Kʼinich Janaabʼ Pakal

Kʼinich Janaab Pakal I[N 1] (Mayan pronunciation: [kʼihniʧ xanaːɓ pakal]), also known as Pacal, Pacal the Great, 8 Ahau and Sun Shield (March 603 – August 683),[1] was ajaw of the Maya city-state of Palenque in the Late Classic period of pre-Columbian Mesoamerican chronology. He acceded to the throne in July 615 and ruled until his death. During a reign of 68 years—the fifth-longest verified regnal period of any sovereign monarch in history, the longest in world history for more than a millennium,[N 2] and still the second longest in the history of the Americas[N 3]—Pakal was responsible for the construction or extension of some of Palenque's most notable surviving inscriptions and monumental architecture.[N 4][2][3] Pakal is perhaps best-known in popular culture for his depiction on the carved lid of his sarcophagus, which has become the subject of pseudoarchaeological speculations.[4]

| Kʼinich Janaab Pakal I | |

|---|---|

| Ajaw of Palenque | |

Pacal the Great. | |

| Reign | July 615 – August 683 |

| Predecessor | Sak Kʼukʼ (his mother) |

| Successor | Kʼinich Kan Bahlam II |

| Regent | Sak Kʼukʼ (his mother) |

| Born | 9.8.9.13.0 — 21 March 603 |

| Died | 9.12.11.5.18 — 26 August 683 (aged 80) |

| Burial | |

| Spouse | Lady Tzʼakbu Ajaw |

| Issue | Kʼinich Kan Bahlam II Kʼinich Kʼan Joy Chitam II Tiwol Chan Mat? |

| Father | Kʼan Moʼ Hix |

| Mother | Sak Kʼukʼ |

| Religion | Maya religion |

Name

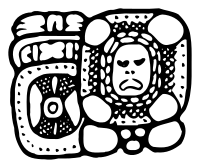

Before his name was securely deciphered from extant Maya inscriptions, this ruler had been known by an assortment of nicknames and approximations, including Pakal or Pacal, Sun Shield, 8 Ahau, and (familiarly) as Pacal the Great. The word pakal means "shield" in the Classic Maya language.[5]

In modern sources his name is also sometimes appended with a regnal number,[N 5] to distinguish him from other rulers with this name, that either preceded or followed him in the dynastic lineage of Palenque. Confusingly, he has at times been referred to as either "Pakal I" or "Pakal II". Reference to him as Pakal II alludes to his maternal grandfather (who died c.612) also being named Janahb Pakal. However, although his grandfather was a personage of ajaw ranking, he does not himself appear to have been a king. When instead the name Pakal I is used, this serves to distinguish him from two later known successors to the Palenque rulership, Kʼinich Janaab Pakal II (ruled c. 742) and Janaab Pakal III, the last-known Palenque ruler (ruled c.799).[6]

Early life

Kʼinich Janaab Pakal I was born on 9.8.9.13.0 - March 603. This was a particularly violent time in the history of Palenque; two years later, in 605, Palenque was attacked by the Mayan state of Kaan, and a new ruler was instated. Then again Kaan sacked Palenque when he was eight and nine (in 610 and 611). Pakal ascended the throne at age 12 and lived to the age of 80. He was preceded as ruler of Palenque by his mother, Lady Sak Kʼukʼ as the Palenque dynasty seems to have had Queens only when there was no eligible male heir; Sak Kʼukʼ transferred rulership to her son upon his official maturity.[7]

In 626 Pakal married Ix Tzʼakbu Ajaw who was born in Uxteʼkʼuh. Tzʼakbu Ajaw was a descendant of the Toktahn dynasty, the original dynasty of Palenque.

Reign

Pakal expanded Palenque's power in the western part of the Maya states and initiated a building program at his capital that produced some of Maya civilization's finest art and architecture.

In 628, one of Pakal's officials (aj kʼuhuun), was captured by Piedras Negras. Six days later Nuun Ujol Chaak, ajaw of Santa Elena, was captured and taken to Palenque. Santa Elena became a tributary of Palenque. Having been appointed ajaw at the age of twelve, Pakal's mother was a regent to him. Over the years she slowly ceded power until she died in September 640. In 659 Pakal captured six prisoners, One of them, Ahiin Chan Ahk, was from Pipaʼ, generally associated with Pomona. In 663 Pakal killed another lord of Pipaʼ. At this time he also captured six people from Santa Elena.[8]

