Persistent Müllerian duct syndrome

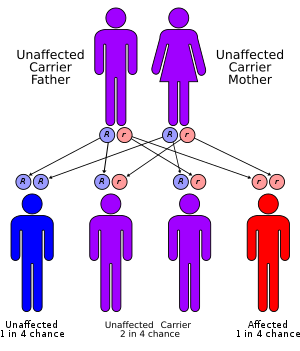

Persistent Müllerian duct syndrome (PMDS) is the presence of Müllerian duct derivatives (fallopian tubes, uterus, and/or the upper part of the vagina)[1] in what would be considered a genetically and otherwise physically normal male animal by typical human based standards.[2] In humans, PMDS typically is due to an autosomal recessive[3] congenital disorder and is considered by some to be a form of pseudohermaphroditism due to the presence of Müllerian derivatives.[1][4]

| Persistent Müllerian duct syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Persistent Müllerian derivatives |

| |

| Persistent Müllerian duct syndrome has an autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance. | |

| Specialty | Medical genetics |

Typical features include undescended testes (cryptorchidism) and the presence of a small, underdeveloped uterus in an XY infant or adult. This condition is usually caused by deficiency of fetal anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) effect due to mutations of the gene for AMH or the anti-Müllerian hormone receptor, but may also be as a result of insensitivity to AMH of the target organ.[1]

Symptoms

The first visible signs of PMDS after birth is Cryptorchidism (undescended testes) either unilaterally or bilaterally.[5] Along with Cryptorchidism, is also inguinal hernias which may be presented unilaterally (affects one testicle) or bilaterally (affects both testicles).[5] Adults who have been oblivious to this condition may be presented with haematuria, which is when blood appears in urine because of hormonal imbalances. PMDS Type I, is also referred to as ‘Hernia Uteri Inguinalis’, which exhibits one descended testis that has also pulled the fallopian tube and sometimes uterus, through the inguinal canal.[6] The descended testes, fallopian tube and uterus all fall in the same inguinal canal, causing an inguinal hernia.[6] Altogether when the aforementioned conditions occur, it is called ‘Transverse Testicular Ectopia’.[6]

Under the microscope, some samples taken for biopsies displayed results where testicular tissue was at a stage of immaturity, and showed dysplasia.[7]

Molecular genetics

Mutation in AMH gene (PMDS Type 1) or AMHR2 gene (PMDS Type 2) are the primary causes of PMDS.[8] AMH, or sometimes referred to as Müllerian Inhibiting Substance (MIS), is secreted by Sertoli cells during an individual's whole life.[6] It is essential during the foetal period as it functions to regress the Müllerian ducts. However, AMH also functions in the last trimester of pregnancy, after birth, and even during adulthood in minimal amounts.[6] The Sertoli cells in males secrete AMH, through the presence of a Y chromosome.[6]

The role of the AMH gene in reproductive development, is the production of a protein that contributes to male sex differentiation. During development of male foetuses, the AMH protein is secreted by cells within the testes. AMHs bind to the AMH Type 2 Receptors, which is present on cells on the surface of the Müllerian Duct. The binding of AMH to its receptors on the Müllerian duct induces the apoptosis of the Müllerian Duct cells, thus the regression of the Müllerian Duct within males.[9] However, for females who originally do not produce AMH proteins during foetal development, the Müllerian Duct eventually becomes the uterus and fallopian Tubes as normal.[9] With the AMH gene mutation (PMDS Type 1), the AMH is either not produced, produced in deficient amounts, defective, secreted at the wrong critical period for male differentiation or the Müllerian ducts manifested a resistance to AMH.[9]

AMHR2 contains the instructions for generating the receptors that AMH binds to. If there if a mutation in the AMHR2 gene, the response to AMH molecules binding to the receptor cannot be properly reciprocated. Other possibilities include an absence of the receptors, such that the AMH molecules cannot induce differentiation. Mutation in the AMHR2 is critical to proper male sex differentiation. The genetic mutational cause of PMDS, is a 27 base-pair deletion of the Anti-Mullerian Type 2 Receptor gene. The 27-base-pair deletion that occurs PMDS is in exon 10 on one allele.[7]

