Yukatchu

Yukatchu (ユカッチュ, 良人), also known as Samuree (サムレー)[1], were the aristocracy of the Ryukyu Kingdom. The scholar-bureaucrats of classical Chinese studies living in Kumemura held the majority of government positions.

Ryukyuan Caste System

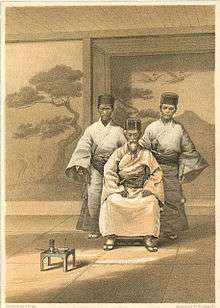

The Yukatchu were part of a complex caste system that existed in Ryukyu for centuries. They were the feudal scholar-officials class that was charged with enforcing the law and providing military defense to the nation, Ryukyu Kingdom. The specific rank of a Yukatchu was noted by the color of his hat.

Ryukyuan Caste System:

- Royalty – Shō family

- Oji (王子, Ōji): Prince

- Aji or Anji (按司, Aji): descendant of Prince, cadet branch of Royal House

- Yukatchu (良人, Yukatchu) – scholar-officials

-

- Pekumi (親雲上, Peekumii): upper Pechin

- Satunushi Pechin (里之子親雲上, Satunushi Peechin): middle Pechin

- Chikudun Pechin (筑登之親雲上, Chikudun Peechin): lower Pechin

- Satunushi (里之子, Satunushi): upper page

- Chikudun (筑登之, Chikudun): lower page

- Heimin (平民, Heimin) – commoners

The Yukatchu class was also responsible for the development of and training in the traditional fighting style, called Ti (Te), which developed into modern-day Karate. The Ryukyuan Yukatchu kept their fighting techniques secret, usually passing down the most devastating fighting forms to only one member of the family per generation, usually the eldest son.

| Status | Residence | Title | Rank | Jiifaa (hairpin) | Hachimachi (Hat) | Feudal Title and Estates | Household[2][3] | Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Royalty | Udun (御殿) |