In 647 Kʼinich Janaab Pakal began his first construction project (he was 44 at the time). The first project was a temple today called in Spanish El Olvidado (the Forgotten) because it's far away from Lakamhaʼ. Of all Pakal's construction projects, perhaps the most accomplished is the Palace of Palenque. The building was already in existence, but Pakal made it much larger than it was. Pakal started his construction by adding monument rooms onto the old level of the building. He then constructed Building E, called Sak Nuk Naah "White Skin House" in Classic Maya for its white coat of paint rather than the red used elsewhere in the palace. The east court of the palace is a ceremonial area marking military triumphs. Houses B and C were built in 661 and house A in 668. House A is covered with frescos of prisoners captured in 662.[9][10]

The monuments and text associated with Kʼinich Janaab Pakal I are: Oval Palace Tablet, Hieroglyphic Stairway, House C texts, Subterranean Thrones and Tableritos, Olvidado piers and sarcophagus texts.[11]

After his death, Pakal was deified and was said to communicate with his descendants. He was succeeded by his son, Kʼinich Kan Bahlam II.

Burial

Pakal was buried in a colossal sarcophagus in the largest of Palenque's stepped pyramid structures, the building called Bʼolon Yej Teʼ Naah "House of the Nine Sharpened Spears"[12] in Classic Maya and now known as the Temple of the Inscriptions. Though Palenque had been examined by archaeologists before, the secret to opening his tomb — closed off by a stone slab with stone plugs in the holes, which had until then escaped the attention of archaeologists—was discovered by Mexican archaeologist Alberto Ruz Lhuillier in 1948. It took four years to clear the rubble from the stairway leading down to Pakal's tomb, but it was finally uncovered in 1952.[13] His skeletal remains were still lying in his coffin, wearing a jade mask and bead necklaces, surrounded by sculptures and stucco reliefs depicting the ruler's transition to divinity and figures from Maya mythology. Traces of pigment show that these were once colorfully painted, common of much Maya sculpture at the time.[14]

Whether the bones in the tomb are really those of Pakal is under debate because analysis of the wear on the skeleton's teeth places the age of the owner at death as 40 years younger than Pakal would have been at his death. Epigraphers insist that the inscriptions on the tomb indicate that it is indeed Kʼinich Janaabʼ Pakal entombed within, and that he died at the age of 80 after ruling for around 70 years. Some contest that the glyphs refer to two people with the same name or that an unusual method for recording time was used, but other experts in the field say that allowing for such possibilities would go against everything else that is known about the Maya calendar and records of events. The most commonly accepted explanation for the irregularity is that Pakal, being an aristocrat, had access to softer, less abrasive food than the average person so that his teeth naturally acquired less wear.[15]

An underground water tunnel was found under the Temple of Inscriptions in 2016. Later on, a mask of Pakal was discovered in August 2018.[16][17]

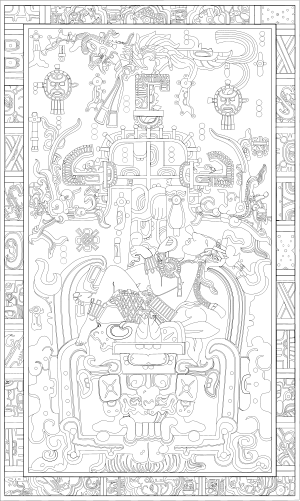

Iconography of Pakal's sarcophagus lid

The large carved stone sarcophagus lid in the Temple of Inscriptions is a unique piece of Classic Maya art. Iconographically, however, it is closely related to the large wall panels of the temples of the Cross and the Foliated Cross centered on world trees. Around the edges of the lid is a band with cosmological signs, including those for sun, moon, and star, as well as the heads of six named noblemen of varying rank.[18] The central image is that of a cruciform world tree. Beneath Pakal is one of the heads of a celestial two-headed serpent viewed frontally. Both the king and the serpent head on which he seems to rest are framed by the open jaws of a funerary serpent, a common iconographic device for signalling entrance into, or residence in, the realm(s) of the dead. The king himself wears the attributes of the Tonsured maize god - in particular a turtle ornament on the breast - and is shown in a peculiar posture that may denote rebirth.[19] Interpretation of the lid has raised controversy. Linda Schele saw Pakal falling down the Milky Way into the southern horizon.[20]

Pseudoarchaeology

Pakal's tomb has been the subject of ancient astronaut hypotheses since its appearance in Erich von Däniken's 1968 best-seller Chariots of the Gods? Von Däniken reproduced a drawing of the sarcophagus lid, incorrectly labeling it as being from "Copán" and comparing Pacal's pose to that of Project Mercury astronauts in the 1960s. Von Däniken interprets drawings underneath him as rockets, and offers it as possible evidence of an extraterrestrial influence on the ancient Maya.[21]

In the center of that frame is a man sitting, bending forward. He has a mask on his nose, he uses his two hands to manipulate some controls, and the heel of his left foot is on a kind of pedal with different adjustments. The rear portion is separated from him; he is sitting on a complicated chair, and outside of this whole frame, you see a little flame like an exhaust.[22]

Another example of this carving's manifestation in pseudoarchaeology is the identification by José Argüelles of "Pacal Votan" as an incarnation named "Valum Votan," who would act as a "closer of the cycle" in 2012 (an event that is also significant on Argüelles' "13 Moon" calendar). Daniel Pinchbeck, in his book 2012: The Return of Quetzalcoatl (2006), also uses the name "Votan" in reference to Pakal.

Notes

- The ruler's name, when transcribed is KʼINICH-JANA꞉B-PAKAL-la, translated "Radiant ? Shield", Martin & Grube 2008, p. 162.

- Pakal's record was eventually surpassed in June 1711, by Louis XIV of France; Louis's record still stands as of today.

- Pakal's record was eventually surpassed in March 2020, by Elizabeth II as monarch of Canada; Elizabeth's record still stands as of today.

- These are the dates indicated on the Maya inscriptions in Mesoamerican Long Count calendar. Born: 9.8.9.13.0 8 Ahaw 13 Pop; acceded: 9.9.2.4.8 5 Lamat 1 Mol; died: 9.12.11.5.18 6 Etzʼnab 11 Yax, Martin & Grube 2008, p. 162.

- Maya rulership titles and name glyphs themselves do not use regnal numbers, they are a convenience only of modern scholars.

Footnotes

- 9.8.9.13.0 and 9.12.11.5.18 (Tiesler & Cucina 2004, p. 40)

- Skidmore 2010, p. 71.

- Martin & Grube 2008, pp. 162-168.

- Wade, Lizzie (2019-04-09). "Believe in Atlantis? These archaeologists want to win you back to science". Science | AAAS. Retrieved 2019-04-14.

- Skidmore 2010, pp. 71-73.

- Skidmore 2010, pp. 56-57, pp. 71-73, p. 83, p. 91.

- Martin & Grube 2008, pp. 162-165.

- Skidmore 2010, pp. 71-73.

- Martin & Grube 2008, pp. 162-168.

- Skidmore 2010, pp. 71-73.

- Martin & Grube 2008, p. 162.

- Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico

- Mathews, p. 1.

- Stokstad, p. 388.

- Mathews, p. 1.

- "Incredible Maya discovery: Ancient king's mask uncovered in Mexico". Fox News. 29 August 2018.

- "This Haunting Mask Could Be The Face of The Longest-Reigning Ancient Maya King". Science Alert. 30 August 2018.

- Schele & Mathews 1998, pp. 111-112.

- Stuart & Stuart 2008, pp. 174-177

- Freidel, Schele & Parker 1993, pp. 76-77

- Finley, p.1

- von Däniken, pp. 100-101, line drawing between pp. 78-79.

References

- Finley, Michael. "Von Daniken's Maya Astronaut". SHAW WEBSPACE. Archived from the original on April 12, 2008. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- Freidel, David A.; Schele, Linda; Parker, Joy (1993). Maya Cosmos: Three Thousand Years on the Shaman's Path. New York: William Morrow and Company. ISBN 9780688100810.

- Martin, Simon; Nikolai Grube (2008). Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens: Deciphering the Dynasties of the Ancient Maya (2nd ed.). London and New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 9780500287262. OCLC 191753193.

- Mathews, Peter. "WHO'S WHO IN THE CLASSIC MAYA WORLD". Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, Inc. (FAMSI). Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- Schele, Linda; Mathews, Peter (1998). The Code of Kings: The Language of Seven Sacred Maya Temples and Tombs. New York: Touchstone. ISBN 068480106X. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- Skidmore, Joel (2010). The Rulers of Palenque (PDF) (Fifth ed.). Mesoweb Publications. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- Stokstad, Marilyn (2008). Art History Fourth Edition. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-205-74422-0.

- Stuart, David; Stuart, George (2008). Palenque: Eternal City of the Maya. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 9780500051566.

- Tiesler, V.; Cucina, A.; Pacheco, A. Romano (2004-10-18). "Who was the Red Queen? Identity of the female Maya dignitary from the sarcophagus tomb of Temple XIII, Palenque, Mexico". HOMO. 55 (1): 65–76. doi:10.1016/j.jchb.2004.01.003. ISSN 0018-442X. PMID 15553269.

- von Däniken, Erich (1969). Chariots of the Gods?: Unsolved Mysteries of the Past. Bantam Books. ISBN 0285502565.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to K'inich Janaab' Pakal I. |

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Sak Kʼukʼ |

King of Palenque July 26, 615 – August 28, 683 |

Succeeded by Kʼinich Kan Bahlam II |

.jpg)