PMDS is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner.[8] The male individuals inherit mutated copies of the X-chromosomes from the maternal and paternal genes, implying the parents are carriers and do not show symptoms. Females inheriting two mutated genes do not display symptoms of PMDS, though remain as carriers. Males are affected genotypically with the karyotype (46, XY) and phenotypically.[10]

Diagnosis

Persistent Müllerian Duct Syndrome (PMDS), also known as Persistent Oviduct Syndrome, is a congenital disorder related to male sexual development. PMDS usually affects phenotypically normal male individuals with the karyotype (46, XY) and is a form of pseudohermaphroditism.[8][9] PMDS has various causes to do with AMH or receptors abnormalities. For example, AMH has failed to synthesis, failed to release or was secreted at the wrong time.[11] The condition develops in males that consist of normal functioning reproductive organs and gonads, but also female reproductive organs such as the uterus and fallopian tubes. The female reproductive organs origin from a structure from when both genders are still foetuses, called the “Mullerian Duct”. In males, the secretion of ‘Anti-Mullerian Hormone (AMH)’ causes the regression of the Müllerian Duct. Normally, both the Mullerian and Wolffian ducts are present during the 7th week of gestation. Approximately by the end of the 7th and beginning of the 8th week of gestation, the Sertoli cell's secretion of AMH occur, causing the male sex differentiation during foetal development.[9] The AMH molecules bind to AMHRII (Anti-Mullerian Hormone Receptor Type II) regressing the Müllerian duct. The Leydig cells secrete testosterone to aid male differentiation process by inducing structures such as the epididymis, vas deferens and seminal vesicles. However, with PMDS individuals, the Müllerian Duct persists instead of regressing, due to errors with AMH or the AMH receptor. The problem either coincides with the secretion of AMH (PMDS Type I) or the receptor (PMDS Type II).[12] PMDS is usually coincidentally found during surgery for inguinal hernia, or when the surgeon looks for the reason why the male individual is infertile in adulthood.[10]

Other diagnostic tests

Genetic

Another method for the confirmation of PMDS is Genetic Testing.[3] It is not usually preferred because of its processing period and cost. With image screenings such as ultrasounds and MRI, the condition can be efficiently confirmed. Genetic tests can identify those who hold the mutated gene, identify the family member's chances and risks, and advise those who are trying to get pregnant.[3] Genetic counselling and further genetic testing is offered to confirm the chances and risks of an individual's offspring obtaining the pair of mutated genes. Further research into the family tree and inheritance is possible as well.

ELISA

An ELISA test is a form of immunoassaying which is a technique consisting of enzymes to identify the presence of particular substances. For PMDS, ELISA tests can be used to determine the levels of AMH within the male individual's serum, this is only effective before the individual reaches puberty as it normally increases in this period.[6] The result for PMDS patients display low levels of AMH within the serum, and low levels of testosterone.[6]

Mechanism

AMH (Anti Müllerian Hormone) is produced by the primitive Sertoli cells as one of the earliest Sertoli cell products and induces regression of the Müllerian ducts. Fetal Müllerian ducts are only sensitive to AMH action around the 7th or 8th week of gestation, and Müllerian regression is completed by the end of the 9th week.[13] The AMH induced regression of the Müllerian duct occurs in cranio-caudal direction via apoptosis. The AMH receptors are on the Müllerian duct mesenchyme and transfer the apoptotic signal to the Müllerian epithelial cell, presumably via paracrine actors. The Wolffian ducts differentiate into epididymides, vasa deferentia and seminal vesicles under the influence of testosterone, produced by the fetal Leydig cells.[14]

Treatment

The main form of treatment is laparotomy, a modern and minimally invasive type of surgery. Laparotomy properly positions the testes within the scrotum (orchidopexy) and remove Mullerian structures being the uterus and fallopian tubes.[8] Occasionally they are unsalvageable if located high in the retroperitoneum. During this surgery, the uterus is usually removed and attempts made to dissect away Müllerian tissue from the vas deferens and epididymis to improve the chance of fertility. If the person has male gender identity himself and the testes cannot be retrieved, testosterone replacement will be usually necessary at puberty should the affected individual choose to pursue medical attention. Lately, laparoscopic hysterectomy is offered to patients as a solution to both improve the chances of fertility and to prevent the occurrences of neoplastic tissue formation.[4] The surgery is recommended to be performed when the individual is between one and two years old, but usually done when less than one years old.[8] Having a target age for surgery reduces the risks of damaging the vas deferens. The vas deferens is in close proximity to the Mullerian structures, sometimes lodged in the uterine wall.[10][8] Overall, the purpose of the treatment improves self-identification of an individual, hopefully prevent the increased risk of cancer, and to prevent possibilities of infertility if not already.