Ōji | Mu-hon (Supreme) |

Gold | Golden Red Five-color | Aji-jitō (Magiri) |

Dēmyō | 2 | 0.002% | |

| Aji | Red Five-color Yellow Five-color |

26 | 0.032% | |||||||

| Upper Shizoku (Yukatchu) |

Tunchi (殿内) |

Uēkata | Shō-ippon (Senior First Rank) |

Purple Five-color Blue Five-color Purple |

Sō-jitō (Magiri) |

38 | 0.047% | |||

| Ju-ippon (Junior First Rank) |

Purple | |||||||||

| Shō-nipon (Senior Second Rank) | ||||||||||

| Ju-nipon (Junior Second Rank) |

Gold-silver | Waki-jitō (Village) |

296 | 0.367% | ||||||

| Peechin | Peekumii or Peechin |

Shō-sanpon (Senior Third Rank) |

Silver | Yellow | ||||||

| Ju-sanpon (Junior Third Rank) | ||||||||||

| Shō-yonpon (Senior Fourth Rank) | ||||||||||

| Ju-yonpon (Junior Fourth Rank) |

None | 20,759 | 25.79% | |||||||

| Shizoku (Yukatchu) |

Yaa (家) |

Satunushi Peechin Chikudun Peechin |

Shō-gohon (Senior Fifth Rank) | |||||||

| Ju-gohon (Junior Fifth Rank) | ||||||||||

| Shō-roppon (Senior Sixth Rank) | ||||||||||

| Ju-roppon (Junior Sixth Rank) | ||||||||||

| Shō-shichihon (Senior Seventh Rank) | ||||||||||

| Ju-shichihon (Junior Seventh Rank) | ||||||||||

| Satunushi | Shō-happon (Senior Eighth Rank) |

Red | ||||||||

| Ju-happon (Junior Eighth Rank) | ||||||||||

| Chikudun | Shō-kyūhon (Senior Ninth Rank) | |||||||||

| Ju-kyūhon (Junior Ninth Rank) | ||||||||||

| Shii (子) |

None | Copper | Blue / Green | |||||||

| Niya (仁屋) | ||||||||||

| Heimin | Hyakushō (百姓) |

None | Brass | None | None | 59,326 | 73.71% | |||

The Unarmed Ryukyuan scholar-officials

The first time that the Yukatchu's weapons were confiscated was during the reign of King Shō Shin (1477–1526), who centralized the Ryukyu Kingdom by forcing the Aji to leave their respective Magiri and move to Shuri. He confiscated weapons from commoners and Yukatchu who weren't part of the Ryukyuan military to lower the possibility of rebellion. The second time that the Yukatchu were disarmed was after the invasion of 1609 by Satsuma Domain, which prohibited the carrying of weapons by the Yukatchu.

The Yukatchu were not completely without weapons however. Historians in Okinawa have recovered documents that state that Satsuma outlawed the ownership and sale of firearms in Okinawa, but the Yukatchu class and above were allowed to keep firearms that were already in their family's possession.

Toshihiro Oshiro, historian and Okinawan martial arts master, states:

There is further documentation that in 1613 the Satsuma issued permits for the Ryukyu Samure to travel with their personal swords (tachi and wakizashi) to the smiths and polishers in Kagushima, Japan for maintenance and repair. From the issuance of these permits, it is logical to infer that there were restrictions on the Ryukyu Samure carrying their weapons in public, but it is also clear evidence that these weapons were not confiscated by the Satsuma.

Meiji Period

Undoubtedly the Yukatchu class was the hardest hit by the changing times. They were the only class that did not have a clear place in the modern world. In 1872, the Japanese Meiji government unilaterally proclaimed that the Ryukyu Kingdom was then Ryukyu Domain. In 1879, the Meiji government abolished the Ryukyu Domain and created Okinawa Prefecture, annexing the former kingdom.

- Public Proclamation by Chief Secretary Matsuda of Ryukyu Han

Because the Imperial Decree issued in Meiji 8th year (1875) has not been complied with, the Government was compelled to abolish the feudal clan. The former feudal Lord, his family and kin will be accorded princely treatment, and the persons of citizens, Ryūkyū Samure, their hereditary stipends, property and business interests will be dealt with in a manner as close to traditional customs as is possible. Any acts of maladministration, and exorbitant taxes and dues levied during the regime of the former clan government will probably be righted upon careful consideration. Do not be misled by irresponsible rumors. All are advised to pursue their respective occupations with ease of mind.

The hereditary lords of the Ryukyu Kingdom were strongly opposed to the complete annexation by Japan, but the Ryukyuan King forbade the Yukatchu from fighting the annexation. Ryukyu submitted to Japan's annexation plans and 300 lords, 2,000 aristocratic families and the king were removed from their positions of power. However, to avoid an armed revolt in Okinawa, as had happened in Japan, special ceremonies were performed for the Yukatchu class, where they were permitted to honorably accept defeat and ritually cut off their hair (top-knot).

In Okinawa the Yukatchu class lost a major source of income in 1903, when massive peasant protest sparked land reforms and the abolition of peasant taxes that sustained the Yukatchu. Many Yukatchu found themselves having to reveal their secret unarmed fighting techniques to commoners for income and to keep some element of status. Many Okinawan Karate styles list in their genealogy Karate masters of the Yukatchu class in the early stages of the style.

Martial arts

Warfare, law enforcement, and fighting systems were the primary business of the warrior class before the turn of the seventeenth century. Peasants, who often had to perform manual labor for eighteen hours a day to pay taxes to the upper classes and sustain themselves, did not have the energy, time or financial resources to practice the warrior arts. The warrior class, however, which was sustained by peasant taxes, could afford the luxury of sending the first born male child of a warrior family to be trained in Ti and other warrior arts.

Okinawan documents will often state that Ti or Kara-Ti was only practiced by the Yukatchu. However, there are early twentieth-century Japanese documents that mention this secret fighting style as being practiced by the peasants of Okinawa. The disconnect often comes from Japanese ignorance of the Ryukyuan caste system and at times seeing Okinawans as inferior Japanese. Though, around the time of the creation of the Okinawa Prefecture, some Yukatchu were calling themselves "Samure"; the word derives from the Japanese term "Samurai".

