of SI base units, including defining the value of the elementary charge, took effect on 20th May 2019.[16]

See also

- Orders of magnitude (voltage)

- Rail traction voltage

- SI electromagnetism units

- SI prefix for unit prefixes

- Standardised railway voltages

- Voltmeter

References

- "SI Brochure, Table 3 (Section 2.2.2)". BIPM. 2006. Archived from the original on 2007-06-18. Retrieved 2007-07-29.

- BIPM SI Brochure: Appendix 1, p. 144

- "Resolutions of the CGPM: 18th meeting (12-15 October 1987)".

- "Mise en pratique for the definition of the ampere and other electric units in the SI" (PDF). BIPM.

- Burroughs, Charles J.; Bent, Samuel P.; Harvey, Todd E.; Hamilton, Clark A. (1999-06-01), "1 Volt DC Programmable Josephson Voltage Standard", IEEE Transactions on Applied Superconductivity, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), 9 (3): 4145–4149, Bibcode:1999ITAS....9.4145B, doi:10.1109/77.783938, ISSN 1051-8223

- Keller, Mark W (2008-01-18), "Current status of the quantum metrology triangle" (PDF), Metrologia, 45 (1): 102–109, Bibcode:2008Metro..45..102K, doi:10.1088/0026-1394/45/1/014, ISSN 0026-1394, archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-05-27, retrieved 2010-04-11,

Theoretically, there are no current predictions for any correction terms. Empirically, several experiments have shown that KJ and RK are independent of device design, material, measurement setup, etc. This demonstration of universality is consistent with the exactness of the relations, but does not prove it outright.

- Bullock, Orkand, and Grinnell, pp. 150–151; Junge, pp. 89–90; Schmidt-Nielsen, p. 484

- Hill, Paul Horowitz; Winfield; Winfield, Hill (2015). The Art of Electronics (3. ed.). Cambridge [u.a.]: Cambridge Univ. Press. p. 689. ISBN 978-0-521-809269.

- SK Loo and Keith Keller (Aug 2004). "Single-cell Battery Discharge Characteristics Using the TPS61070 Boost Converter" (PDF). Texas Instruments.

- "World's Biggest Ultra-High Voltage Line Powers Up Across China". www.bloomberg.com. 1 January 2019. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- As names for units of various electrical quantities, Bright and Clark suggested "ohma" for voltage, "farad" for charge, "galvat" for current, and "volt" for resistance. See:

- Latimer Clark and Sir Charles Bright (1861) "On the formation of standards of electrical quantity and resistance," Report of the Thirty-first Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science (Manchester, England: September 1861), section: Mathematics and Physics, pp. 37-38.

- Latimer Clark and Sir Charles Bright (November 9, 1861) "Measurement of electrical quantities and resistance," The Electrician, 1 (1) : 3–4.

- Sir W. Thomson, et al. (1873) "First report of the Committee for the Selection and Nomenclature of Dynamical and Electrical Units," Report of the 43rd Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science (Bradford, September 1873), pp. 222-225. From p. 223: "The "ohm," as represented by the original standard coil, is approximately 109 C.G.S. units of resistance ; the "volt" is approximately 108 C.G.S. units of electromotive force ; and the "farad" is approximately 1/109 of the C.G.S. unit of capacity."

- (Anon.) (September 24, 1881) "The Electrical Congress," The Electrician, 7 : 297.

- Hamer, Walter J. (January 15, 1965). Standard Cells: Their Construction, Maintenance, and Characteristics (PDF). National Bureau of Standards Monograph #84. US National Bureau of Standards.

- "Revised Values for Electrical Units" (PDF). Bell Laboratories Record. XXV (12): 441. December 1947.

- Draft Resolution A "On the revision of the International System of units (SI)" to be submitted to the CGPM at its 26th meeting (2018) (PDF)