Paha (landform)

Paha (or greda) are elongated landforms composed either of only loess or till capped by loess.[1] In Iowa, paha are prominent hills that are oriented from northwest to southeast, formed during the period of mass erosion that developed the Iowan surface, and they are considered erosional remnants since they often preserve buried soils. Paha generally rise above the surrounding landscape more than 6.1 metres (20 ft).[2] The word paha means hill in Dakota Sioux.[3] Well known pahas include the hill on which the town of Mount Vernon, Iowa developed, Casey's Paha in Tama County, Iowa, and the Kirkwood Paha, home of Kirkwood Community College's campus.[3] These features are found in other regions of the United States and in Europe, where they are known as greda.

Formation

Pahas were formed during the last glacial stage. In North America this was the Wisconsinan. Pahas in Iowa contain thick deposits of Wisconsinan-aged Peoria Formation loess and the Farmdale Paleosol.[4] and they are also predominately found downwind of river valleys carrying Wisconsian outwash, i.e. sources of eolian sediment.[5] Landscapes that contain paha have a subdued, rolling topography that is thought to be caused due to periglacial erosion.[3] Some of this erosion could have been caused by snow melt niviation.[6] The gentle topography served as a surface for eolian sediment to travel across the area, similar to the Nebraska Sandhills. Saltating sand deflated loess on the uplands where not blocked upwind by a topographic barrier such as steep-walled stream valleys or vertical bedrock outcrops.[7] As a consequence, paha are found where downwind of impediments that protected loess deposit from saltating sand.[8] As paha grew, the rise in elevation due to loess aggregation would have altered local wind patterns by causing eddies in the hill's wake reducing the wind's effective strength.[9] Downwind of a forming paha, less sand would have been carried or mobilized, resulting in more loess. This pattern is seen in the linear relationship of multiple pahas downwind from a single topographic barrier.[5] In Iowa, the rapid accumulation of loess and erosion of the landscape is thought to have been partly synchronous during the Late Wisconsinan;[8] after the climate warmed and outwash shut off when glaciers retreated from the basin, the landscape overall stabilized.[10]

Modern Expression

Distribution

United States

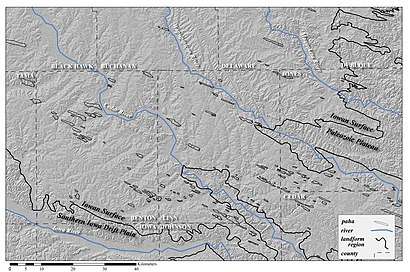

A well-defined band of pahas runs between Mount Vernon and Martelle, Iowa and is crossed by Iowa Highway 1. Most are in Benton, Linn, Johnson and Jones counties.

Casey's Paha State Preserve in Hickory Hills County Park, Tama County, Iowa preserves the southeast end of a 2-mile (3.2 km) long paha.[12]

Paha ridges have also been identified in Kansas[13] and in western Illinois.[14][7]

Similar ridge forms occur in the arid upwind parts of the Palouse region of Washington.[15] Outside of the Midwest, several of the above-cited authors use the term greda to refer to features that are indistinguishable from paha ridges.

Europe

Ridges, similar to the pahas of Iowa, are found in Europe, where they are known as greda. In Heidelberg, Germany, for example, they form NNW-ESE aligned ridges on a bank on the River Rhine[16] and have been dated to between 40,000 and 34,000 years old.[17]

References

- McGee, W J, 1853-1912. (1891). The Pleistocene history of northeastern Iowa. Gov't. Print. Off. OCLC 884016785.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Paha Ridge Landform Features of Iowa, Iowa Geological Survey, 2006. Accessed 2008-08-12.

- Landforms of Iowa by Jean C. Prior, University of Iowa Press, Iowa City, 1991

- Ruhe, Robert; Dietz, W.P.; Fenton, Tom; Hall, Hall (1968). "Iowan Drift Problem". Iowa Geological Survey Report of Investigations. 7: 40 p.

- Kerr, Phillip; Tassier-Surine, Stephanie; Kohrt, Casey (2019). "Trends in eolian features on the Iowan Erosion Surface". Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs. 51–2. doi:10.1130/abs/2019SC-326991 – via Geological Society of America.

- Iannicelli, Michael (2010). "Evolution of the Driftless Area and Contiguous Regions of Midwestern USA Through Pleistocene Periglacial Processes". The Open Geology Journal. 4 (1): 35–54. Bibcode:2010OGJ.....4...35I. doi:10.2174/1874262901004010035.

- Mason, Joseph A.; Nater, Edward A.; Zanner, C. William; Bell, James C. (1999). "A new model of topographic effects on the distribution of loess". Geomorphology. 28 (3–4): 223–236. Bibcode:1999Geomo..28..223M. doi:10.1016/S0169-555X(98)00112-3.

- Mason, Joseph (2015). "Up in the refrigerator: geomorphic response to periglacial environments in the Upper Mississippi River basin, USA". Geomorphology. 248: 363–381. doi:10.1016/j.geomorph.2015.08.004.

- Kok, Jasper F. Parteli, Eric J. R. Michaels, Timothy I. Bou Karam, Diana (2012). "The physics of wind-blown sand and dust". Reports on Progress in Physics. Physical Society (Great Britain). 75 (10): 106901. arXiv:1201.4353. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/75/10/106901. OCLC 875178143. PMID 22982806.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Ruhe, Robert (1969). "Quaternary Landscapes in Iowa". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Leichty, Reid (2008). "Pre-Settlement Vegetation at Casey's Paha State Preserve, Iowa". Iowa Academy of Science. 115: 12–16 – via Journal of the Iowa Academy of Science.

- Black Hawk County, 2008-2012 Resource Enhancement and Protection Plan, July 31, 2007, p. 6

- Kay, George F. (1917), Iowa Geological Survey, Volume 26, pp. 150–152

- Iannicelli, Michael (2003). "Devon Island's Oriented Landforms as an Analog to Illinois-Type Paha". Polar Geography. 27 (4): 339–350. doi:10.1080/789610227.

- David R. Gaylord, Geomorphic Development of a Late Quaternary Paired Eolian Sequence, Columbia Plateau, Washington, Geological Society of America 2002 Annual Meeting, Denver.

- Rousseau, D-D.; Derbyshire, E.; Antoine, P.; Hatté, C. (2018). "European Loess Records". Reference Module in Earth Systems and Environmental Sciences. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-409548-9.11136-4.

- Knippertz, P. and Stuut, J-B.W. (editors) (2014). Mineral Dust: A Key Player in the Earth System. Springer. p. 419. ISBN 978-94-017-8977-6.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)