PMDS patients have the possibility of being infertile in the future if not promptly operated on. When the affected males are adults, those who are not attentive of the condition may find the presence of blood in their semen (hematospermia).[15] The Mullerian structures and cryptorchidism also can develop into cancer if ignored, or if there are remaining pieces of Mullerian structures left from past surgery.[15] If PMDS was found during adulthood, or if Mullerian structures had to be left behind due to risks in surgery, biopsies of the remaining Mullerian structures can be tested. Through pathohistological observation, the endometrial tissues atrophy, and fallopian tubes begin to congest showing signs of fibrosis.[15]

Epidemiology

PMDS it a relatively rare congenital disease. From current data, approximately 45% of the known cases are caused by mutations in the AMH gene, being a mutation on chromosome 19 (Type I PMDS).[10] Approximately, 40% of the known cases are AMHR2 mutations, on the AMH Receptor Type 2 gene, which is on chromosome 12 (Type 2 PMDS).[10] The remaining unknown 15% are referred to as ‘Idiopathic PMDS’.[10]

Case Studies

PMDS is usually overseen because of the external symptoms such as the cryptorchidism and inguinal hernias, being assumed to be the only complication. Especially before the 21st century, these conditions were hard to diagnose due differences in imaging capabilities to the present. For this reason, there are cases where the older population, or those in poorer countries find out later.

A case reported in 2013, exhibits a 50-year-old male with history of low testosterone levels, high cholesterol and the congenital absence of his right testis.[11] Imaging presented the patient with three cystic masses, with similar structures to a uterus and ovary, thus PMDS.[11] During operation, the surgeons found malignant degeneration of the Mullerian remnants which occurs to the body if PMDS is unnoticed for a long period of time.[11] The cause of the complication presented to the male patient is due mainly to the unidentified bilateral cryptorchidism since birth, as doctors at that time assumed the complication was just the “congenital absence of his right testis”.[11] Overlooking the symptoms of PDMS can cause permanent negative effects such as infertility and future malignancies as shown by the male patient.[11] The malignant degeneration of the Mullerian structures is supportive evidence for the male patient's infertility.

See also

- Intersex

- Sexual differentiation

- Cryptorchidism

- Anti-müllerian hormone

References

- Renu D, Rao BG, Ranganath K (February 2010). "Persistent mullerian duct syndrome". primary. The Indian Journal of Radiology & Imaging. 20 (1): 72–4. doi:10.4103/0971-3026.59761. PMC 2844757. PMID 20352001.

- Carlson NR (2013). Physiology of behavior. review (11th ed.). Boston: Pearson. p. 328. ISBN 978-0205239399.

- Imbeaud S, Belville C, Messika-Zeitoun L, Rey R, di Clemente N, Josso N, Picard JY (September 1996). "A 27 base-pair deletion of the anti-müllerian type II receptor gene is the most common cause of the persistent müllerian duct syndrome". primary. Human Molecular Genetics. 5 (9): 1269–77. doi:10.1093/hmg/5.9.1269. PMID 8872466.

- Colacurci N, Cardone A, De Franciscis P, Landolfi E, Venditto T, Sinisi AA (February 1997). "Laparoscopic hysterectomy in a case of male pseudohermaphroditism with persistent Müllerian duct derivatives". primary. Human Reproduction. 12 (2): 272–4. doi:10.1093/humrep/12.2.272. PMID 9070709.

- Vanikar AV, Nigam LA, Patel RD, Kanodia KV, Suthar KS, Thakkar UG (June 2016). "Persistent mullerian duct syndrome presenting as retractile testis with hypospadias: A rare entity". primary. World Journal of Clinical Cases. 4 (6): 151–4. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v4.i6.151. PMC 4909461. PMID 27326401.