Shōshin Nagamine (recipient of the Fifth Class Order of the Rising Sun from the Emperor of Japan) states in his book The Essence of Okinawan Karate-Do, on pg. 21

- "The forbidden art (Kara-Te) was passed down from father to son among the samure class in Okinawa".

The Okinawa Prefectural Government in recent years has tried to clarify misunderstandings by the West as to the history and development of Karate in Okinawa. The Okinawa Prefectural Government English and Japanese website, Karate and martial arts with weaponry, states that Karate was a secret of the Yukatchu.

- Okinawan Te was practiced exclusively among the Ryūkyū or Okinawan feudal scholar-officials (Ryūkyū Samure) – Pechin. Peasants were strictly prohibited from practicing or being taught these secret unarmed fighting techniques.

History

At the beginning of the 17th century, around the time of the invasion of Ryukyu by the Japanese feudal domain of Satsuma, Kumemura and its community of Chinese scholars had deteriorated drastically; the royal government, along with that of Satsuma, then took action to revive it, and with it the aristocratic and intellectual culture of Ryukyu as a whole. The best and brightest of Ryukyu were invited to settle in Kumemura, pursue Chinese studies, and establish noble houses.

Thus, the yukatchu class was formally created around 1650, and divided into a number of ranks and titles from high to low: ueekata (親方), peekumi (親雲上), satunushi (里之子) and shii (子), each rank being accompanied by a rice stipend. These stipends were quite small as compared to those of Japanese samurai, but were likely quite appreciated, particularly after 1712, when the number of yukatchu increased dramatically, along with competition for positions in the bureaucracy; at this time, stipends were no longer guaranteed to those without government posts.

A yukatchu's primary purpose was to study traditional Chinese subjects; in addition to purely theoretic or academic studies, yukatchu of Kumemura were specifically cultivated for service in the royal bureaucracy, and in diplomatic relations with China. Though tribute missions to China were formally made once every two years, journeys between Ryukyu and Fujian were in fact much more frequent. An embassy was established in Fujian where yukatchu lived and studied; a small number would come and go every few years, so the individual residents at this trading post were constantly changing. In addition, a number of yukatchu would travel to Beijing for the formal tribute mission once every two years, and four Ryukyuan students were allowed to remain in Beijing's National Academy at any one time. In addition, many of the scholars sent to Fujian from Ryukyu were assigned to study a single, specific subject intensively, so as to become an expert, educating those at home in Ryukyu, and applying their new knowledge to administrative matters. Thus, the degree to which this entire class of people was supported by the government is far from insignificant, and serves as an important sign of the government's priorities and philosophy. In keeping good diplomatic and economic relations with China, the yukatchu acted not only to their own benefit and that of the Ryukyu royal government, but to the advantage of Satsuma and the Japanese central government, the Tokugawa shogunate. Dominated by Satsuma, Ryukyu served as an intermediary for Sino-Japanese commerce, though every effort was taken to ensure that Ryukyu's connections to Japan be kept secret from China. Thus, the yukatchu and the general focus on Chinese studies throughout the small kingdom was crucial not only for the direct political and economic reasons, but to attaining those ends through maintaining culturally Chinese appearances.

Towards the end of the 17th century, major reforms were encouraged by sessei (chief minister) Shō Shōken. By this point, the forced revival of the community pushed through decades earlier had been too successful, and had led to the creation of an aristocracy which led a fairly overindulgent, extravagant lifestyle, which had a noticeably negative effect on the overall prosperity and well-being of the kingdom. Shō Shōken thus encouraged the yukatchu, and elements of the royal government itself, to cut down on the extravagance of their festivals and ceremonies. Largely successful in immediate economic terms, the evolving nature of the aristocratic class was something much more difficult to control. By 1700 or so, thirty years after the end of Shō Shōken's time, the yukatchu had developed truly into an aristocratic class, defining themselves by birth, by their rankings, wealth, and family name, more so than by their education or intellect.

