Parkfield, California

Parkfield (formerly Russelsville)[2] is an unincorporated community in Monterey County, California.[1] It is located on Little Cholame Creek 21 miles (34 km) east of Bradley,[2] at an elevation of 1,529 feet (466 m).[1] As of 2007 road signs announce the population as 18.

Parkfield | |

|---|---|

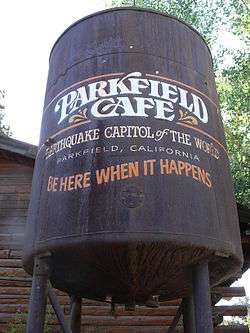

Parkfield Cafe | |

Parkfield Location in California  Parkfield Parkfield (the United States) | |

| Coordinates: 35°53′59″N 120°25′58″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| County | Monterey County |

| Elevation | 1,529 ft (466 m) |

Parkfield is located at 35°53′59″N 120°25′58″W[1] in the Temblor Range between the San Joaquin Valley and the Central Coast, at an elevation of 1,529 feet (466 m) above sea level. Mining and Homesteading used to be a prosperous activity in this community, but the mines were exhausted below economical recovery levels and the industry moved elsewhere. Today, it is a small town of about 18 people, most of whom are ranchers and farmers. There is a small tourism industry in the town based on equine-related events, hunting, a bluegrass music festival, and Parkfield's unique earthquake history (see the geology section below). The Parkfield motto is, "Be here when it happens."

A post office operated at Parkfield from 1884 to 1954.[2] The town's original name of Russelsville was rejected by the post office and Parkfield was chosen from the town's park-like setting among oak trees.[2]

The ZIP Code is 93451, and the community is inside area code 805.

Geology

Parkfield lies along the San Andreas Fault, one of the longest and most active faults in the United States, which appears in the town as a seasonally dry creek bed. The fault marks the divide between the North American Plate and the Pacific Plate (see plate tectonics). There is a bridge across the creek with piers on either side that have shifted more than five feet relative to one another due to aseismic creep since the bridge was constructed in 1936.[3] Google satellite images show that the bridge, which Simon Winchester described as "bent" and having cracked and patched pavement, has been replaced since Winchester's book was published, and a sliding joint installed; however, the west piers of the bridge remain displaced to the north. The bridge sports signage announcing to drivers that they are crossing the plate boundary.

Since at least 1857, Parkfield has experienced a magnitude 6 or greater earthquake about every 22 years.[4] In 1985, the US Geological Survey predicted that there would be a comparably-sized earthquake in this community by 1993, but no such event came until September 28, 2004, when a 6.0 Mw earthquake struck at 10:15 am Pacific Daylight Time.[5]

Parkfield is the most closely observed earthquake zone in the world. Scientists constantly measure the strain in rocks, heat flow, microseismicity, and geomagnetism around Parkfield. The observations of the San Andreas fault in Parkfield are hoped to help scientists better understand the physics of earthquakes and faulting; information gathered from Parkfield may still be used someday to issue predictions for major earthquakes along the San Andreas fault and around the world.

Since 1985, the United States Geological Survey has been working on a project known as "The Parkfield Experiment", a long-term research project on the San Andreas fault. "The experiment's purpose is to better understand the physics of earthquakes — what actually happens on the fault and in the surrounding region before, during and after an earthquake."

In 2004, work began just north of Parkfield on the San Andreas Fault Observatory at Depth (SAFOD). The goal of SAFOD is to drill a hole nearly 2.5 miles (4 kilometers) into the Earth's crust, across the San Andreas Fault. The specific target of the probe was a patch of fault known to generate sequences of repeating microearthquakes of around magnitude 1.0. The drilling was completed in the midyear of 2005, and an array of sensors was installed to capture and record earthquakes that happen near this area. It is hoped that SAFOD observations will provide insight into the source mechanisms of these small earthquakes, which can be scaled up in an effort to understand larger events. The drilling discovered a mineral called serpentinite at the site of origin of 2004 earthquake. Serpentinite can transform into talc, a very soft mineral, thus facilitating easy slippage of plates. It has been hypothesized that aseismic creep at Hollister is also due to the presence of serpentinite. No drilling has been done at Hollister to confirm this.

Notable Sights

Demonstration Aseismic creep near the town's main inn.

Demonstration Aseismic creep near the town's main inn. Tribute to the memory of Yokuts and other early settlers who lived in the Cholame area.

Tribute to the memory of Yokuts and other early settlers who lived in the Cholame area. Water fountain constructed from old oil well drilling parts, located in the town's park.

Water fountain constructed from old oil well drilling parts, located in the town's park.

Notes

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Parkfield, California

- Durham, David L. (1998). California's Geographic Names: A Gazetteer of Historic and Modern Names of the State. Clovis, Calif.: Word Dancer Press. p. 934. ISBN 1-884995-14-4.

- Simon Winchester, A Crack at the Edge of the World, Harper Collins, 2005; p. 162

- SeeMonterey: Parkfield

- USGS. "M6.0 - 18km N of Shandon, California". United States Geological Survey.