- Josso N, Belville C, di Clemente N, Picard JY (2005-05-05). "AMH and AMH receptor defects in persistent Müllerian duct syndrome". review. Human Reproduction Update. 11 (4): 351–6. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmi014. PMID 15878900.

- Pappis C, Constantinides C, Chiotis D, Dacou-Voutetakis C (April 1979). "Persistent Müllerian duct structures in cryptorchid male infants: surgical dilemmas". primary. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 14 (2): 128–31. doi:10.1016/0022-3468(79)90002-2. PMID 37292.

- Fernandes ET, Hollabaugh RS, Young JA, Wilroy SR, Schriock EA (December 1990). "Persistent müllerian duct syndrome". primary. Urology. 36 (6): 516–8. doi:10.1016/0090-4295(90)80191-O. PMID 1978951.

- Agrawal AS, Kataria R (June 2015). "Persistent Müllerian Duct Syndrome (PMDS): a Rare Anomaly the General Surgeon Must Know About". review. The Indian Journal of Surgery. 77 (3): 217–21. doi:10.1007/s12262-013-1029-7. PMC 4522266. PMID 26246705.

- Sekhon V, Luthra M, Jevalikar G (January 2017). "Persistent Mullerian Duct Syndrome presenting as irreducible inguinal hernia – A surprise surgical finding!". primary. Journal of Pediatric Surgery Case Reports. 16: 34–36. doi:10.1016/j.epsc.2016.11.002.

- Prakash N, Khurana A, Narula B (2009-10-01). "Persistent Müllerian duct syndrome". primary. Indian Journal of Pathology & Microbiology. 52 (4): 546–8. doi:10.4103/0377-4929.56160. PMID 19805969.

- Al-Salem AH (2017). "Persistent Müllerian Duct Syndrome (PMDS)". An Illustrated Guide to Pediatric Urology. review. Cham: Springer International Publishing Springer. pp. 287–293. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-44182-5_10. ISBN 978-3-319-44181-8.

- Shamim M (August 2007). "Persistent Mullerian duct syndrome with transverse testicular ectopia presenting in an irreducible recurrent inguinal hernia". primary. JPMA. The Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association. 57 (8): 421–3. PMID 17902529.

- Rey R (February 2005). "Anti-Müllerian hormone in disorders of sex determination and differentiation". review. Arquivos Brasileiros de Endocrinologia e Metabologia. 49 (1): 26–36. doi:10.1590/s0004-27302005000100005. PMID 16544032.

- Gujar NN, Choudhari RK, Choudhari GR, Bagali NM, Mane HS, Awati JS, Balachandran V (December 2011). "Male form of persistent Mullerian duct syndrome type I (hernia uteri inguinalis) presenting as an obstructed inguinal hernia: a case report". primary. Journal of Medical Case Reports. 5 (1): 586. doi:10.1186/1752-1947-5-586. PMC 3259122. PMID 22185203.

Further reading

- Picard JY, Cate RL, Racine C, Josso N (2017). "The Persistent Müllerian Duct Syndrome: An Update Based Upon a Personal Experience of 157 Cases". review. Sexual Development : Genetics, Molecular Biology, Evolution, Endocrinology, Embryology, and Pathology of Sex Determination and Differentiation. 11 (3): 109–125. doi:10.1159/000475516. PMID 28528332.

- Da Aw L, Zain MM, Esteves SC, Humaidan P (2016). "Persistent Mullerian Duct Syndrome: a rare entity with a rare presentation in need of multidisciplinary management". review. International Brazilian Journal of Urology. 42 (6): 1237–1243. doi:10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2016.0225. PMC 5117982. PMID 27532119.

- Elias-Assad G, Elias M, Kanety H, Pressman A, Tenenbaum-Rakover Y (June 2016). "Persistent Müllerian Duct Syndrome Caused by a Novel Mutation of an Anti-MüIlerian Hormone Receptor Gene: Case Presentation and Literature Review". review. Pediatric Endocrinology Reviews. 13 (4): 731–40. PMID 27464416.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |