Parc des Buttes Chaumont

The Parc des Buttes Chaumont (pronounced [paʁk de byt ʃomɔ̃]) is a public park situated in northeastern Paris, France, in the 19th arrondissement. Occupying 24.7 hectares (61 acres), it is the fifth-largest park in Paris, after the Bois de Vincennes, Bois de Boulogne, Parc de la Villette and Tuileries Garden.

| Parc des Buttes Chaumont | |

|---|---|

Passerelle suspendue | |

| |

| Type | Urban park |

| Location | 19th arrondissement, Paris |

| Coordinates | 48°52′49″N 2°22′58″E |

| Area | 61 acres (25 ha) |

| Created | 1 April 1867 |

| Operated by | Direction des Espaces Verts et de l'Environnement (DEVE) |

| Status | Open all year |

| Public transit access | Located near the Métro stations: Buttes Chaumont, Laumière and Botzaris |

Opened in 1867, late in the regime of Napoleon III, it was built according to plans by Jean-Charles Adolphe Alphand, who created all the major parks demanded by the Emperor.[1] The park has 5.5 kilometres (3.4 miles) of roads and 2.2 kilometres (1.4 miles) of paths. The most famous feature of the park is the Temple de la Sibylle, inspired by the Temple of Vesta in Tivoli, Italy, and perched at the top of a cliff fifty metres above the waters of the artificial lake.[2]

History

The park took its name from the bleak hill which occupied the site, which, because of the chemical composition of its soil, was almost bare of vegetation – it was called Chauve-mont, or bare hill. The area, just outside the limits of Paris until the mid-19th century, had a sinister reputation; it was the site of the Gibbet of Montfaucon, the notorious place where from the 13th century until 1760, the bodies of hanged criminals were displayed after their executions.[3] After the 1789 Revolution, it became a refuse dump, and then a place for cutting up horse carcasses and a depository for sewage. The director of public works of Paris and builder of the Park, Jean-Charles Adolphe Alphand, reported that "the site spread infectious emanations not only to the neighboring areas, but, following the direction of the wind, over the entire city."[4]

Another part of the site was a former gypsum and limestone quarry mined for the construction of buildings in Paris and in the United States. This raw material was used for a long time to produce plaster and lime. In order to make lime, gypsum was heated in furnaces. This activity was maintained until the second half of the 19th century. By the end of the 1850s, the quarry was exhausted.[5] That quarry also yielded Eocene mammal fossils, including Palaeotherium, which were studied by Georges Cuvier. This not-very-promising site was chosen by Baron Haussmann, the Prefet of Paris, for the site of a new public park for the recreation and pleasure of the rapidly growing population of the new 19th and 20th arrondissements of Paris, which had been annexed to the city in 1860.

The work on the park began in 1864, under the direction of Alphand, who used all the experience and lessons he had learned in making the Bois de Boulogne and the Bois de Vincennes. Two years were required simply to terrace the land. Then a railroad track was laid to bring in cars carrying two hundred thousand cubic meters of topsoil. A thousand workers remade the landscape, digging a lake and shaping the lawns and hillsides. Explosives were used to sculpt the buttes themselves and the former quarry into a picturesque mountain fifty meters high with cliffs, an interior grotto, pinnacles and arches. Hydraulic pumps were installed to lift the water from the canal of the Ourcq River up the highest point on the promontory, to create a dramatic waterfall.

The quarries which occupied part of the site (1864)

The quarries which occupied part of the site (1864) The park under construction (1864–1867)

The park under construction (1864–1867) Map of the park at the time of its opening in 1867

Map of the park at the time of its opening in 1867 The park when it opened in 1867

The park when it opened in 1867 The Belvedere island in 1890–1900

The Belvedere island in 1890–1900 S.F. Électrographie turn-of-the-century photography

S.F. Électrographie turn-of-the-century photography

The chief gardener of Paris, horticulturist Jean-Pierre Barillet-Deschamps, then went to work, planting thousands of trees, shrubs and flowers, along with creating sloping lawns. At the same time, the city's chief architect, Gabriel Davioud, designed the miniature Roman temple on the top of the promontory, modeled after that at Tivoli near Rome, as well as belvederes, restaurants modeled after Swiss chalets, and gatehouses like rustic cottages, completing the imaginary landscape. The park opened on 1 April 1867, coinciding with the opening of the Paris Universal Exposition, and becoming an instant popular success with the Parisians.[6]

