Paraburnetia

Paraburnetia is an extinct genus of biarmosuchian therapsids from the Late Permian of South Africa. It is known for its species P. sneeubergensis and belongs to the family Burnetiidae.[1] Paraburnetia lived just after the Permian–Triassic mass extinction event.

| Paraburnetia Temporal range: Late Permian | |

|---|---|

| |

| Life restoration of Paraburnetia sneeubergensis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Therapsida |

| Suborder: | †Biarmosuchia |

| Family: | †Burnetiidae |

| Genus: | †Paraburnetia Smith et al., 2006 |

| Species: | †P. sneeubergensis |

| Binomial name | |

| †Paraburnetia sneeubergensis Smith et al., 2006 | |

The etymology of Paraburnetia sneeubergensis comes from para, meaning beside or near; Burnetia indicating the first named member of the clade; and sneeubergensis for the location the Sneeuberge mountains above where the specimen was found.[1]

P. sneeubergensis is known by its knobby skull,[1] which is a shared synapomorphy with B. mirabilis[2] and P. viatkensis[3] They are synapsids, from which, their clade of therapsids is derived from.[4] Descending from one of the first therapsids, biarmosuchus, Paraburnetia evolved prominent canine teeth, a long zygomatic process that extends under the orbit, and shorter phalanges with fewer joints that the lizard-like pelycosaurs.[4] They were small to medium in sized carnivores.[4] Burnetiamorphs distinguished themselves from the basal forms of Biarmosuchians by developing bumpy knobs on their skulls, specifically towards the posterior of the skull and on the nasal.[4]

History and discovery

Paraburnetia was first discovered by a team from the South African Museum working in the southern Karoo Basin during July 2000. The specimen had been separated into two large portions. The first of which was originally identified due to the 'knob' on the synapsid skull. The snout was found downstream in the lower Beau-fort Group. The fitting of these two portions created the most complete skull of a burnetiid therapsid to date [5] .

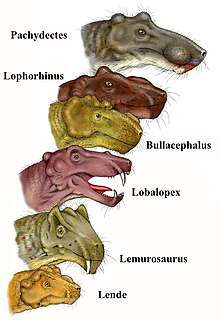

Previous burnetiids found were Burnetia mirabilis [2] from South Africa and Proburnetia viatkensis [6] from Russia. Historically, burnetiamorphs were difficult to place due to sharing characteristics with dinocephalians and gorgonopsians. [4] More recently, a series of taxa have been added to the group and its systematics have become better codified. Burnetiamorpha currently encompasses six genera: Bullacephalus, Burnetia, Lemurosaurus, Lobalopex, Niuksenitia, and Proburnetia[7][8]

Description

Paraburnetia is diagnosed by the characteristics of a superior temporal bulbous vertical horn, an upper orbital boss with a defined apical crest, and an elongated palatine-pterygoid boss.[1] Paraburnetia and Proburnetia share features indicating a sister-taxon relationship, including the presence of a well-developed median nasal crest and tall superior orbital bosses [1]

Distinctive characteristics that characterize it as a Burnetiamorph are its: "triangular supraorbital bosses; ridgelike nasal and frontal crests; bosses on the suborbital bar;swollen knob on the squamosal lateral to the quadrate;small incisors; and thickened rim along the posterior margin of the squamosal".[9]

Skull

In dorsal view, size of the skull is more similar to those of Bullacephalus, Burnetia, and Proburnetia, than the slightly smaller skull size of Lemurosaurus or Lobalopex.[1] The skull roof is triangular in dorsal view, with the width of the skull roof being narrower than its length.[1] The specimen's skull measures a length of 175 mm. [1] Additionally, the skull appears higher than the skull of Burnetia or Lobalopexdue due to the level of its preservation lacking dorsalventral compression.[1]

As shared by many basal therapsids (e.g., dinocephalians, anomodonts), the maxilla in Paraburnetia contacts the prefrontal.[1] In Paraburnetia, the maxilla stretches posterioraly and extends to meet the squamosal.[1] This is different from the situation reported by for Proburnetia, sister taxa to Paraburnetia,[10] where the maxilla was not considered to extend as far posteriorly.[1] There are four postcaniniforms in the left maxilla and five postcaniniforms in the right maxilla.[1] This differs from the seven postcaniniforms that probernetia have. [1] The premaxilla, that make up the tip of the snout, is relatively short and has five small teeth.[1] Additionally, the nasal dorsal surface is a thickened, median boss.[1] This is similarly present in Proburnetia, but more pronounced.[1] All burnetiamorphs except Lemurosaurus possess a median nasal boss.[1] In dorsal view, the frontal crest is prominent in Paraburnetia more so than in Proburnetia.[1] It flattens and broadens until it reaches the interorbital region.[1] The squamosal appears thickened along the posterior border with the tabular.[9]