Sai On, a top government official from 1712 to the early 1750s, sought to return Ryukyu and the yukatchu to their proper cultural and intellectual path. He described in his autobiography incidents in which he, the son of a low-ranked yukatchu family, was ridiculed by higher-ranking aristocratic children, despite his superior education and talent. Among his many reforms, he created opportunities for yukatchu without government posts to earn a living as farmers or forestry managers. He also issued regulations for the yukatchu in 1730, banning prostitution, which blossomed at the time and disrupted the noble nature of the aristocratic class, and setting mandates regarding the status of illegitimate offspring.

There was opposition to Sai On's Confucian reforms, and political factions emerged among the yukatchu, those of Kumemura and those of Shuri (the capital) on opposite sides for the most part. One group of Shuri yukatchu, led by Heshikiya Chōbin, spoke out against the strict, repressive Confucian system of ethics, advocating a more natural, Buddhistic attitude, and exclaiming the importance of love and equality among all people.

The number of yukatchu increased dramatically again at the end of the 18th century, as families who contributed to the support of the impoverished government were accorded noble status in exchange. Perhaps one of the most damaging events for the stability and importance of the Kumemura yukatchu community was the establishment and gradual development of academies, and eventually a university, in Shuri. Though Kumemura had an institution of its own, the Meirindō, which trained diplomats for work in China, the unique purpose for which the yukatchu had been established nearly two centuries earlier was being challenged by the bureaucrats of Shuri; no longer was Kumemura the sole, or arguably even the primary, center of classical learning in Ryukyu. Ultimately, the kingdom did not remain independent long enough for this decline to reach its full potential.

When Ryukyu was formally annexed by Japan in 1879, Shigenori Uesugi,[4] the second appointed governor of the new territory, accused the yukatchu class as a whole of oppressing the Ryukyuan peasantry, and efforts were made to remove the nobles from power. For this reason, and others, many yukatchu fled to Fujian in China. The third governor, Michitoshi Iwamura, largely reversed this policy, supporting the maintenance of stipends for high-ranking yukatchu, retaining experienced bureaucrats in the administration of the prefecture, and lending economic aid to those without stipends. As a result, many yukatchu returned from China; stipends continued to be paid until 1909. Though Japanese policy was originally largely one of continuation of old traditions, by the turn of the 20th century, nationwide efforts to provide uniform education and create a uniform culture and language were implemented in Okinawa as they were throughout the nation.

The 1896 formation of the Kōdōkai ("Society for Public Unity") by former prince Shō En and a number of yukatchu, arguing against assimilation, can be said to be the final "gasp" of the yukatchu, twenty years after the abolition of the samurai class in "mainland" Japan.

Terminology

Samuree, a Ryukyuan pronunciation of the Japanese word "samurai", was often used interchangeably with yukatchu at the time, as both were aristocratic classes in their respective cultures. However, since the samurai were essentially warriors and the yukatchu scholars, the two terms do not truly share the same connotations. Similarly, Gregory Smits points out that while "noble" and "aristocrat" are commonly used to refer to yukatchu in English-language texts, these terms too have particular connotations based on their European origins which do not truly apply to the Ryukyuan case. The Aji constituted the true nobility.

References

- "ユカッチュ". 首里・那覇方言音声データベース (in Japanese).

- Ryukyu hanshin karoku-ki (琉球藩臣家禄記), National diet library, 1873

- Okinawa-ken tokei gaihyo (沖縄県統計概表), National diet library, 1876

- Note: all Japanese names after 1867 are presented in Western order, given name followed by family name.

- Smits, Gregory. (1999). "Visions of Ryukyu: Identity and Ideology in Early-Modern Thought and Politics." Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press.

- The Essence of Okinawan Karate-Do by Shosin Nagamine

- http://www.oshirodojo.com/kobudo_sai.html

- http://calmartialarts.com/karatearticle.shtml