A view of the park and the Temple de la Sibylle

A view of the park and the Temple de la Sibylle The park on a sunny afternoon

The park on a sunny afternoon Cherry trees

Cherry trees The main promenade within the park

The main promenade within the park A pathway through the park

A pathway through the park The sloping lawns, a popular gathering place on weekends

The sloping lawns, a popular gathering place on weekends Temple Sybille from the lake shore

Temple Sybille from the lake shore A scene within the park

A scene within the park

Features of the park

The lake and the Île du Belvédère

The heart of the park is an artificial lake of 1.5 hectares (3.7 acres) surrounding the Île de la Belvédère, a rocky island with steep cliffs made from the old gypsum quarry. On the top is the Temple de la Sibylle, fifty meters above the lake. The island is connected by two bridges with the rest of the park. the island is surrounded by paths, and a steep stairway of 173 steps leads from the top of the belvedere down through the grotto to the edge of the lake.

The temple on the summit of the Île de la Belvédère.

The temple on the summit of the Île de la Belvédère. The artificial lake seen from the top of the island.

The artificial lake seen from the top of the island. A cement bridge on the path around the island.

A cement bridge on the path around the island.

The Temple de la Sibylle

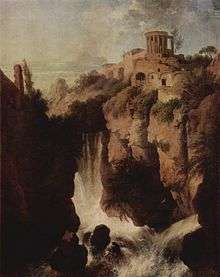

The most famous feature of the park is the Temple de la Sibylle, a miniature version of the famous ancient Roman Temple of Vesta in Tivoli, Italy. The original temple was the subject of many romantic landscape paintings from the 17th to the 19th century, and inspired similar architectural follies in the English landscape garden of the 18th century. The temple was designed by Gabriel Davioud, the city architect for Paris, who designed picturesque monuments for the Bois de Boulogne, Bois de Vincennes, Parc Monceau, and other city parks. He also designed some of the most famous fountains of Paris, including the Fontaine Saint-Michel. The temple was finished in 1867.

The Temple of Vesta in Tivoli, Italy was the subject of many romantic landscape paintings in the 18th and 19th centuries. This one is by Christian Dietrich, from about 1750.

The Temple of Vesta in Tivoli, Italy was the subject of many romantic landscape paintings in the 18th and 19th centuries. This one is by Christian Dietrich, from about 1750. Davioud's design for the temple in the park

Davioud's design for the temple in the park Davioud's Temple de la Sibylle (1867)

Davioud's Temple de la Sibylle (1867)

The grotto and waterfalls

The grotto is a vestige of the old gypsum and limestone quarry that occupied part of the site, now adjacent to rue Botzaris on the south side of the park. It is fourteen meters wide and twenty meters high, and has been sculpted and decorated with artificial stalactites as long as eight meters to make it resemble a natural grotto, in the style of the romantic English landscape garden of the 18th and 19th century. An artificial waterfall, fed by pumps, cascades from the top of the cave and down through the grotto to the lake.

A gallery of the former quarry has been transformed into a grotto with a 20-meter high artificial waterfall.

A gallery of the former quarry has been transformed into a grotto with a 20-meter high artificial waterfall. The cascade within the artificial grotto

The cascade within the artificial grotto The petite cascade, a small artificial waterfall

The petite cascade, a small artificial waterfall

The bridges

A 63-meter-long suspension bridge, eight meters above the lake, allows access to the belvedere. The bridge was designed by Gustave Eiffel, the creator of the Eiffel Tower.[7]

A 12-metre (39 ft) masonry bridge, 22 metres (72 ft) above the lake, known as the "suicide bridge", allows access to the belvedere from the south side of the park. After a series of well-publicized suicides, the bridge is now fenced with wire mesh.

A 63-meter long suspension bridge, designed by Gustave Eiffel in 1867, allows access to the island in the lake.

A 63-meter long suspension bridge, designed by Gustave Eiffel in 1867, allows access to the island in the lake. The so-called suicide bridge, 22 meters high, gives access to the island from the south side of the park.

The so-called suicide bridge, 22 meters high, gives access to the island from the south side of the park.

Architecture

Most of the architecture of the park, from the Temple de la Sibylle, the cafes, and gatehouses to the fences and rain shelters, was designed by Gabriel Davioud, chief architect for the city of Paris. He created a picturesque, rustic style for the parks of Paris, sometimes inspired by ancient Rome, sometimes by the chalets and bridges of the Swiss Alps.

A rain shelter, made of concrete hand sculpted to look like wood in a technique known as "faux bois"

A rain shelter, made of concrete hand sculpted to look like wood in a technique known as "faux bois" Davioud's paths on the Belvedere feature handrails made of hand-crafted concrete "faux bois".