The supraorbital boss shape varies among burnetiamorphs.[1] Basal forms such as Lemurosaurus and Lobalopex have the primitive condition of having a single supraorbital boss.[1] Paraburnetia and Proburnetia have this variation.[1] Whereas Bullacephalus and Burnetia show the derived variation in which the supraorbital boss comprises two separate swellings and a valley between. [7] Paraburnetia lack the prominent anterior dorsal orbital depression in the fossa as seen in Bullacephalus, Burnetia, and Proburnetia.[1] The prominent 'knobs' that are supratemporal are created primarily by squamosal and parietal.[1] Unique among burnetiamorphs, the supratemporal 'knob' extends dorsally.[1] The Parietal foramen is thickened to crease a large swelling bump. [1]

Palate

The most notable and distinct characteristic of the palate is that the elongated palatine part of the palatinepterygoidis relative to Proburnetia. [1] In Bullacephalus, the pterygoid and palatine flare combined together is very wide. This is in contrast to the narrow flare shown by Burnetia and Proburnetia. [1] As shared by burnetia, labalopex, and proburnetia, paraburnetia lack teeth on the pterygoid that has expanded laterally. [1]

Lower Jaw

In lateral view, the lower jaw has a long, dentary that provides most of the lateral surface.[1] Near the coronoid, the dorsal rim swells and thickens, as in other biarmosuchians.[1] Four large incisiform teeth are present on either side of the lower jaw, while an additional small one is present adjacent to the midline.[1] This small incisiform is much shorter than the rest and appears to be a replacement tooth that is not yet fully erupted.[1] The coronoid element is a flat, triangular element, which differs from other biarmosuchians coronoid element shape.[1] Paraburnetia have large reflected lamina[1] and the angular has the same ridge structure as Lemurosaurus and Lobalopex.[7]

Biostratigraphic History

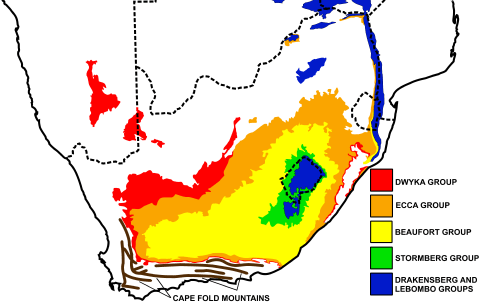

Burnetiamorph biostratigraphic overlap in Beaufort Group of South Africa is extremely rare.[11] The single event of overlap was the discovory of Lemurosaurus and Paraburnetia. The Beaufort Group is mudrock, with thick layers of multiculored siltstone underneath. [12] Floodplains are connected with rivers[1]. Although the Beaufort Group is now semi-desert, it has been hypothesized to have had forests historically and been cold since it was near the arctic in the time of Pangea.[12] The Beaufort group is known for dicynodontia fossils and there are many co-occurrences of burnetiamorphs found near other dicynodonts.[1]

The co-occurrence of the two burnetiamorphs appeared in the Cistecephalus Assemblage Zone.[1] In 1838, Andrew Geddes Bain was first to discover fossil reptiles in the Beaufort Zone.[13] The Beaufort Group has become famous for Permian and Triassic fossils found and has since been subdivided into sub-zones based on biostratigraphy.[13] The third zone, of six zones, suggested by Broom [14] being Cistecephalus Assemblage Zone.[1] Biarmosuchian fossils are rare, with only thirty specimens currently discovered.[11] Of 3,755 fossils found from the Cistecephalus AZ, only four are biarmosuchians.[11]

Due to the lack of stratigraphic co-occurrence, burnetiamorphs most likely have a wide distribution on Pangea.[1] Evidence of this wide distribution is supported by the findings in collecting areas in Russia and South Africa.[1] Despite burnetiid species occurrences being rare and discovered from different zones, the family was species-rich, with one specimen per genus, suggesting that they had high rates of speciation and extinction.[9]

Classification

Paraburnetia belongs to the clade burnetiidae, a subdivision of the greater clade biarmosuchian therapsids.[1][15] Biarmosuchians are typically considered the most basal major lineage of therapsids.[1] Biarmosuchia consists of a paraphyletic series of basal biarmosuchians that are fairly typical early therapsids, and the derived clade Burnetiamorpha, characterized by skulls ornamented by horns and bosses.[1]

The close morphological similarity between Paraburnetia and Proburnetia indicates that there was faunal interaction between their zones in early Wuchiapingian.[1] On the geological timescale, Wuchiapingian was a stage of the Permian. [16] Additionally, an analysis of the phylogenetic relationships showed that Burnetia, Bullacephalus, Niuksenitia, Paraburnetia, and Proburnetia are within clade Burnetiidae.[1] Within Burnetiidae, Proburnetia and Paraburnetia are sister taxa and Lemurosaurus is the most basal burnetiamorph.[1]

| Biarmosuchian |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology

Due to retrieving only the skull of the paraburnetia specimen and the other Burnetiidae, there is little information on their entire body morphology. However, knowledge of carnivorous traits and widespread dispersal of burnetiidae occurrences follows the pattern that carnivore species decrease in density near the edge of their ranges as a result of their environment resources not being able to support as many. [18] Therefore, burnetiamorphs populations for a given area were inevitably lower than for herbivores living in the same region.[19] This indicates that burnetiamorph species in the Karoo Basin were a result of the land being on the edge of their territory range, in which case same species should be found in adjacent regions, but not the same regions.[9]

Recent Discoveries and Implications

The new finding of sister taxa Lende chiweta indicates that Africa may have been a migration corridor between the southern and northern parts of Pangea during the late Permian. [20]

See Also

therapsid; Proburnetia; Biarmosuchus; burnetiidae;

Other Recreated Paraburnetia Images

Search "Parabernetia" in Diviant Art

References

- Smith, R.M.H.; Rubidge, B.S.; Sidor, C.A. (2006). "A new burnetiid (Therapsida: Biarmosuchia) from the Upper Permian of South Africa and its biogeographic implications". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 26 (2): 331–343. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2006)26[331:ANBTBF]2.0.CO;2.

- R. Broom 1923. On the structure of the skull in the carnivorous dinocephalian reptiles. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 2:661–684.

- Tatarinov, L. P. 1968. Novye teriodonty iz verknei Permi SSSR (New theriodonts from the Upper Permian of the USSR); pp. 32–46 in Verkhnepaleozoiskie i Mezsozoiskie zemnovodyne i presmykayushchiesya SSSR (Upper Paleozoic and Mesozoic Amphibians and Reptiles of the USSR), Nauka, Moscow. [Russian]

- Rubidge, B., & Sidor, C. (2001). Evolutionary patterns among Permo-Triassic therapsids. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 32, 449.

- Day Michael O., Ramezani Jahandar, Bowring Samuel A., Sadler Peter M., Erwin Douglas H., Abdala Fernando and Rubidge Bruce S. When and how did the terrestrial mid-Permian mass extinction occur? Evidence from the tetrapod record of the Karoo Basin, South Africa282Proc. R. Soc. B

- L. P. Tatarinov 1968. [New theriodonts from the Upper Permian of the USSR]. pp. 32–46 in [Upper Paleozoic and Mesozoic Amphibians and Reptiles of the USSR]. Nauka, Moscow. [Russian].

- Sidor, C. A., Hopson, J. A., & Keyser, A. W. (2004). A new burnetiamorph therapsid from the Teekloof Formation, Permian, of South Africa. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 24(4), 938-950.

- C. A. Sidor 2003. The naris and palate of Lycaenodon longiceps (Therapsida: Biarmosuchia), with comments on their early evolution in the Therapsida. Journal of Paleontology 77:153–160.

- Day, M. O., Smith, R. M., Benoit, J., Fernandez, V., & Rubidge, B. S. (2018). A new species of burnetiid (Therapsida, Burnetiamorpha) from the early Wuchiapingian of South Africa and implications for the evolutionary ecology of the family Burnetiidae. Papers in Palaeontology, 4(3), 453-475.

- Rubidge, B. S., & Sidor, C. A. (2002). On the cranial morphology of the basal therapsids Burnetia and Proburnetia (Therapsida: Burnetiidae). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 22(2), 257-267.

- Sidor, C. A. (2015). The first biarmosuchian from the upper Madumabisa Mudstone Formation (Luangwa Basin) of Zambia. Palaeontologia africana, 49, 1-7.

- Smith, R. M. H. 1987. Morphology and depositional history of exhumed Permian point-bars in the southwestern Karoo, South Africa. Journal Sedimentary Petrology 57:19–29.

- Rubidge, B. S. (1990). A new vertebrate biozone at the base of the Beaufort Group, Karoo Sequence (South Africa).

- BROOM, R. 1907. On some new fossil reptiles from the Karoo beds of the Victoria West, South Africa. Trans. S. Afr. Phil. Soc.,18: 31-42.

- Angielczyk, K. D., & Schmitz, L. (2014). Nocturnality in synapsids predates the origin of mammals by.

- Gradstein, F. M.; Ogg, J. G. & Smith, A. G.; 2004: A Geologic Time Scale 2004, Cambridge University Press

- Christian A. Sidor, James A. Hopson & André W. Keyser (2004) A new burnetiamorph therapsid from the Teekloof Formation, Permian, of South Africa, Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 24:4, 938-950, DOI: 10.1671/0272-4634(2004)024[0938:ANBTFT]2.0.CO;2

- BROWN, J. H. 1984. On the relationship between abundance and distribution of species. The American Naturalist, 124, 255–279

- P ET ERS, R. H. and WASS EN B ERG, K. 1983. The effect of body size on animal abundance. Oecologia, 60 (1), 89–96.

- Citation for this article: Kruger, A., B. S. Rubidge, F. Abdala, E. Gomani Chindebvu, and L. L. Jacobs. 2015. Lende chiweta, a new therapsid from Malawi, and its influence on burnetiamorph phylogeny and biogeography. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. DOI: 10.1080/02724634.2015.1008698.