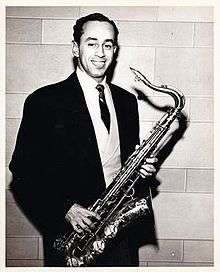

Paul Gonsalves

Paul Gonsalves (July 12, 1920 – May 15, 1974) was an American jazz tenor saxophonist[1] best known for his association with Duke Ellington. At the 1956 Newport Jazz Festival, Gonsalves played a 27-chorus solo in the middle of Ellington's "Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue,"[2] a performance credited with revitalizing Ellington's waning career in the 1950s.[3]

Paul Gonsalves | |

|---|---|

| |

| Background information | |

| Born | July 12, 1920 Brockton, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | May 15, 1974 (aged 53) London, England |

| Genres | Jazz, swing, bebop |

| Occupation(s) | Musician |

| Instruments | Tenor Saxophone |

| Years active | 1938–1974 |

| Labels | RCA Victor, Impulse!, Riviera, Black Lion |

| Associated acts | Phil Edmonds, Sabby Lewis, Count Basie, Dizzy Gillespie, Duke Ellington |

Biography

Born in Brockton, Massachusetts, to Cape Verdean parents, Gonsalves' first instrument was the guitar, and as a child he was regularly asked to play Cape Verdean folk songs for his family. He grew up in New Bedford, Massachusetts, and played as a member of the Sabby Lewis Orchestra. His first professional engagement in Boston was with the same group on tenor saxophone, in which he played before and after his military service during World War II.[4] Before joining Duke Ellington's orchestra in 1950, he also played in big bands led by Count Basie (1947–1949) and Dizzy Gillespie (1949–1950).

At the 1956 Newport Jazz Festival, Gonsalves' solo in Ellington's song "Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue" went through 27 choruses; the publicity from this performance is credited with reviving Ellington's career.[5] The performance is captured on the album Ellington at Newport. Gonsalves was a featured soloist in numerous Ellingtonian settings. He received the nickname "The Strolling Violins" from Ellington for playing solos while walking through the crowd.[6]

Gonsalves died in London a few days before Duke Ellington's death, after a lifetime of addiction to alcohol and narcotics.[7] Mercer Ellington refused to tell Duke of the passing of Gonsalves, fearing the shock might further accelerate his father's decline. Ellington and Gonsalves, along with trombonist Tyree Glenn, lay side by side in the same New York funeral home for a period of time.[8]

Gonsalves is buried at the Long Island National Cemetery in Farmingdale, New York.

On June 25, 2019, The New York Times Magazine listed Paul Gonsalves among hundreds of artists whose material was reportedly destroyed in the 2008 Universal fire.[9]

Discography

As leader/co-leader

- Cookin' (1957, Argo)

- Diminuendo, Crescendo and Blues (1958, RCA Victor)

- Ellingtonia Moods and Blues (1960, RCA Victor)

- Gettin' Together! (1961, Jazzland)

- Tenor Stuff (1961, Columbia) – with Harold Ashby

- Tell It the Way It Is! (1963, Impulse)

- Cleopatra – Feelin' Jazzy (1963, Impulse)

- Salt and Pepper (1963, Impulse) – with Sonny Stitt

- Rare Paul Gonsalves Sextet in Europe (1963, Jazz Connoisseur)

- Boom-Jackie-Boom-Chick (1964, Vocalion)

- Just Friends (1964, Columbia EMI) – with Tubby Hayes

- Change of Setting (1965, World Record Club) – with Tubby Hayes

- Jazz Till Midnight (1967, Storyville)

- Love Calls (1967, RCA) – with Eddie Lockjaw Davis

- Encuentro (1968, Fresh Sound)

- With the Swingers and the Four Bones (1969, Riviera)

- Humming Bird (1970, Deram)

- Just a-Sittin' and a-Rockin' (1970, Black Lion)

- Paul Gonsalves and His All Stars (1970, Riviera)

- Paul Gonsalves Meets Earl Hines (1970, Black Lion)

- Mexican Bandit Meets Pittsburgh Pirate (1973, Fantasy)

- Paul Gonsalves Paul Quinichette (1974)

- Sitting In (Paul Gonsalves and Clyde Fats Wright) (2014, Silk City)

As sideman

With Duke Ellington

- Ellington at Newport (Columbia, 1956)

- All Star Road Band (Doctor Jazz, 1957 [1983])

- All Star Road Band Volume 2 (Doctor Jazz, 1964 [1985])

- Hot Summer Dance (Red Baron, 1960 [1991])

- Love Calls (RCA Victor, 1968)

With Johnny Hodges

- Ellingtonia '56 (Norgran, 1956)

- The Big Sound (Verve, 1957)

- Triple Play (RCA Victor, 1967)

With John Lewis

- The Wonderful World of Jazz (Atlantic, 1960)

With Billy Taylor

- Taylor Made Jazz (Argo, 1959)

With Clark Terry

- Duke with a Difference (Riverside, 1957)

- Diminuendo, Crescendo And Blues (RCA Victor, 1958)

With Jimmy Woode

- The Colorful Strings of Jimmy Woode (Argo, 1957)

- With Joya Sherrill

- Joya Sherrill Sings Duke (20th Century Fox, 1965)

References

- "Paul Gonsalves", Allaboutjazz.com. Archived September 15, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- Allmusic biography

- Larson, Thomas E. The History and Tradition of Jazz, p. 106. Google Books.

- Carr, Ian and Digby Fairweather, Brian PriestleyThe Rough Guide to Jazz. Google Books.

- Martin, Henry and Keith Waters Jazz: the first 100 years, Cengage Learning, p. 150. Google Books.

- "Paul Gonsalves, Ellington band saxophonist," May 18, 1974. St. Petersburg Times

- Downbeat magazine, March 16, 1961, page 11, reports "Ellingtonians arrested in Vegas" "Ray Nance, Willie Cook. Andrew (Fats) Ford as well as Paul Gonsalves...the sheriff's squad seized...heroin plus hypodermic needles, eye droppers and other paraphernalia of the narcotic user"

- Hasse, John Edward Beyond Category: The Life and Genius of Duke Ellington, Da Capo Press, p. 385. Google Books.

- Rosen, Jody (June 25, 2019). "Here Are Hundreds More Artists Whose Tapes Were Destroyed in the UMG Fire". The New York Times. Retrieved June 28, 2019.

External links

- Paul Gonsalves discography at Discogs