Davioud's paths on the Belvedere feature handrails made of hand-crafted concrete "faux bois".

The main entrance to the park is at Place Armand-Carrel, where stands the mairie (town hall) of the 19th arrondissement, also designed by Davioud. There are five other large gates to the park — Porte Bolivar, Porte de la Villette, Porte Secrétan, Porte de Crimée, and Porte Fessart — and seven smaller gates.

As of 2019, the park hosts three restaurants (Pavillon du Lac, Pavillon Puebla, and Rosa Bonheur), two reception halls, two Guignol theatres, and two waffle stands. The two Guignol theatres were established in 1892.

The park has four Wi-fi zones as part of a citywide wireless Internet-access plan.

Flora

The park was envisioned by Napoleon III as a garden showcase, a vision that continue to guide the park's direction. Currently, there are more than 47 species of plants, trees, and shrubs cultivated in the park. Many of the plants and trees found in the park were those originally planted when the park was created.

The park boasts many varieties of indigenous and exotic trees (many of which are Asian species): in particular, several cedars of Lebanon planted in 1880, Himalayan cedars, Ginkgo Biloba, Byzantine hazelnuts, Siberian elms, European hollies, and bamboo-leafed prickly ashes, among many others.

Tree species found in the park include:

- Oriental Plane

- Hackberry

- Ornamental Pears

- Ginkgos

- Common Alder

- European Beech

- Giant Sequoia

- European Black Pine

- Large-leaved Linden

- Tulip Tree

Culture

In September, the park hosts Paris's annual Silhouette Short Film Festival. The Silhouette Festival features seven days of French and international short films, followed by an awards ceremony.

In 2008, a modern version of the traditional Guinguette, Rosa Bonheur, was established inside the park. This unique restaurant and dance venue is government-sponsored by the Mairie of the 19th arrondissement.

References

- Jarrassé, Dominique (2007). Grammaire des jardins Parisiens (in French). Parigramme. ISBN 978-2-84096-476-6.

- Centre des monuments nationaux (2002). Le guide du patrimoine en France (in French). Éditions du patrimoine. ISBN 978-2-85822-760-0.

- de Moncan, Patrice (2007). Les jardins du Baron Haussmann (in French). Les Éditions du Mécène. ISBN 978-2-907970-914.

- Downie, David (2005). "Montsouris and Buttes-Chaumont: the art of the faux". Paris, Paris: Journey into the City of Light. Fort Bragg: Transatlantic Press. pp. 34–41. ISBN 0-9769251-0-9.

- Fierro, Alfred (1999). "Buttes-Chaumont". Life and History of the 19th Arrondissement. Paris: Editions Hervas. pp. 80–100. ISBN 2-903118-29-9.

- Strohmayer, Ulf. "Urban Design and Civic Spaces: Nature at the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont in Paris. Cultural Geographies, 2006, 13, 4, 557-576".

- The Trees of Park Buttes Chaumont. Paris: Direction des Espaces Verts et de l'Environment. 2005. pp. 3–4.

- Tate, Alan (2001). "Parc des Buttes Chaumont, Paris". Great City Parks. London: Spon Press. pp. 47–59. ISBN 0-419-24420-4.

- Hedi Slimane (2002). Interview for Index Magazine.[8]

Notes and citations

- Dominique Jarrassé, Grammaire des jardins Parisiens, pg. 122

- De Moncan, Patrice, Les Jardins du Baron Haussmann, citing Edouard André, Les Jardins de Paris.

- Patrice de Moncan, Paris - Les Jardins du Baron Haussmann, p. 101.

- Alphand, Les Promenades de Paris. Cited in Patrice de Moncan.

- "Parc des Buttes Chaumont facts". Retrieved September 1, 2018.

- Patrice de Moncan, Paris - Les Jardins du Baron Haussmann, pp. 101-106.

- Structurae list of important works of civil engineering

- "Index Magazine". www.indexmagazine.com. Retrieved 2018-07-16.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Parc des Buttes-Chaumont. |

- Paris Office of Tourism: Parc des Buttes Chaumont (in English)

- Les Parc des Buttes Chaumont – current photographs and of the years 1900 (in English)

- High Resolution Travel Photographs of Parc des Buttes Chaumont – current high resolution photographs (in English)

- Theatre Guignol Anatole official site (in French)

- Le Guignol de Paris (in French)

- Parc des Buttes Chaumont (in English)

- Rosa Bonheur – website of the restaurant in the park